Dominic Johnson’s recent book, The Art of Living, is subtitled “an oral history of performance art”. It includes 12 in-depth interviews with figures who “exert massive influence upon peers and younger artists”, many of them for pretty “extreme” work. One man “becomes a Goddess, a silhouette, and a channel for the passage of dead legends, less a shaman than a creature of the night. Another turns his asshole into a tribute, temple, target, totem and tomb. An artist slathers her husband in food, and feeds him through a tube, after secreting him in bondage in the darkest basement of her love.”

Johnson – senior lecturer in drama at Queen Mary University of London – is explicit that he has chosen artists who he thinks are important but who have been rather neglected within the “standard history of performance art”. On the face of it, therefore, one might have expected his interviewees to be pleased that they were included. The book gives them recognition, lets them explain their work on their own terms and might even lead to fresh commissions. Yet several seem suspicious and almost irritated by academic attention.

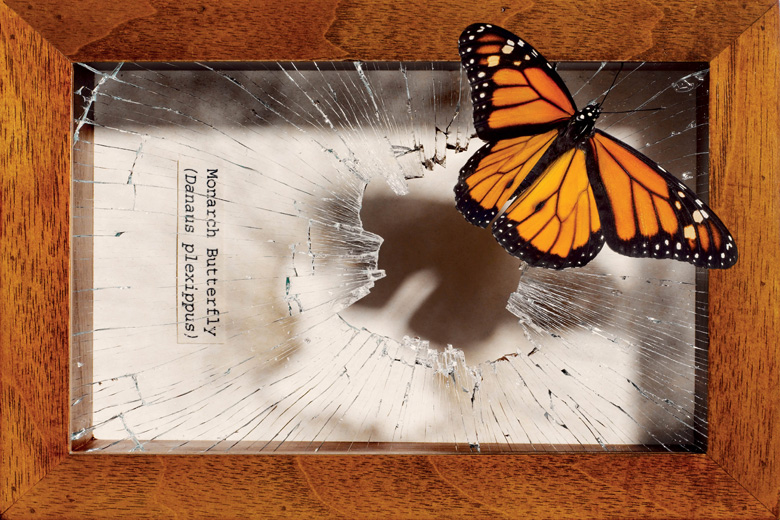

“Interpretation is always the last word,” says one interviewee, known as Ulay. “I want to remain difficult to capture – and art history is an instrument of intellectual capture.” Anne Bean, reports Johnson, “refused to allow her work to be documented for several decades, and disengaged from the critical reception of art, leaving her work to percolate, untouched and unmarred by scholarly custodianship, with the ambition of not ‘being part of an art-historical way of seeing’”. Perhaps, he reflects, there is something about “the attention of scholars” that brings a “sense of containment or predation” that these artists find uncomfortable.

Unlike obscure performance artists, many of those who produce “mainstream” novels and films attract reactions from ordinary punters, newspapers reviewers and academic critics. The first category have paid their money and can obviously say what they want (although film directors sometimes report how strange it is to work intensively on a project for two years and then get comments along the lines of “How did you get that dog to run uphill so fast?” or “Wouldn’t that actress have looked better in a blue dress?”). Many people claim not to read reviews of their work in the national press, although these can clearly have a direct impact on book and ticket sales. Academic articles and monographs seldom matter in the same way.

So what is it like for creative writers and artists to be “captured” or “contained” in the academic spotlight? Do they seek out such criticism or make a point of avoiding it? Academic criticism is sometimes attacked or mocked for being overingenious or insufficiently aware of the concrete realities of creative work, not to mention the financial and logistical constraints of media such as the cinema. But is it sometimes also useful for creative people to read the results of academics’ serious critical engagement with their output?

Interviewed by Times Higher Education last year, author David Lodge was very clear that reading academic commentary on his novels made him uneasy: “Although I wrote academic criticism myself and taught other people how to write it, it’s always trying to exert and exhibit a kind of professional mastery over the subject, whether it’s critical or laudatory. Though I was grateful for the attention and the implied value it gives to [my work], it’s a slightly uncomfortable feeling when that kind of grid of interpretation is put over [it]…If I disagree with it, even if it’s complimentary, it irritates or distracts me or affects what I am trying to write now. If I read it, I’ve got to give an opinion about it, but I don’t want to do that. Giving a view on whether it’s right or not about my work is fatal [to the creative process].”

The novelist and critic Marina Warner agrees that reading about her own work is “very strange” and makes her “extremely self-conscious”. She recalls being taken to task, on one occasion, for “being a soft feminist” and “insufficiently condemning” in a story describing a rape. On a visit to Egypt, she was strongly criticised by a professor for “colonial” attitudes in her novel Indigo, although she was “flattered he had read it so seriously”. Rather less convincing was the academic who suggested that the title contained the hidden key to the book, through an oblique reference to her grandfather, the cricketer Pelham “Plum” Warner.

Tom Phillips has worked in a variety of different media and is perhaps best known for A Humument, created from a long-forgotten Victorian novel he picked up for three pence and then transformed into a completely different narrative using collage, cut-ups and other techniques. As a young artist, he recalls, he was “always glad of a mention” in newspapers and magazines, yet “the idea of academic attention was worlds away”.

“It was not until 1985 in Rouen at a conference devoted to my work…that I collided with its paradoxes and mysteries. Hardcore structuralism had evidently sought shelter in the provinces. Several speakers had found my work a suitable case for treatment. My French is good and I anticipated no difficulty in following what was said. In one sense, that was true. Apart from a few fashionable critical terms, all was clear: yet I could not understand what the speakers were actually saying or follow the strange routes they took from what concerned my work into territories where they were at home.

“How can this be? I kept thinking. They are talking about the one thing I understand best, yet I do not recognise the kind of engagement they have made with it.”

As time went by, however, Phillips got used to “these technical and exegetic riffs” and is gratified that “much academic commentary turns out to be on my side…I must remember, however, that it is not for me but about me that they are writing. I should not complain, therefore, if the doors [commentary] might open for others are those I have passed through and shut behind me.”

Poet Fiona Sampson has an academic role herself as professor of poetry (and director of the Poetry Centre) at the University of Roehampton. In principle, she says, she doesn’t “vastly mind being misinterpreted by an academic or any other reader: that seems to me to be part of letting a work go – providing, of course, that their misinterpretation is professional and commonsensical enough to search the poem or book for what I am doing before it sounds off about what I am not.”

In reading academic responses to creative writing, Sampson is often reminded of two “brilliant, rather profound novels”: Patricia Duncker’s Hallucinating Foucault and Michael Frayn’s The Trick of It. The former depicts academic research as “passionate, dedicated reading: a form of love”, while the latter savages it as “destructive appropriation, envy, jealousy, failure to understand”. Although she believes that both contain an element of truth, Sampson is struck by the way that much academic criticism is “interested primarily in literary works (which they call ‘texts’, using the same word for all kinds of published and unpublished writing) as samples; so if your ‘text’ can be said to do something odd, however badly, that’s read as more interesting or culturally significant than something familiar done well”.

“Academics are, broadly speaking, competing with each other: it’s the virtuosity in their own terms, of what they have to say, that they care about, which is precisely why our writing is often merely co-opted by them to illustrate an argument they are making.” For the writer being analysed, in Sampson’s view, the result can “feel completely random”.

Iain Pears, probably best known for the elaborate narrative structures of novels such as An Instance of the Fingerpost and The Dream of Scipio, is married to an academic and lives among academics. He describes them as “by far the best (and increasingly the only) group of people who can engage with an entire text, and comment on its overall structure”. While professional editors at publishing houses are less and less willing or able to say that some characters are too bland or that a book needs radical cutting, “academics have no such qualms and are often very generous with their time”.

Since he largely writes novels set in the past, Pears has received less attention from literary scholars than from historians, historians of science and theologians, whom he regards as “less jargony and less judgemental”. As someone who occupies “a sort of netherworld in between different genres”, he thinks it unlikely that he will ever become “thesis fodder”, although he would have no objection: “While being placed into some small backwater of the literary canon might be uncomfortable, at least I will be fairly certain that the people placing me there will have actually read the books – which is not always the case with reviewers.” What remains odd, however, is to “discover I have been influenced by books or films I have never read, seen or even heard of (the comparison of Fingerpost to [the Japanese film] Rashomon being the most obvious example)”.

A. S. Byatt is very impressed that fellow novelist Toni Morrison apparently has “a shelf in her office with all the academic theses on her work efficiently arranged”. She is herself “full of good will” towards those who produce academic accounts of her work, but, in practice, finds them very difficult to read. She recalls an article about one of her stories that she thought was “brilliant” in the way that it picked up on her imagery and wove it all together – even though she had not had any of the thoughts that the writer described. Yet she adds that she wouldn’t want to read such articles too often.

Looking back to the start of his career, novelist Julian Barnes remembers that he was “keen, not to say obsessed, about reading every last scrap, positive or negative, about my books. I kept an enormous scrapbook. If, at this early stage, anyone had written a book about me, I would have consumed it avidly.”

Yet he soon began to realise that “nothing anyone said about me would have the slightest effect on what I wrote in the future” and that he had “a great antipathy for seeing my novels as interconnected (let alone connected to the general stream of English fiction). This is/was naive, of course, but it’s a necessary naivety. In order to make the thing what it is, you have to pretend that it is isolated from everything except the world which is its subject and the reader who will be its object. So thinking that This Book connects in some way to That Book is a distraction. Say the word oeuvre to me and I reach for my gun.”

After publishing about four novels, Barnes “met a very intelligent and charming French postgraduate. She was completing a thesis on my work up till then, and said she would send it to me. I said I was afraid I wouldn’t read it. She said that was fine. She has since written three, perhaps four, books about me, none of which I have read. This is quite understood between us, and we are firm friends – perhaps firmer than if I had read her books.”

When it comes to applying critical theory to his work, Barnes has “occasionally glanced at theoretical – Lacanian, Derridean – articles about what I write, always with a kind of head-shaking bafflement. Of course they have nothing to do with what I write…Flaubert’s Parrot was once described as ‘a subtle riposte to Derrida’. I thought this was hilarious. As if you go into your study in the morning, sit at your typewriter and think, ‘Well, what will it be today? Shall I have a little laugh at Lacan? No – I’ve got it – a subtle riposte to Derrida!’”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Critical matters?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?