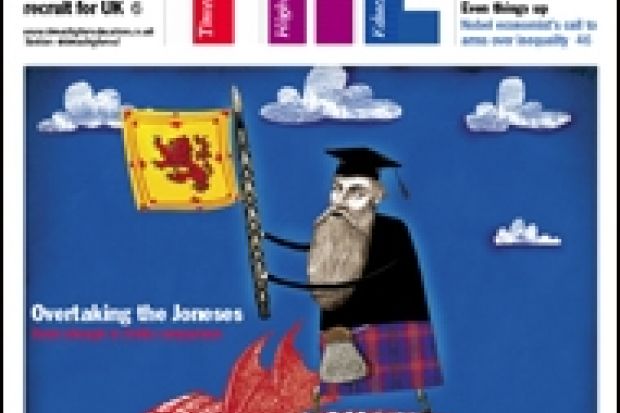

“There are no, none, zip, zero Welsh universities in the world top 200 Times Higher Education rankings,” bemoaned Angela Burns, the Welsh Conservative shadow minister for education, during a recent debate. “And that matters. Scotland is just over twice our size. We have zero. They have five.”

Although league table rankings are far from being the only measure of success, Burns is not the only Welsh person to have looked wistfully northwards and wondered: is Scotland doing better than us? And if so, why?

On measures of funding and research performance, Scotland appears to be ahead. When its vice-chancellors lie back and sun themselves on holiday this summer, they may well reflect on a job well done.

Persistent lobbying won them a funding settlement to 2014-15 that should help them keep up with their English counterparts when the latter start charging tuition fees of up to £9,000 a year. The numbers applying to start university in Scotland this autumn have held up better than they have in the rest of the UK, and the threat of an unwanted merger has been seen off.

The Welsh sector, in contrast, has been told that it is failing to reach its potential. In June last year, the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales reaffirmed the oft-made case for consolidating the country’s 10 institutions into six, and most of its proposals have been endorsed by the government in Cardiff. Welsh universities do not win enough research money and have trouble maintaining a broad subject range, HEFCW said.

The country’s academy has also suffered a year of unpleasant headlines: the University of Wales, once a source of national pride for many, has in effect been scrapped following a visa scam at a linked college; relations with the Welsh government are frosty to say the least; and applications to its institutions have dropped further than anywhere else in the UK.

But is it fair - or even possible - to compare the two systems? Is Wales really underachieving? And is one Celtic nation better prepared than the other for the challenges on the horizon?

Because it has a significantly smaller population and economy, it would be unfair to expect Wales to match Scotland’s higher education system pound for pound (or university for university).

Using the measure of gross value added (similar to gross domestic product, but minus taxes and including subsidies on products), Wales’ output is less than half the size of Scotland’s.

Still, there are other discrepancies that cannot be explained away by raw scale - for example, funding per student. Over the past decade, Wales has had the lowest teaching income per student of all the home nations (except in 2005-06, when Northern Ireland was marginally lower), according to Universities and Constitutional Change in the UK, a recent report by the Higher Education Policy Institute into the impact of devolution on higher education.

“It’s not a surprise that Welsh higher education is poorly funded,” says Alan Trench, honorary senior research fellow at University College London’s Constitution Unit. “Wales, generally, is underfunded. The evidence is pretty clear.”

The Barnett formula, which determines the amount of money given to devolved governments, is not based on need but rather on a negotiated proportion of certain types of English funding, he explains. Scotland has over the years been able to negotiate a better deal from Westminster than Wales.

Amid debate about the need for mergers, how do Welsh and Scottish institutions compare in size? Since the 1980s there has been a view in Wales that its institutions are too small and as a result fail to achieve the critical mass needed to win research grants, the Hepi report says.

Yet institutions in Wales are no smaller on average than those in Scotland. In terms of average student numbers, Welsh universities (11,626) are fractionally smaller than Scottish ones (11,6), although institutions in both nations are substantially smaller than the English average (15,982). Three universities in Wales, and four in Scotland, have fewer than 10,000 higher education students.

In light of the destabilising impact of England’s new funding system, those arguing for mergers stress that consolidation is needed to make institutions financially resilient by combining their balance sheets.

“In England you can have a debate about letting institutions fail, as the present government does,” explains Phil Gummett, chief executive of HEFCW. But in a sector “the scale of Wales, you can’t afford to have any institution fail. You have to find a way to manage change.”

Welsh institutions do indeed have less of a cash cushion to protect them from any shock waves caused by the big bang of marketised competition being introduced in England.

According to Finances of Higher Education Institutions, a report by the Higher Education Statistics Agency published in May, Scottish institutions racked up a 3.7 per cent budget surplus in 2010-11 compared with a Welsh average of 2.5 per cent (although Welsh institutions had been doing better in the previous two years). Again, both countries lagged behind England.

Scotland also brings in far more research money, winning more than four times as much from the UK research councils and industry in 2009-10 as Wales. It also did better in the 2008 research assessment exercise.

But the picture is not so clear cut if you consider that Wales is stronger in the arts and humanities than it is in medical research - where Scotland is particularly successful - and the former is simply cheaper to fund than the latter, Gummett says.

In politics, too, there are marked discrepancies between the Celtic countries. In its report on devolution, Hepi describes the relationship between the Welsh higher education sector and the Cardiff government as “chequered”. Leighton Andrews, the Welsh education minister, is known for his tough talk on reform. He has called for the sector to “adapt or die” and has threatened to use his legal powers to force through mergers in the face of objections from the board of governors at Cardiff Metropolitan University. This is “not really the sort of ministerial language you’d expect in higher education”, Tony Bruce, former director of policy development at Universities UK and author of the Hepi report, has said.

Such poor relations can have serious consequences. The continuing stalemate over the merger issue and concerns about performance may explain why the Welsh government has not been prepared to close the funding gap with England, Hepi’s report suggests.

“I’m not going to tell you we have a cosy relationship with government - that’s not the kind of relationship you need,” argues Amanda Wilkinson, director of Higher Education Wales, a national council of UUK and the body that represents the interests of Welsh institutions. “But we have a good relationship, [which is] constructive.”

North of the border, public spats have been rarer. Vice-chancellors in Scotland were given a £58 million Christmas present in the form of a boost to their teaching grant that put to bed, at least for now, worries of a funding gulf emerging between Scotland and England as a result of the latter’s new fees regime.

Scottish universities “have done really very well”, says Trench. “If you’re not going to go down the tuition-fees path, competing with England is going to be pretty damn tough. They did a damn good job.”

This marks something of a political comeback for Scottish universities, which suffered “exceptionally badly” in the 2007 Budget following the Scottish National Party’s election success in Holyrood, Trench believes.

The Scottish academy did have a brush with the kind of enforced merger being considered in Wales when, last September, the Scottish Funding Council wrote to the University of Dundee and the University of Abertay Dundee asking them to consider merging.

But after a hostile response from both institutions, the SFC issued a statement saying that the merger was not in prospect.

“The [Holyrood] government will never try that again,” predicts Ferdinand von Prondzynski, principal of Robert Gordon University.

To what extent does the age of institutions affect their success? Scotland’s academy has, of course, a 400-year head start on that of Wales. Four of Scotland’s top five THE-ranked institutions - the University of Edinburgh (founded in 1582), the University of St Andrews (1413), the University of Glasgow (1451) and the University of Aberdeen (1495) - are older than all other UK institutions bar the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. As a mark of their antiquity, the 15th-century universities do not rely on royal charters but papal bulls.

Wales entered the fray only in 1822 with the opening of what became the University of Wales, Lampeter. In 2009, the institution merged with Trinity University College to become the University of Wales Trinity Saint David; Trinity Saint David is now expected to merge with Swansea Metropolitan University and the University of Wales.

Age can have an impact on ranking positions, says Roger Brown, professor of higher education policy at Liverpool Hope University, because a high-ranking position “usually correlates quite well with income per student and the length of time an institution has had its own degree-awarding powers”.

“Not surprisingly, the elite universities tend to be old,” wrote Jamil Salmi, former tertiary education coordinator at the World Bank, in an analysis for the recent THE 100 Under 50 rankings. But, he went on to say, there are examples of universities that have “achieved national and even global pre-eminence in a few decades, sometimes fewer than three”, as a result of their having the right “financial mechanisms; strong governance; and a concentration of talent”.

Meanwhile, Scotland maintains a healthy culture of respect for the university that is perhaps weaker in England or Wales, Gummett suggests. During Scotland’s 18th-century Enlightenment, new thought was often incubated in universities that were already hundreds of years old. “If you walk up the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, there’s [a statue of] David Hume on one side and Adam Smith on the other”, he says.

While it is clear that many of Scotland’s universities are elite, they have also been criticised for being too exclusive. Last month, the National Union of Students highlighted statistics showing that in 2010-11 just 2.7 per cent of Scottish entrants (13 students) to St Andrews hailed from the country’s least affluent 20 per cent of postcode districts. The proportions at Aberdeen (3.1 per cent) and Edinburgh (5 per cent) were not hugely better.

The representative body Universities Scotland says that the institutions are improving their outreach work, and that a big gap in examination attainment has made it difficult to recruit the poorest students. Holyrood is currently looking to introduce fines for universities that do not hit targets on access.

Wales does better than Scotland in this respect, with a higher proportion of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Both Scotland and Wales face uncertainty as England introduces higher tuition fees, Hepi argues in its recent report.

If English students turn their backs on either country, their financial plans could be vulnerable. The proportion of students from England studying in Wales (41.4 per cent) is much higher than in Scotland (13.6 per cent), making the Welsh sector more exposed to fluctuations in demand.

Both the Cardiff and Edinburgh administrations hope that the flow of students between the home nations will remain roughly the same.

Statistics released in January by the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service show a big drop in English applicants to Welsh universities (12.3 per cent). Despite fears that the longer - and therefore more costly - Scottish four-year degree would put English students off in the age of higher fees, the number of applicants from south of the border declined by just 5.6 per cent, less than for England.

Regardless of student number flows, and despite the settlement achieved by Scottish vice-chancellors, the move from a teaching grant model to tuition fees in England could hit both Scotland and Wales in the pocket. Fee income, unlike funding council grant, is not a type of spending taken into account by the Barnett formula, so the devolved nations will get less as direct funding is cut, the Hepi report explains.

Then there is the question of independence. As the SNP gears up for a referendum on the issue in 2014, it may be treating the sector with kid gloves, says Gummett.

“It’s very important not to underestimate the concern among the SNP not to upset anyone [before 2014],” he says, his implication being that after that date, mergers and cuts could return to the agenda with a vengeance.

And if Scotland decides to break free of the UK, this could cost the country’s research. Independence would probably mean that Scotland could no longer access the coffers of Research Councils UK, from which it currently draws a disproportionately large amount of money, says Trench.

If Scotland were getting more out of a post-independence research council system than it was putting in, why would England, Wales and Northern Ireland allow it continuing access to the funds?

By 2014-15, Scotland expects to be bringing in £55 million a year from tuition fees from rest-of-UK students. If it chooses independence and becomes another member of the European Union, however, English students would become just another type of EU entrant. As a result, it seems likely that Scottish universities would have to charge them the same price as Scots - meaning either a loss of income or the politically unpalatable solution of raising fees for everyone. On the other hand, independence would give Scotland full tax-raising powers that it could use to invest more in its academy.

Whither Wales? Despite the public bickering of the past year, Wilkinson says that Welsh universities are broadly behind the merger agenda set out by HEFCW. And plans to reconfigure the sector are “not about fixing problems, but [rather] making sure that our higher education system is as good as it can be”, she argues.

“There’s a lot of cross-party support for the universities. I think everyone’s working in the same direction.” Whether the reforms will end unflattering comparisons with Scotland is another matter.