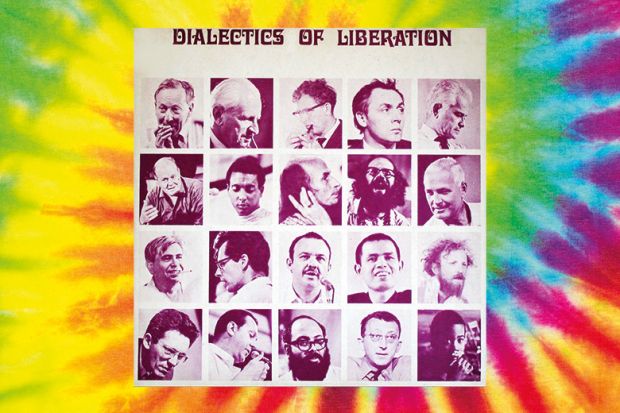

The 50th anniversary commemorations of 1967’s so-called Summer of Love have focused largely on the release of the Beatles’ seminal Sgt Pepper’s album and the legalisation of male homosexuality in the UK. However, no less historic – at least in academic circles – was the Congress on the Dialectics of Liberation (for the Demystification of Violence).

This extraordinary event – the very antithesis of the typically staid, regimented academic conference – took place at London’s Roundhouse during the final two weeks of July. Announcing itself as a “unique gathering to demystify human violence in all its forms, the social systems from which it emanates, and to explore new forms of action”, it emerged out of two intimately related and characteristically 1960s themes: existential psychiatry and the free universities movement. Both were liberationist, argumentative and radical to the core; the first was devoted to the emancipation of people with a mental illness and their psychiatric carers, the second to the liberation of students and teachers.

The organisers of the congress – four existential psychiatrists – aimed to educate and to set free. They would use the event to push forward their psychiatric interests and also to provide a model for how an academic conference should be conducted. Of course, so-called radical conferences were two a penny in the 1960s, as they still are today. But this one was on another level in every sense of the phrase.

First, there was the glamour of the organisers. Although Joe Berke and Leon Redler, both young Americans, did the bulk of the donkey work, the public faces of the congress were the mercurial and unpredictable Scotsman R. D. Laing and his South African compañero David Cooper. Nowadays, Laing’s reputation is in the doldrums. Following revelations about his family life (coupled with his heavy drinking and drug use), his genuine contributions to the non-coercive practice of psychiatry have been devalued. The arch-demystifier has himself become mystified. But in 1967, few anti-Establishment voices carried greater conviction. If you wanted some high-level existential commentary, or if you wanted it “real”, Laing – “Ronnie” – was your man. Indeed, to use the words that William Hazlitt once applied to another radical, the anarchist William Godwin: “No one was more talked of, more looked up to, more sought after…wherever liberty, truth, justice was the theme.”

Cooper’s reputation has followed a similarly downward path. Idolised once as a pioneer of the anti-hospital – in effect, a sort of liberty hall for young schizophrenics – he quickly degenerated, during the 1970s, into a wild man of the medical and the academic lecture circuit. Nonetheless, beyond the congress, he is also notable for introducing English readers – also in 1967, with much help from Laing – to Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilisation, a text that is still in use in many UK universities today. (Not that the Frenchman was ever grateful for the boost to his international reputation occasioned by Cooper’s abridged translation – he later complained that Cooper’s introduction misinterpreted his position.)

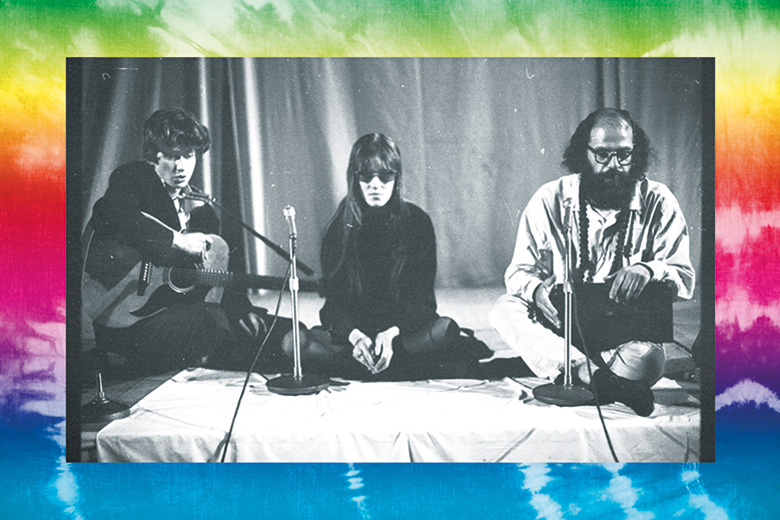

Another striking aspect of the dialectics congress was that, unlike most academic conferences of this or any other period, it brought together not just a host of scholars, but also activists and scholar-activists, many of whom were major public and/or intellectual figures, with magnetism by the bucketful and egos to match. How many people in 1967 were more famous on the world stage than beat poet Allen Ginsberg? Or carried as much ideological heft as Frankfurt School Marxist Herbert Marcuse? Or possessed as much wisdom as anthropologist and systems theorist Gregory Bateson – who alarmed attendees with his talk of global warming?

Then there was the matter of the congress’ venue. The former railway shed in North London was dilapidated then, but it provided the perfect environment for hastily arranged film screenings, impromptu poetry readings, “happenings” and other spontaneous artworks. That lack of organisation – further promoted by a vociferous segment of participants who objected to initial attempts at rough timetabling – further enhanced the congress’ contemporary celebrity.

The intellectual legacy of the dialectics congress has been considerable. Notwithstanding the names mentioned above, the biggest impact was made by a new figure on the English scene: the American Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael.

The Black Panther Party’s future “honorary prime minister” arrived fiery and revved up. He had been repeatedly wound up by Laing at a house party, and was convinced that he was about to be assassinated by one of his enemies. But despite the Johnson administration’s belief that he was at least partly responsible for the race riots sweeping the US’ black ghettos, Carmichael was largely unknown in the UK beyond very small circles of expat American and West Indian radicals. To an overwhelmingly white audience, used to the mostly softer ways of the university debating chamber, his vituperative outbursts must have come as quite a shock.

On his first appearance, Carmichael (who later adopted the name Kwame Ture) introduced the core ideas that he wanted to convey: Black Power and the distinction between what he called “individual racism and institutionalised racism”. The latter phrase, of course, has been common currency in the UK since 1999’s publication of the landmark Macpherson report on the bungled police investigation into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence six years earlier. But, in 1967, the concept was new and, in the context of a society just beginning the long process of coming to terms with other inequalities, was undoubtedly somewhat startling. Carmichael supported his distinction by contrasting the infamous 1963 bombing of a Birmingham, Alabama church by white supremacists, which killed four girls, with the observation that 500 black babies died in the same city each year as a direct result of poverty and discrimination.

Another of his main subjects was the iniquity of the politician, businessman and imperialist Cecil Rhodes. “You see, because you’ve been able to lie about terms, you’ve been able to call people like Cecil Rhodes a philanthropist, when in fact he was a murderer, a rapist, a plunderer and thief…You can keep your Rhodes Scholars: We don’t want the money that came from the sweat of our people.” Although, of course, it would be more than a stretch to connect his speech directly to the modern Rhodes Must Fall protests at Oxford’s Oriel College, Rhodes’ alma mater, the echoes of his arguments are plain to hear.

The congress also saw various higher education shibboleths challenged by the Danish educationalist and philosopher Aage Rosendal Nielsen and two Americans, the social critic Paul Goodman and the Marxist educationalist Allen Krebs. Among their targets were the need for a separate caste of powerful administrators, the regimentation of staff-student relationships and the central importance of examinations and grading.

In all these respects, Cooper, Berke and, to some extent, the other existential psychiatrists were already pioneers. Cooper had argued in the run-up to the congress that the organising group was concerned to rid itself of the “typical alienated and serialised relation of teacher to taught – the relation that is expressed in the typical academic situations of the mass lecture and the formalised tutorial group or dyad”. Meanwhile, Berke had helped to set up the Free University of New York (FUNY) in 1965, which became the model for the London Anti-University that grew directly out of the congress.

Not that the organising group was successful in all its ambitions. Some participants criticised the organisers for keeping what Peace News feature writer Roger Bernard called a somewhat “tyrannical” hold over the microphones and for “blocking genuine dialogue”. Meanwhile, Goodman claimed to have learned nothing new and labelled the conference among the worst he had ever attended. Conceivably, though, he was just piqued, having put up with two weeks of ceaseless attacks from Marxists and other left-wing ideologues.

Most of the participants, nevertheless, seem to have judged the congress a success. Cooper ended it with a ringing peroration, riffing off a story that Marcuse had told about how the Paris Communards had shot at all the clocks so as to “put an end to the time of their rulers…As I look round me now, I see a vista beyond your sea of faces, going way out there. I see a vista of broken clocks. And now, I think, it is our time!”

The congress’ influence certainly lingered long. The London Anti-University, in turn, begat numerous other free universities, including the Free University of Essex, the Free University of Birmingham and, perhaps most interestingly, the London School of Non-Violence. Located in the crypt of Trafalgar Square’s St Martin-in-the-Fields church, the last of those was founded in 1969 by the charity Christian Aid, with the help of Indian activist Satish Kumar. It offered lectures on subjects including William Blake, G. K. Chesterton, Gandhi and non-violent economics, before finally folding around 1975.

Most of the other longer-lasting free universities foundered at about the same time, and experiments in radical higher education were subsequently few and far between until recent years. But whether they know it or not, modern start-ups such as London’s Antiuniversity Now, Edinburgh and Manchester’s Ragged University, Lincoln’s Social Science Centre and even elements of the former Occupy movement are all scions of FUNY, the congress and the London Anti-University. So, too, are the numberless thriving alternative art colleges, which feed off similar ideas.

Most of these organisations, as you’d expect, do not charge high fees; some don’t charge fees at all. Neither do they employ large numbers of administrators, or treat their students as bums on seats – or, even more demoralisingly, as “customers”. Most are organised directly by their students and teachers, those roles often being interchangeable. Many do not even have premises. But all, in their varying ways, are devoted to higher education.

What Laing and Cooper would think about these ventures is difficult to tell: both died in the 1980s. But I suspect that they would not think much of them. As ruthless and persistent iconoclasts, they would probably have found them a little too conformist for their tastes.

But isn’t going against the flow, being critical and even a little troublesome the whole point of higher education? Fifty years may have passed, but recapturing even a little of that spirit would at the very least make this summer’s academic conference season a lot more interesting – and, potentially, a lot more culturally significant.

Martin Levy is special collections assistant at the University of Bradford.

On your own road: Kerouac and countering the across-the-counter culture

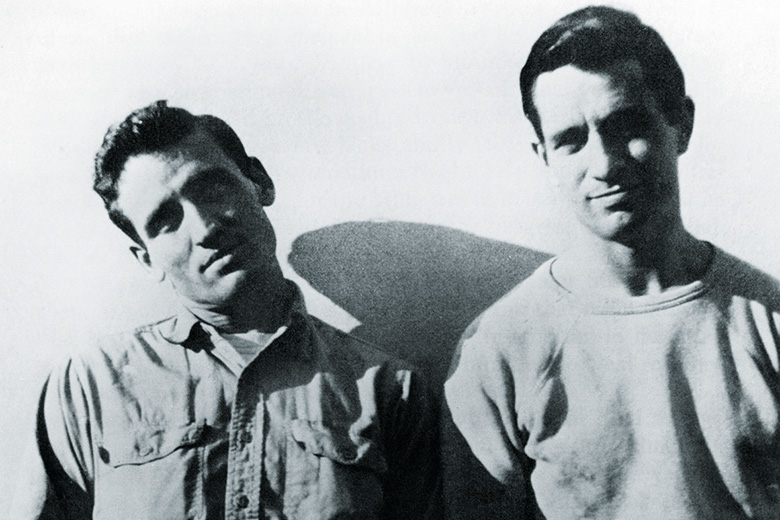

Sixty years ago this September, Jack Kerouac’s iconic novel On the Road was published. The spirit of Kerouac’s crazy travels back and forth across the US in search of “it” influenced a newly mobile generation of students.

The book, legend has it, was typed frantically on a single 120-foot (36m) manuscript (single sheets cut to size and taped together) over a three-week coffee- and Benzedrine-fuelled writing binge in 1951. Six years later, after edits and the changing of names to mask identities (partly because of the publisher’s fear of being sued), On the Road was published, with beat poet Allen Ginsberg renamed Carlo Marx, Kerouac calling himself Sal Paradise and Neal Cassady, their crazy muse, rechristened Dean Moriarty.

The book’s jazz-like improvised stream of consciousness style and its search for meaning “on the road”, rather than in the American dream, resonated with the emerging vibe of the counterculture. Kerouac inspired non-conformism, and the beats’ influence was lamented during moral panics about declining values on both sides of the Atlantic.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover said that beatniks and communists were two of the greatest threats to American culture. And one UK newspaper blamed their influence for the 1961 “Beaulieu Jazz Riots”: a set-to about preferred styles of jazz, with beer and punches thrown. The “Hobo prophet” Kerouac was described by the journalist as a “talented writer” who “prefers to devote his talents to exalting the bums and jazz maniacs of the New York jazz cellars”.

The paper also pointed to British beatniks travelling abroad, especially to France, where “the atmosphere is somewhat more lax, and they can let themselves go”. The beat mode of travelling, in which an outer journey was a catalyst for inner enlightenment, certainly influenced the hippies. The Hippy Trail across Asia, undertaken mainly by relatively well-heeled students and musicians in search of spiritual inspiration, was an expression of the countercultural mood. In 1973, two such travellers, Tony and Maureen Wheeler, typed out and stapled together copies of a travel guide called Across Asia on the Cheap , which contained advice on quality marijuana and bribing Afghan border guards.

Nearly 35 years later, the Wheelers controversially sold a 75 per cent stake in their Lonely Planet empire to BBC Worldwide for nearly £90 million. By then – 2007 – we had entered the era of mass mobility brought about by greater wealth, better infrastructure and cheap flights. But an opening-up of geographical freedom seems to have been accompanied by a closure of a certain existential freedom associated with On the Road.

Youth travel is heavily marketed today in terms of ethical gap years, adventure travel and “voluntourism”. Travellers are given well-intentioned but ultimately conservative counsel to “check their privilege”, “tread lightly” and avoid “cultural appropriation”, while being assured of predefined outcomes from their trips, such as global citizenship and an enhanced CV.

By contrast, the beats and the hippies dropped out of the mainstream in favour of an open ticket to nowhere in particular. For Kerouac, the world was an expanding, experimental realm of freedom to be met head-on, unencumbered by the heavy moral baggage of others.

In Dharma Bums , the 1968 follow-up to On the Road, Kerouac writes: “I saw that my life was a vast glowing empty page and I could do anything I wanted.” If students still felt like that, the modern world might well be on a more interesting journey.

Jim Butcher is a reader in the School of Human and Life Sciences at Canterbury Christ Church University. He has written three books on the sociology and politics of modern travel and tourism.