While arguments have raged about the hike in tuition fees, with thousands taking to the streets to protest, another key element of the coalition government's higher education reforms will be easier for students to swallow: the promise to "radically improve" information on university courses.

By this autumn, every university in England will have published a new set of information about every undergraduate course on offer. These Key Information Sets will include data on areas such as contact hours, graduate salaries and student satisfaction.

But with little fanfare, one institution has already put itself ahead of the game by displaying information about its graduates in a way that could set a benchmark for the sector.

The University of Oxford has created an online tool for comparing data about its graduates' careers and salaries. Tucked away on its main careers website and organised into a set of user-friendly tables, it allows immediate comparisons of the salary and employment status of its alumni from 2008-09 and 2009-10 - undergraduate and postgraduate - sorted by subject area, individual course and even constituent college.

A single click of a mouse produces striking information, including a league table of salaries by college, graphics showing the impact that subject choice might have on employment prospects, and even data that indicate how quickly graduates of particular courses might start to pay off their student loans.

The data are drawn from the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education survey, the national poll of graduates collated annually by the Higher Education Statistics Agency, which asks graduates about their occupation six months after university.

Exposing its DLHE data in such detail sets Oxford apart from most of the rest of the academy, but for Jonathan Black, director of the institution's careers service, it is the natural path to take.

The exposure has exploded a few myths about Oxbridge graduates, too, he adds.

"Without being prescriptive, directed or forming a contract, it is saying we are really open about where our students go," says Black. "We have nothing to hide - and in fact we would quite like to engage people and say: 'Well, why aren't (some of these graduates) getting employed?'"

Black argues that the move allows Oxford to give its students well-directed careers advice while helping prospective applicants with little experience of higher education to make informed choices about what to study.

"You meet lots of old members of Oxford as well as current and prospective students who say: 'Oh, but everyone goes into the City', or 'Everyone becomes a high court judge.' And you say, well, that's not really true, actually."

Black points out that the single biggest employment destination for Oxford graduates is education - "which makes people sit up a bit".

Although the development of the online tool aligns Oxford with the coalition's desire to improve the quantity and quality of student information, Black notes that this was not part of the institution's motivation.

"I think we have been ahead of what the government has wanted but in line with it," he says of the website resource, which the university began work on two years ago.

"We agree that there should be more transparency, but I'm not sure about some elements of the KIS - partly because people need to read it with a health warning."

He believes that Oxford's model gives students a more accurate picture than the data provided by the KIS. The difference is that the ancient university's approach facilitates detailed, easily viewed comparisons between courses, subjects and colleges, whereas the KIS is a fixed template that will display an isolated set of data on a particular course.

Steve Edwards, founder of BestCourse4me.com, an independent website that already uses DLHE data to help students choose what to study, finds Oxford's approach refreshing. He says that many universities have been resistant to the idea of presenting detailed data on the employment patterns of their graduates.

However, he believes that the KIS is still important, as it will provide students with an official, standard source of information that cannot be manipulated by universities keen to market the data in their own way.

"I have absolutely no problem with this sort of thing, as long as it is transparent and accurate and not manipulated in any way that is going to mislead the naive observer," Edwards says.

Oxford appears to have taken a transparent approach, he thinks.

"But I think it is very important that there is a consistent set of measures available centrally that allows people to compare universities, rather than it simply becoming a set of individual marketing exercises for particular institutions," Edwards adds.

Mike Milne-Picken, academic registrar at the Royal Northern College of Music, says that Oxford's model is interesting, but he does not believe it is an option for all universities - especially given the resources needed to develop such tools.

"Good luck to Oxford if it can do it, but I don't think it is a model that would suit everyone. Many institutions will not have the time, staff and money available to invest in creating a system that can offer that granularity," he says.

Milne-Picken believes that improving the DLHE itself is a more relevant aim, given the obvious limitations of data collected just six months after graduation. What is needed is "a way of measuring these things accurately over a longer time frame", he says.

Oxford is well aware of the potential pitfalls of the DLHE data, Black says, adding that the university's intention has been to create a tool that is "directionally sound" and should be used in context and alongside other information.

And by aggregating data from more than one year, Oxford is striving to improve their accuracy.

"To a certain extent we're stuck with [DLHE]," Black explains. "I have published articles saying that the use of DLHE - in, say, the KIS - could be misleading because the salary data are unaudited. But if you think of it as directionally sound then it can be useful: 'This is roughly where people who did English went to in the past couple of years.'"

Universities conduct the DLHE themselves and pass the data on to Hesa. Black explains that one helpful element of this system is the fact that it allows Oxford to contact recent graduates who are unemployed to see if they need help.

"Although the survey is only six months out - and I know it would be ideal to have information five years, 10 years, 20 years after graduation - we can still use it to add value for our students."

Keble quids in, but archaeologists caught between rocks and a hard place

Opening up the University of Oxford's information on employment outcomes allows easy comparison of courses, subjects and colleges with interesting - and sometimes quirky - results.

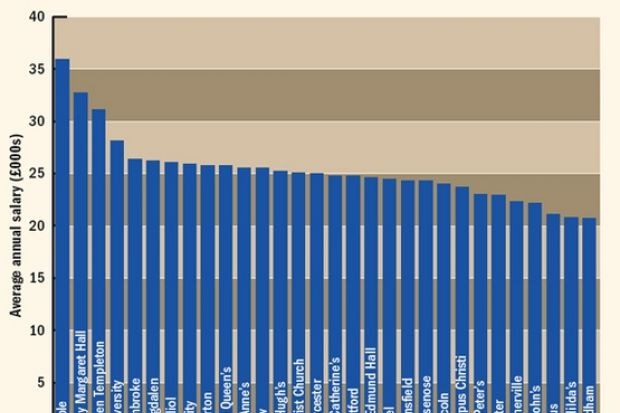

The average salaries earned by graduates of each Oxford college six months after leaving caused a stir when first revealed by student newspaper Cherwell at the end of last year. The data show a spread of more than £15,000 from the highest (Keble College at £35,900) to the lowest (Wadham College at £20,700).

For postgraduates, the difference is even more stark. Those taking postgraduate courses at Christ Church College go on to earn an average of £57,000, while at St Stephen's House - a theological college - the figure is £24,600.

Gender data highlight the pay gap that still separates male and female graduates. For instance, men from Keble earn an average of £45,500 six months after graduating, but for women from the college the figure is £25,900.

Somewhat less surprising is the salary spread for different subject areas: the average for graduates who have taken first degrees in Oxford's medical sciences divisions is £29,200, but for those from the English faculty it is £18,700. Interestingly, history graduates seem to earn more (£23,700) than many others.

The aggregate data from 2008-09 and 2009-10 also suggest that the unemployment rate six months after leaving Oxford is 5.9 per cent. Mansfield College has the worst figure (10.1 per cent). The BA in classical archaeology and ancient history has one of the highest unemployment rates for an Oxford undergraduate course (19.4 per cent).

However, the limitations of the source of the Oxford figures, the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education survey, which polls graduates just six months after they leave university, become clear when former students' occupations are considered. Of the alumni respondents, more than 40 former undergraduates were working as waiters, waitresses or bar staff - a higher figure than the number employed as chartered accountants (25) or mechanical engineers (18).

Meanwhile - and possibly of interest to the Treasury - the tables reveal the percentage of alumni earning under £21,000, the threshold at which graduates will start repaying student loans under the new fees regime. For those who took humanities courses, the proportion is a hefty 51 per cent - far higher than for other subjects, including the social sciences (25 per cent).