When the German director Margarethe von Trotta was approached to make a film about philosopher Hannah Arendt’s coverage of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, she was less than enthusiastic. “How”, she asked, “can I make a film about a philosopher, someone who sits and thinks?” Putting intellectuals on film, she assumed, would not be easy: sitting around and thinking is pretty much what they do. It is true that there is precious little cinematic excitement in the academic’s day-to-day, typically more a case of Bob Jones and the Board of Studies than Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Yet many philosophers have actually led very interesting and rather colourful lives, so the paucity of films about philosophers – fictional or real – has always struck me as surprising. I’ve often felt that a colour-drenched, hauntingly opulent biopic of Frankfurt School aesthete Walter Benjamin – directed by Baz Luhrmann, of course – would offer a pretty thrilling ride: Moulin Rouge meets dialectical materialism.

Recent blockbusters have focused on the stories of mathematicians and physicists rather than their cousins in the philosophy faculty. Last year saw the release of The Imitation Game, about Alan Turing, and The Theory of Everything, on the life of Stephen Hawking. We might also point to the success of Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind (2001) on game theorist John Nash, and Good Will Hunting (1997), in which Matt Damon plays a troubled mathematics prodigy. The protagonists in these films spent their lives grappling with the kinds of questions that non-specialists surely fail to grasp in any depth, but studios have been undeterred. As anyone who has taught undergraduates knows, getting an audience to invest in a subject that they know nothing about isn’t easy. The film-makers manage to get around this by placing the emotional lives and relationships of these characters front and centre, which allows the audience to see their intellectual work as the elaboration of personal and internal conflicts.

This compromise presents plenty of difficulties, however: a New York Times critic described The Theory of Everything as “a drive-by muddling of Dr Hawking’s scientific work, leaving viewers in the dark about exactly why he is so famous”. Splicing intellectual content with dramatic excitement inevitably means diluting the former, with mixed results: in that review, the specific crime was moving away from showing how Hawking “undermined traditional notions of space and time” and instead “pander[ing] to religious sensibilities about what his work does or does not say about the existence of God, which in fact is very little”.

All of this meant that Woody Allen’s latest film – an attempt to get philosophy into a more traditional cinematic mode – caught my eye. Allen has always liked to think of himself as a fairly cerebral film-maker – we might note Marshall McLuhan’s cameo in Annie Hall (1977), or the allusions that Match Point (2005) makes to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. The production notes for Irrational Man boast of the film grappling with “big ideas”, too. So how far would the film go in exploring genuine philosophical questions and arguments? And would this be at the expense of the narrative or our emotional engagement with the characters?

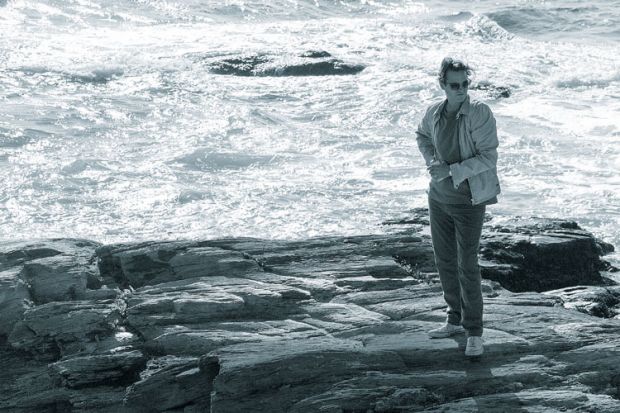

Irrational Man, opening in the UK this week, stars Joaquin Phoenix as the paunch-bearing semi-alcoholic philosopher-depressive Abe Lucas, who can’t finish his book on Martin Heidegger. Abe is to teach for the summer at the fictional Braylin College, the kind of sun-dappled setting that tells the audience that romance must be in the air. Many of the regular tropes of the campus novel are there, especially in their David Lodge (Changing Places) or Philip Roth (The Human Stain) manifestations. Abe finds his intellectual endeavours hopeless: all of his protests and activism are pointless, philosophy is just so much empty verbiage and he is so jaded and nihilistic that he uses phrases such as “the painkiller of an orgasm”. Of course, this makes him irresistible to the student body and faculty, rather than the kind of person who, in reality, you would avoid at a conference.

Inevitably, his most talented student also happens to be the youngest and most attractive woman in his class, Jill Pollard, played by Emma Stone, who writes a paper that apparently offers stern critique of Abe’s own work, and his interest is piqued. (Off screen, if you thought that your undergraduate students were writing work that really did chip away at the foundations of your own, you would probably conclude that you had been drinking too much and/or that you needed to think very carefully indeed about the next cycle of the research excellence framework.)

Jill’s parents are uptight professors. Jamie Blackley plays her sweet boyfriend Roy, a rather bland character who wears cable-knit sweaters, so his fate as a cuckold is more or less sealed from the start. No wonder Jill can’t resist Abe, who takes regular nips from his hip flask, egregiously misrepresents Kant’s categorical imperative, and plays Russian roulette at a frat party to express his intellectual interest in chance and indeterminacy. For the first half of the film, Allen gives us a quirky campus rom-com with the occasional quotation from Kierkegaard dropped in, all backed by the jangling jazz piano of the Ramsey Lewis Trio.

Films about philosophers that tread the line between biopic and narrative cinema are more often ruminative and discursive. Most recently, Martin McQuillan, pro vice-chancellor of research at Kingston University, and director Joanna Callaghan embarked on an ambitious dramatisation of Jacques Derrida’s The Post Card – a gorgeous, if unreadable, 1980 book on letter writing, the signature, love, Socrates, and death, consisting of fictional “love letters” and essays on Freud. Love in the Post (2014) embraces Derrida’s formal and thematic eclecticism: around the central relationship of a fictional literary scholar and his enigmatic wife orbits critical commentary on Derrida from leading academics, and Callaghan’s reflections on filming the unfilmable. The film is disconcerting and enchanting; its elusive quality summons the expansiveness of Derrida’s thought.

But it is not exactly a film that one watches for the plot. It can be pretty difficult to inject into philosophising the sort of concrete cinematic excitement one needs for traditional blockbusters – hence the Russian roulette scene in Irrational Man.

Nevertheless, Allen’s film makes a bold attempt. In its middle third, he splices the campus rom-com with something akin to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope or indeed Strangers on a Train. Abe, overhearing a chance conversation in a diner about a custody battle and a corrupt judge, decides he is perfectly placed to commit the perfect murder, unknown to the judge and seemingly without motive.

This is a truly epiphanic moment for Abe: he starts eating breakfast, is able to get an erection again, and starts enjoying long walks along the beach. Murder becomes an act of metaphysical and personal significance far more meaningful than helping victims of Hurricane Katrina or writing to The New York Times, activist commitments he now disdains. This becomes his obsession, and we tumble deeper into his scheming internal monologue.

Thankfully, the murder plot does restore a bit of energy to the rather tired narrative and marshals a bit of philosophical meat for the film. Abe’s decision to murder the judge might perhaps be read as the inversion of André Breton’s famous dictum: “The purest surrealist act is walking into a crowd with a loaded gun and firing into it randomly.” Abe, in contrast, hopes to commit a very particular murder. However, as the delicious twist in the film’s denouement shows, it is randomness and contingency that unpick his carefully stitched plan. I hope I am not giving the film too much credit to suggest that it ironically deflates Abe’s ludicrous self-aggrandisement of his “one meaningful act” by showing a world of much greater chaos and complexity than his rather solipsistic obsession with individual “choice” and “freedom” can comprehend.

One of the delightful things about Love in the Post is that its ironic, self-reflexive style can puncture some pretences; Abe would be a much more engaging character were his narcissism deflated from time to time as well, but the film offers little such distance. The soft-edged pastels of the movie’s visual style do rather take the bite out of any of the “big ideas” Allen claims to be so keen on in the production notes for the film. There are probably fewer brisk summaries of the great thinkers of the philosophical tradition than there are luminous shots of undergraduate women’s legs passing through scenes (a visual tic clocked immediately by a colleague who accompanied me to the screening). The Atlantic was scathing: Allen’s latest film is “dark tedious fantasies”, filled with his “specific predilections and neuroses”.

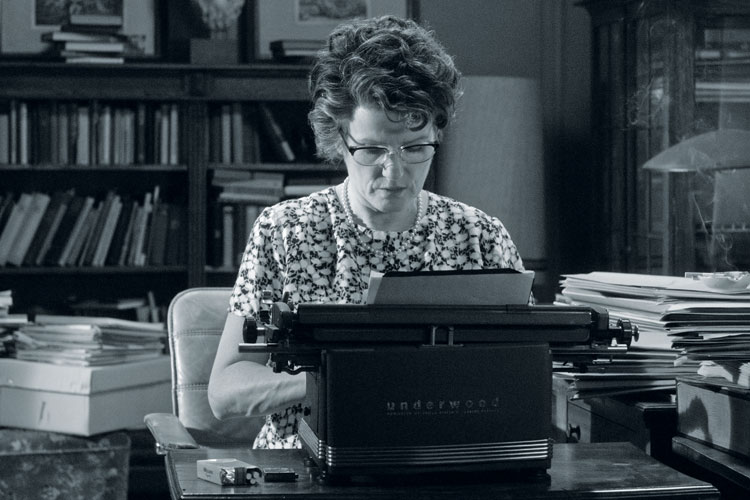

So how does Allen’s effort compare with other attempts to bring philosophy to the silver screen? Despite her initial concerns, von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt (2012) turned out to be a good example of a rather more intellectually substantial narrative movie. Representing people sat around thinking is tricky, but a nicely stylised setting can help. As Arendt (played tautly by Barbara Sukowa) ruminates in Jerusalem on the writing of Eichmann, we are treated to periodic montages of her lying on the couch smoking, or tapping furiously at her typewriter, all in her beautifully detailed Upper West Side apartment.

Arendt’s relationship with her mentor and former lover Martin Heidegger is a key part of the character’s development. The film is partly effective because it intertwines her philosophical interest in questions of thought and being as they pertain to the Eichmann trial with her personal attachment to Heidegger himself (played by Klaus Pohl). Characters in the film claim that her romantic commitment to Heidegger’s German metaphysics has distanced her, as a German-Jewish émigré, from her “true” Jewish identity. It is this relationship that drives Arendt’s antagonism towards the spectacle of the trial of Eichmann in Israel and her questioning of the Jewish Councils’ role in the Holocaust.

But for a masterclass in putting what Adorno called “the melancholy science” on film, one must turn to 2013’s French-language Violette, directed by Martin Provost. Violette follows the wilful and brilliant French novelist of the post-war period Violette Leduc, author of In the Prison of Her Skin and Starved, performed with vulnerability and panache by Emmanuelle Devos. The motor of the film, however, is her relationship with Simone de Beauvoir, played, as The New York Times put it, as a “cross between a dominatrix and a mother superior”, by the austere Sandrine Kiberlain.

De Beauvoir is Leduc’s mentor, and she brings political and intellectual intensity to her work: “Write it all down! Tell it all! You must go further!”, she exhorts Leduc, on reading an early draft of her masterpiece In the Prison of Her Skin. She is a staunch defender of Leduc’s explicit and painful novels about women’s experience to the easily cowed and misogynistic Parisian publishing set.

Their scenes together are breathtaking: de Beauvoir is forbidding, cold, scolding and also nervous of the prospect that Leduc’s talents may eclipse hers. Leduc’s obsession is initially suffocating, and she reproves her emotional outbursts, as if Leduc’s pain waters down de Beauvoir’s stern existentialist philosophical project, even as she comes to need Leduc as much as the latter does her.

The internal, uneven power struggles of their own relationship communicate the crackle and fizz of a political and philosophical coming-to-consciousness for both writers, as de Beauvoir completes The Second Sex and Leduc writes of her experience as a woman who has been thwarted her entire life.

The stakes for philosophy, and the relationships it allows us to have with others, are much higher in Violette than they are for Abe, whose plans to commit murder are just a route to some kind of fuzzy self-actualisation. Using thought to try to transform the world in Violette is fraught, dangerous and emotionally exhausting; in Irrational Man, the best that philosophy can do is resurrect the flagging libido of an ageing college professor. Whatever your expectations of Allen’s latest film, if you were hoping for something that draws a wider audience in to the cut and thrust of intellectual argument and reflection, then this isn’t it: instead philosophy is reduced to fridge magnet soundbites that help Abe to justify his criminal actions. Let’s hope that, in future, more film-makers find the means to dramatise how intellectually electrifying philosophy can be.

Benjamin Poore is a teaching fellow in the School of English and Drama at Queen Mary University of London. He is also Arts and Humanities Research Council researcher-in-residence at the Freud Museum.

后记

Print headline: Entertaining thoughts

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?