When universities in many countries suspended face-to-face teaching earlier this year as the first Covid-19 wave gathered deadly momentum, scholars could have been forgiven for seeing several silver linings to that dark cloud. One, of course, was the fact that teaching from home meant they were no longer required to risk infection on campus. But another was the welcome break that it offered from the daily grind that many academics face of commuting to university towns many miles from their family homes – or even spending weekday nights in Airbnb lodgings or locally living colleagues’ spare rooms.

“Everyone at my university was delighted when we went online,” admits one lecturer at a Russell Group university who, until Covid struck, for years had spent Monday to Friday exiled from home during term time, returning to London only at weekends.

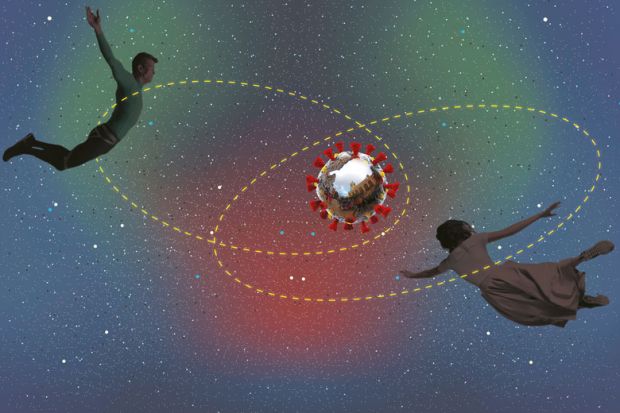

Although all working couples can struggle to find attractive jobs in the same city or even region, the scarcity of academic posts and the fact that cities rarely contain more than two or three universities makes the problem particularly fraught for academic couples. Indeed, the phenomenon is so common that it has even acquired its own darkly humorous name, co-opting that of a well-known puzzle in classical mechanics.

The “two-body problem” is illustrated by the situation of Siobhan Talbott, senior lecturer in early modern history at Keele University. On the days when she needs to be on campus, she drives the 50 miles to the Staffordshire town from her family home in Liverpool, leaving home at 6.30am to arrive at 8am and staying until after 6pm to avoid the worst of the traffic.

“It means I don’t see my children on these days,” she says. Instead, the childcare falls to her husband, also a historian, who is based at the University of Liverpool. “We decided against living in the middle – between Keele and Liverpool – because we have two small children, so one of us needs to be close to nurseries and school,” explains Talbott, adding that the couple are also reluctant to lose the support network they have established in Liverpool.

Her situation can leave friends from outside the sector scratching their heads, admits Talbott. “They will say that it sounds really arduous. But when you tell someone in academia, the reaction is very different: they think we’ve hit the jackpot by both getting permanent jobs within touching distance [of each other]. We feel it is a relatively small price to pay to have the careers we do…but if it was five days a week, I couldn’t do the job.”

Talbott and her husband met when she was beginning a doctorate and he was completing his; by the time she obtained her doctorate, he had secured a permanent position at Liverpool. The “trailing spouse” in heterosexual couples is not always the woman, of course. Dame Athene Donald, master of Churchill College, Cambridge, points out that her own appointment in 1985 as the famous Cavendish Laboratory’s first female physics lecturer prompted her husband to give up his own research ambitions and become the primary carer for their children. However, she does believe that the two-body problem disproportionately affects women because they are more likely to have an academic spouse.

The evidence for that claim is not plentiful but is attested to by a 2009 poll of 30,000 academics at 13 leading US universities, carried out by Stanford University’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research. It found that, overall, 35 per cent of male academics and 40 per cent of female academics were married to other scholars, but, in many disciplines, the proportions were much higher; 80 per cent of female mathematicians were married to other mathematicians, for instance.

“There is something unusual about academia – you don’t tend to see medical doctors marrying other doctors at the same rate,” remarks Donald. With female academics often a few years behind their academic partners in career terms because of their lower average age, they often have particular problems juggling family life with the need to “show you are not a one-trick pony” by moving between universities before being offered a permanent job.

“There is a certain 1950s view that informs academic careers – it is based on the idea that the professor with the stay-at-home wife moves around the world, continually increasing their status and prestige,” she says.

That picture is even further from the reality of same-sex partnerships. Elena Rodriguez-Falcon left the University of Sheffield in 2018 for the new Hereford-based university known as the New Model Institute for Technology and Engineering (NMITE), where she is now president and chief executive officer.

“My partner Tracy’s life centred on her children and her job as a teaching assistant, but she said this was too exciting an opportunity for me to turn down,” Rodriguez-Falcon recalls. “But it still feels an imbalance when [one partner’s] opportunities and aspirations are entirely driving the domestic situation…While Hereford is a lovely place to live, it maybe does not have the same opportunities [for partners] as Sheffield; that’s part of the reason that I wanted to join NMITE: I wanted to change that.” In the meantime, however, Rodriguez-Falcon’s partner is having to retrain as a counsellor in a local college.

Moreover, the two-body problem is more than just a work-life balance issue, Donald points out. It also accounts for much of the gender pay gap in academia, particularly at professorial level, she believes. “Men will apply for positions that they might not really be serious about because they feel they could move if they wanted – even if they don’t take the job. [The threat of moving on] gives them some leverage for a pay rise at their current institution,” she explains. However, their husbands’ more senior positions mean that women often “cannot get into that bargaining position, partly because the challenge of relocating [for the couple] is so much greater”.

Indeed, even those women who, despite everything, have reached the very top in science and academia often speak of the difficulties of combining family life with academia. Accepting the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last month, for instance, Emmanuel Charpentier mentioned the “price for my personal life” she had paid when moving from Vienna to Sweden’s Umeå University in 2008, where she played her part in discovering the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing technique. That move was one of many: she told an interviewer last year that she has worked in five countries and seven cities during her 27-year scientific career.

Other successful women have spoken of their relative fortune regarding their partners’ situations. For instance, Dame Ottoline Leyser, who recently succeeded Sir Mark Walport as chief executive of UK Research & Innovation, described in her 2015 Royal Society report, “Parent Carer Scientist”, how her late husband’s flexibility as a freelance writer had allowed her to take research posts in the US.

Those towards the top of the university ladder seem just as exposed to the two-body problem as those starting out in academia – even if the financial impact of long-distance commutes or renting a second property is less keenly felt. Moreover, those in senior university management often have little choice but to leave their families during the week, many say privately.

“I have seen quite a few marriages involving academics or senior university staff fail in these circumstances,” observes Ferdinand von Prondzynski, who was principal and vice-chancellor of Aberdeen’s Robert Gordon University from 2011 to 2018 – during which time his wife remained a professor at Trinity College Dublin, 400 miles away. “It’s a very common arrangement among vice-chancellors – in fact, I struggle to think of any university leader in my time who did live in the same place as their partner,” he adds.

In his case, von Prondzynski would typically leave Aberdeen on Friday evening and fly back on Monday morning. “It would mean catching the 4am airport bus to reach your office on time – luckily, I wasn’t someone who needed a lot of sleep, but I can see that not everyone could keep doing that for several years,” he says. Nevertheless, a university leader would not expect any sympathy for such a punishing schedule. “Vice-chancellors cannot really talk about these things – or anything personal at all – credibly,” he reflects. “The response is always: ‘Look what you get paid; you can put up with it.’”

Prior to moving to Robert Gordon, von Prondzynski was Dublin City University’s president for a decade, so he also has extensive experience of the two-body problem from an employer’s perspective. Not that it was something that often came up at interview; recruitment panels are wary of probing too deeply into candidates’ personal circumstances “because you could face charges of discrimination as people would wonder about your motivations for asking about it”, von Prondzynski says. “We would ask if the person intended to move here because you cannot do the job remotely, but you generally only find out about these things later, when appointments are made.”

Candidates themselves, of course, are wary of mentioning their unwillingness to live close to the university in question for fear of appearing uncommitted. However, leading spouses – especially at more senior levels – sometimes ask universities to find their partners a job in the university or – for non-academic partners – the city in question as a condition of their taking the offered position.

Arranging a “courtesy appointment” for the trailing academic spouse is “much easier” than finding an external position, according to Stephen Trachtenberg, president emeritus of George Washington University. “You have to encourage a culture of cooperation between departments so that [a trailing spouse] might be appointed jointly to, say, the history and law departments if this fits that [their] expertise,” he says.

But expertise is crucial, he adds – and it isn’t always in evidence. At George Washington, which he led from 1988 to 2007, “we wanted to hire a highly qualified woman candidate, but she would not come unless we gave her husband a tenured job. Frankly, he was not very competitive, so we had to let them go,” he recalls.

For many institutions, financial constraints also loom large in considerations about dual appointments, says Warren Bebbington, who was vice-chancellor of the University of Adelaide from 2012 to 2017, and was previously deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Melbourne.

He acknowledges that “even within Australia, where fly-in, fly-out employment in some regional and remote centres is not unusual, the survival of a relationship where the spouses are separated by huge distances can be very challenging, unless the arrangement is only short-term”. Hence, his view “has always been that an enticement for a professional spouse should also be offered as part of the negotiation”. Unlike Trachtenberg’s US experience, however, Bebbington has found that while a position can be relatively easily arranged for a partner in other professions, such as school teaching, where jobs are relatively plentiful, “when the spouse is also an academic looking for a tenured role, that is a much more difficult feat to bring off. Academic schools with tight budgets and rare, hotly contested vacancies can seldom manufacture an opportunity on demand simply to facilitate recruitment to another department.”

And while Bebbington has been keen to lure talented overseas scholars to Australia – with increasing success since the 2016 Brexit vote and US election – he, like Trachtenberg, has baulked at some requested family accommodations.

“I had one couple wanting the university to transport their rather elderly family car across the globe to Australia, but the transport cost would have exceeded the car’s value,” he explains. He also presided over several cases in which “at the last minute, a request would suddenly be made to commence duty one or two years after the advertised start date,” which he attributed to “family tensions or a reluctance to commit to a move at all. In such cases, my custom was to stand by an offer that matched the university’s normal practices: to do otherwise would have invited other complications.”

With joint appointments difficult and expensive to arrange – and virtually unheard of at junior levels – many observers believe that the two-body problem needs more radical remedies.

For his part, von Prondzynski thinks that the time has come for universities to grapple with the issue more seriously given the rise of dual-career couples: “When I started as an academic in 1980, the overwhelming majority of male academics were either single or had wives whose jobs were deemed less significant than their husbands’ – or they had no job at all,” he recalls. “All of the women in any kind of senior position were single, without exception. This is no longer the case and it is something universities need to reflect on.”

Indeed, even before the pandemic and the normalisation of remote working in the academy, there were signs that at least some universities were becoming less insistent on regular physical presence on campus. For instance, Luke John Murphy, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Iceland, has been given permission to base himself 1,000 miles away in Denmark, where his non-academic wife works. This arrangement follows a series of postdoctoral research posts in England, Sweden and Iceland during which Murphy lived away from his wife, who remained in Denmark after the couple moved there for Murphy to start his PhD in 2013.

“We had hoped to see each other every three weeks, but we started to do longer trips every five to six weeks instead as it was a whole day’s travel either way and cost quite a lot of money,” he says. The long separations led to “some rocky patches” in their relationship; “It was sometimes small things: I had my own household so I’d put the milk in a different place to her, or my wife would want to go out and see friends but I’d be too tired from all the travel,” he says. But given the limited number of academic posts related to his specialism – pre-Christian religions – Murphy felt obliged to take suitable posts whenever they arose. “My partner has been extremely supportive for more than 10 years – she wants me to have an academic career but shouldn’t have to give up her own career,” he adds.

Since he is on a research contract, his university has agreed that he can work from home. However, “Iceland is a very informal country and they understand that I have a wife and a life in Denmark. If it was a different culture, they might not be so accepting,” he reflects. Moreover, he doubts that his arrangement would work for all academics – or even for all those on research-only contracts. “Not everyone can take books home with them – and I cannot be as involved as I want to be in university life. At the moment, I have decided my home life is more important than my academic life in Iceland.”

Other scholars have taken advantage of the Covid crisis to work remotely, too. One early career researcher told Times Higher Education that he and his partner had moved to southern Europe and sublet their flat in London during the pandemic while he continued to travel, when required, to his Russell Group university in the north of England. Although he “faced some backlash when I told my university that I would work from London and travel up”, he has had no pushback regarding his move even further away. “It’s definitely a new benefit,” he says. “For research fellow jobs, it opens things up a bit more as I can quite easily do the job from far away.”

For Murphy, the creation of “semi-formal networks of researchers on Facebook” since March could help home-based researchers stay connected to others within their disciplines. “During lockdown, I had a lot more contact with fellow researchers – those people who I previously met once or twice a year, I now met [online] once a month – and even senior scholars are doing similar things,” he observes.

For Keele’s Talbott, continuing to hold some departmental events online would also ease her need to commute, noting that “there are times when I’ve come to Keele solely for an hour’s meeting, which means three hours’ travel”. That said, she would be reluctant to “shift too far from a campus-based university”.

George Washington’s Trachtenberg agrees that allowing digital interaction to continue to predominate beyond the end of the pandemic would have its hazards. “As a university president, you are trying to build a community of scholars – you need scholars to bind together and be available to colleagues and students,” he says. “If someone is constantly thinking ‘I need to hit the road and beat the traffic’, they don’t tend to participate much in campus life or governance and it’s harder to establish that idea of an institution.”

Trachtenberg admits that he has not always been sympathetic about the two-body problem, particularly when he was a dean at Boston University in the 1970s. “I used to think that we were surrounded by universities in Boston, so if the partner cannot get a job at a nearby university, they can’t be a very good academic,” he recalls. “I’ve also worked with vice-presidents whose spouses refused to move with them, so they would return home at weekends – I was sceptical about those arrangements as, somewhere along the line, someone will end up having an affair,” he adds.

That attitude softened when he was appointed president of the University of Hartford, Connecticut, in 1977. “We found a significant number of our music faculty lived in New York and commuted up a couple of days a week because it was very important for them to be wired into that city’s cultural scene,” he says. “There was never enough of a music community to bring these people to Hartford, whereas historians did not have that same issue.” Hence, consideration about limiting on-campus commitments should vary by department and location, Trachtenberg says.

Caution is also expressed by von Prondzynski. In particular, he advises university leaders who are tempted to continue working from their family homes beyond the pandemic to think again. “You cannot run a university if you are not physically present – it is important that you are there and visible,” he says. And Trachtenberg believes that the long-term changes to academic culture wrought by the pandemic will be fairly minimal.

“We may not go back to exactly how things were, but we cannot continue this current socially distanced model in perpetuity,” he says. “It is relying a lot on the momentum built up from pre-Covid days – we have the memory of what was said in meetings and committees, but this will start to erode. We will eventually need to restore the idea of scholars meeting together.”

Nevertheless, academic couples may yet hope that universities – particularly those outside large cities with multiple institutions – will be encouraged by the digital experiences of the past few months to be less insistent on constant presenteeism regardless of personal circumstances.

While the coronavirus may have wreaked havoc on academia, hope remains that it may yet provide a remedy for the worst ravages of the two-body problem.