Since Times Higher Education’s latest annual analysis of the pay packages of UK vice-chancellors was published, the focus on leaders’ remuneration has ratcheted up a fair notch or two.

That June survey (produced in association with Grant Thornton) ushered in a summer of relentless attacks on universities’ pay awards from the media and politicians. Such was the bashing that it prompted Louise Richardson, head of the University of Oxford, to tell the THE World Academic Summit last week that it was “mendacious” to suggest that pay awards were linked to the hike in tuition fees in 2012 to £9,000.

So is it misleading to say that vice-chancellors’ pay packages have benefited from the rise in fees?

One way to test this question is to go back and examine leaders’ pay in 2010-11, the year of the Browne review of higher education funding in England and the decision to put up tuition fees, and to compare that with remuneration for the latest year for which figures are available, 2015-16.

Looking at universities where there were no changes in the vice-chancellor in either of the reference years (for this can skew the figures) shows that on average leaders received a total pay package (including benefits and pension contributions) of almost £242,000 in 2010-11 and of just over £278,000 in 2015-16, a rise of 15 per cent. Factoring in inflation puts the average for 2010-11 at £260,000 in 2015-16 prices, meaning they saw remuneration rise by 7 per cent in real terms over the period.

This might not seem a huge increase, but comparing it with the pay trends for rank-and-file academics suggests that vice-chancellors have fared much better in the age of austerity. For instance, average pay for all academic staff dropped in real terms by 2.8 per cent from 2010-11 to 2015-16 and by 3.1 per cent for professors (although these average salary figures do not include pension contributions).

What would potentially raise the most eyebrows in terms of vice-chancellors’ pay is the huge variation between institutions in terms of increases over the five years: out of 114 universities where the data were comparable, there are 44 where the cost of the leader’s office went up by 20 per cent or more (almost 12 per cent in real terms).

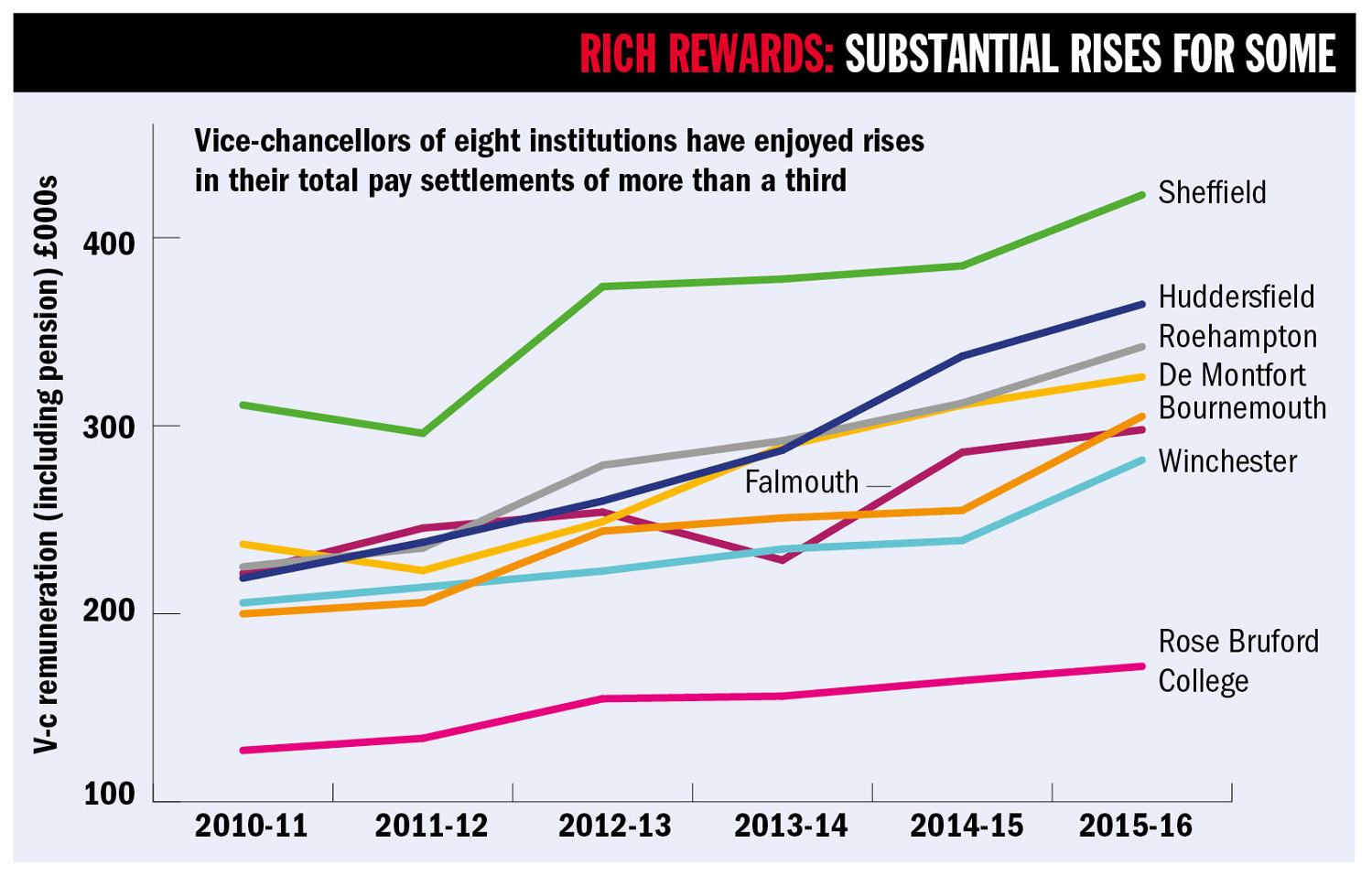

An even clearer comparison of pay packages can be gained by looking at only those universities that had the same vice-chancellor in 2010-11 as in 2015-16. Among these 57 institutions, eight vice-chancellors saw their total pay settlements rise by more than a third in cash terms.

The list is headed by three universities where overall remuneration increased by more than half in cash terms: the University of Huddersfield, where Bob Cryan has seen his overall remuneration rise by 67 per cent over the period; Bournemouth University, whose vice-chancellor John Vinney’s pay and pension award grew by 53 per cent; and the University of Roehampton, where Paul O’Prey’s overall pay package expanded by 52 per cent.

However, the responses given by the universities demonstrate how difficult it is to find common explanations for such uplifts, other than that the institutions believe that the 2015-16 pay packages are not out of line with the rest of the sector.

Huddersfield said that Professor Cryan’s salary had been frozen at his own request before 2010-11 because of the conditions in the economy and was in the lower quartile for pay in the sector at the beginning of the period. “Sustained high-level performance” since then had seen it rise to a level that was “still 20 per cent below that of the highest paid vice-chancellor”.

A Bournemouth spokesman said that its vice-chancellor’s increases had brought his pay “in line with the sector average”. The reward structure, he continued, was “reflective of the positive development of the university over this period”.

And a spokeswoman for Roehampton said that Professor O’Prey was “one of the longest-serving and most experienced v-cs in the country” and his pay was “just over the national average for this role”. She also pointed out that the 52 per cent figure was affected “by actuarial adjustments to a pension scheme”.

In terms of when fees rose in 2012, the graph for the top eight risers for vice-chancellor remuneration suggests that there was no sudden uplift, as by and large the increases were relatively evenly spread over the period. However, fees replaced direct grants for teaching slowly over a number of years as each cohort of students paying £9,000 fees started courses, so it is difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when fees changed university finances.

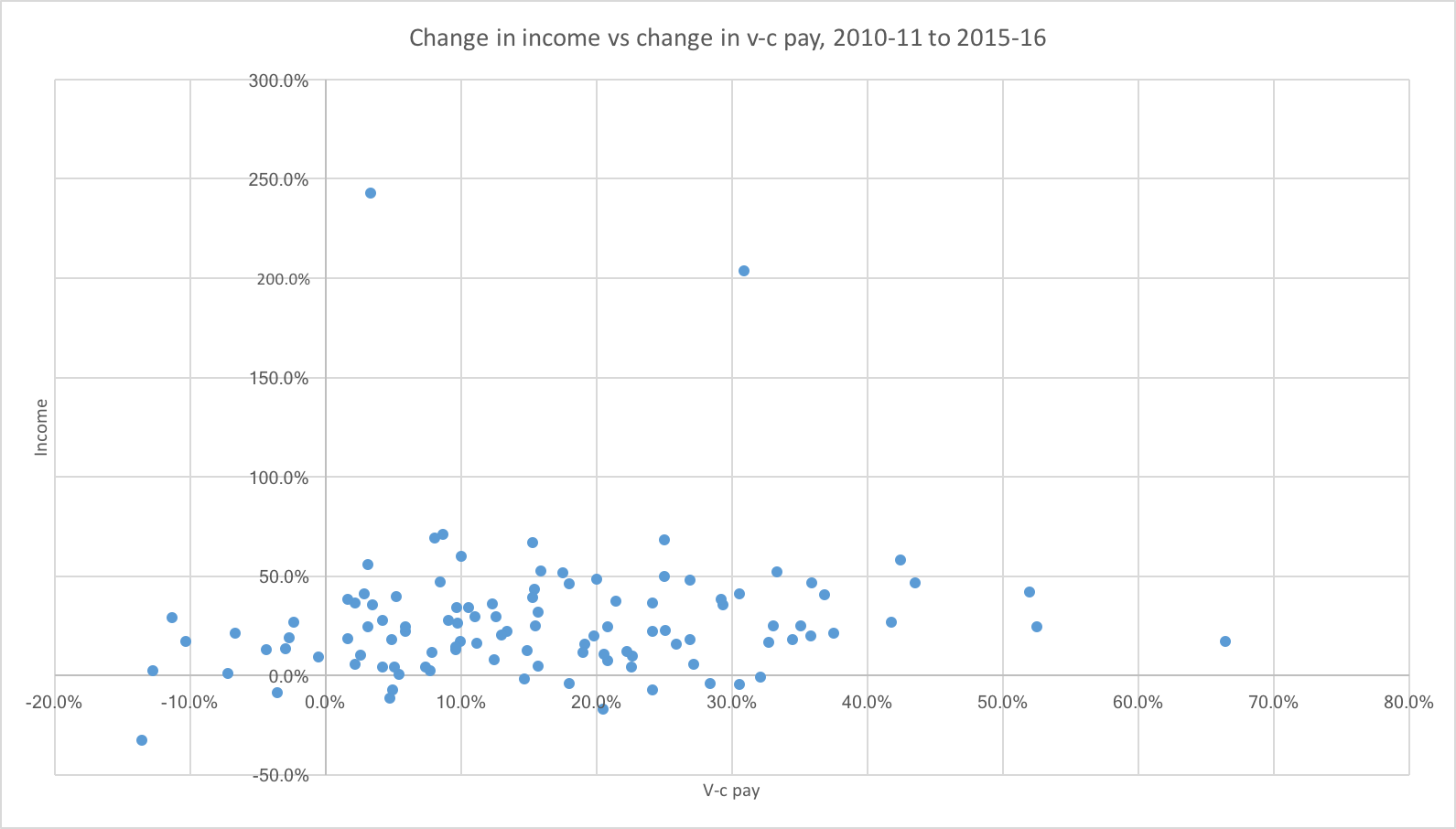

Another way to examine this question is to consider increases in university income – in essence revenue – over the period, since those institutions that may have benefited most from higher fees by increasing their intake would have seen a boost in their overall income (although there are many other factors that could have affected income, of course, including research performance).

Comparing vice-chancellors’ pay increases and changes to institutional income over the time frame also appears to suggest no correlation, with universities that saw roughly the same percentage change in income having wildly different uplifts in pay.

So assuming that this demonstrates no link between the fees rise and pay, what else could be behind the undoubtedly large increases for some leaders in the sector?

One factor that is often cited by vice-chancellors and others is the global marketplace that now exists for university leaders.

The latest figures available suggest that the average university president’s pay at a public institution in the US is $521,000 (£398,000) and A$890,000 (£546,000) in Australia – both much higher than the figure for the UK.

According to data published by the Chronicle of Higher Education, which collates presidential salary information in the US, and The Australian, which does the same for university leaders in Australia, these averages have gone up by more than 20 per cent since 2010-11, again higher than the UK.

John Rushforth, executive secretary of the Committee of University Chairs, the UK association for university governing bodies, said that the nature of the global market “can certainly influence the level of pay at recruitment stage, and then again it can also influence the pay of existing vice-chancellors, since institutions will want to retain a successful [head]”.

He added that although not all universities recruit internationally, there could also be a “trickle-down effect” of higher pay packages to other institutions, especially as there is transparency on pay with remuneration levels published in financial accounts.

“[The] CUC encourages transparency, but it does mean that people who are paid less know they are paid less,” he said.

Mr Rushforth said that the CUC was set to discuss the issue of vice-chancellor remuneration and fairness next month with questions such as “how do we define fair remuneration and how do we encourage transparency in terms of leaders’ pay” up for debate.

He was clear that he had so far seen no “evidence to support [the] contention” that increasing pay was linked to rises in tuition fees.

But the arguments are sure to rumble on, especially as there is no doubt on the basis of the figures that the vast majority of vice-chancellors’ pay packages are only going one way.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view