UK universities’ borrowing costs are spiralling, with banks seeking more control over the money they lend and high levels of pre-existing debt threatening to topple some institutions.

After years of expansion driven by low-cost loans, difficulties obtaining capital have halted all but the most urgent estates development projects across the sector.

Several universities that borrowed heavily during a buoyant period after the tuition fee rise in 2012 face the added complication of some of these loans – issued on five- or 10-year deals – maturing in the coming years, forcing them into expensive refinancing agreements.

With universities faring considerably worse financially than they were a decade ago – and interest rates up across the board – institutions will inevitably also face stricter terms and conditions on new loans, with those already in the worst financial state the hardest hit.

One chief financial officer said the rest of the decade would see a “wall of debt maturing” that looked very difficult to refinance, a situation that increased the need to put the sector on a more viable financial footing so lenders will step up.

A key issue is cash flow, which banks must determine to be stable before sanctioning a loan to an institution. A report from the Office for Students last month found that 40 per cent of English universities may have less than 30 days’ liquidity by the next academic year.

Difficulties borrowing from traditional lenders have led many finance departments to look elsewhere, said James Brackley, a lecturer in accounting at the University of Sheffield who has been tracking university finances as part of a grant-funded project. He said he had seen a shift towards international lenders, which have the potential to be more “aggressive”.

“Institutions could find themselves in trouble if they have borrowed too much, too quickly with a lender that is then being more hawkish,” he warned.

Bob Rabone, a former chair of the British Universities Finance Directors Group, said a lot of the borrowing in the sector was on longer-term deals, covering 20, 30 and even 40 years.

But this debt tended to be held by what he called “early adopters”, the larger, more stable institutions that remain attractive to lenders.

Much more vulnerable were those with bank arrangements of shorter durations, added Mr Rabone, who was the University of Sheffield’s finance director and now works as a consultant for Halpin.

If refinancing was combined with big existing commitments to capital projects but falling student numbers, some institutions could face a “perfect storm”, he warned.

Others that are not in this “dire category” might still have “difficult conversations with banks”, Mr Rabone said, if their position is no longer as sound as it was when they arranged the loan.

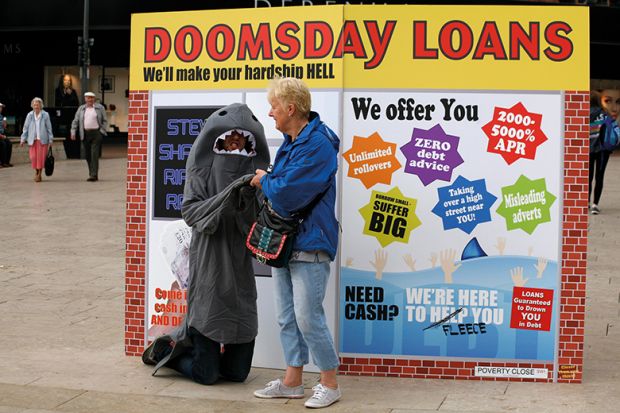

Banks have been called the “hidden regulator” of the sector, with staff at universities hard hit by restructuring accusing leaders of prioritising appeasing lenders over their employees.

Unions at the University of East Anglia – whose accounts last month revealed that it had drawn down £25 million from an existing revolving credit facility – have said they view their institution’s latest round of job cuts as being driven by the need to secure future loan agreements.

Dr Brackley said it was difficult to get a full picture of the types of covenants attached to bank loans for universities, but most were cash flow-related, with declines in international student numbers among the factors negatively influencing banks’ views of institutions.

A breach of a covenant can allow a bank to change the interest rate attached to a loan or, in extreme cases, recall the debt in full or seize the assets of a university.

Such consequences leave universities little choice but to prioritise meeting covenants, said Dr Brackley.

“When they have lenders breathing down their necks, it takes away any time horizon, makes things very urgent. Strict covenants and a weak balance sheet position mean a lot of institutions suddenly in trouble don’t really have any fallback or leeway.”

Alongside more structural debts, universities routinely have to negotiate with banks for arrangements such as revolving credit facilities, which universities use to manage fluctuations in their outgoings over the course of a year. Even universities in good financial health will find these “come at a higher price”, Mr Rabone said, which could affect institutions’ liquidity.

But, he believed, only in “extreme cases” would refinancing prove to be impossible or would universities decide that borrowing came at too high a cost, meaning it will continue to be an important feature of the sector.

后记

Print headline: ‘Wall of debt’ spurs banks to tighten loan terms