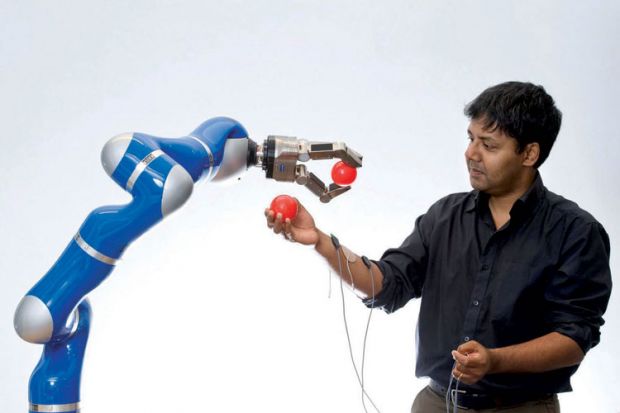

Sethu Vijayakumar’s office looks reassuringly like how you would expect the office of a professor of robotics to look. Scattered around the desk are little robots that loosely resemble Transformers toys, and around them is a selection of mechanised prosthetic hands and limbs.

As co-director of the new Edinburgh Centre for Robotics, a collaboration between the University of Edinburgh and Heriot-Watt University, Professor Vijayakumar is clearly in his element.

As a child, if there was something mechanical, he wanted to find out what made it move. Trained in maths and physics, he considered going into statistics or computing, but robotics won his heart.

“In robotics, you can tangibly see and test the hypothesis you’ve been developing, on real-world solutions,” he said. “It’s things that move and sense, and that’s my fascination.”

Professor Vijayakumar’s fascination is now a government priority: robotics and autonomous systems have been named among the “eight great technologies” and are receiving funding in the hope that they will drive UK economic growth.

Bringing Heriot-Watt’s traditional strength in engineering and links with industry together with Edinburgh’s expertise in informatics and artificial intelligence, the centre (which opened in September) will be a key part of this initiative.

The centre and its doctoral training programme were funded by a total of £13.2 million from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, plus industry support.

The aim is to create one of the world’s leading centres for robotics, and Professor Vijayakumar argued that reaching a critical mass will be crucial to achieving that aim. “In many research areas, you can test and do simulations, and one person can make significant progress,” he said. “[But] this requires collaboration and equipment.”

As robotics technology becomes more advanced, its potential applications are vast. Among other things, the Edinburgh team is working to develop more sophisticated sensor and navigation technology for robots that work alongside people in settings such as warehousing. Currently, robots tend to work in segregated areas and will freeze if they encounter an obstacle, reducing their efficiency.

If this technology is improved, they could work alongside humans – and this is the same sort of technology that could eventually give rise to wider use of driverless cars.

Other applications for robotics include the development of joints with variable stiffness, for use in the generation of wind and tidal power, and the creation of an exoskeleton to assist in physiotherapy programmes, Professor Vijayakumar added. Nanorobots in our bodies that release medicine or address changing glucose levels are equally possible.

However, he said that it was difficult to predict precisely where robotics will go next, likening it to the development of mobile phones: a decade ago, before smartphones, few would have predicted that the devices would come to play a ubiquitous role in our lives.

The range of potential applications serves to emphasise the wide range of skills needed for a career in robotics – including the core sciences and maths, alongside programming and mechanical engineering. This is where the centre’s doctoral training programme, which hopes to attract 60 to 70 students over the next five years, comes in. The intention is to cement students’ knowledge in all these areas while giving them more focused expertise.

Professor Vijayakumar acknowledges that many potential applications throw up ethical questions about the role of robots and their interaction with humans. There are also more practical issues – for example, if a driverless car is involved in an accident, who should be held liable?

Professor Vijayakumar said that these are important issues but cautioned against making sweeping judgements. Using drones as an example, he pointed out that improvements in technology will make them much safer to use around other aircraft over time. “[Ethical debates] need to constantly evolve as things develop,” Professor Vijayakumar said.

One thing he was clear on was the need for sustained funding for robotics in the UK, arguing that the initial investment in Edinburgh is only the start. “This is a revolution that’s happening. If it doesn’t happen here, it will happen somewhere else, and it’s hard to catch up because technology moves so fast.”

In numbers

£13.2m funding received by the Centre for Robotics

Campus news

University of St Andrews

Ann Gloag, the co-founder of transport company Stagecoach, has donated £1 million to the St Andrews-Malawi Global Health Implementation Initiative. The funding will support research into maternal and child health in Malawi and the launch of a new master’s in global health implementation. There will also be a joint PhD programme, in collaboration with Malawi’s College of Medicine.

Aberystwyth University

A new environmental science campus will focus on food security, health and bioenergy. The Aberystwyth University project got the green light after it secured £20 million from the European Regional Development Fund. The plans include a seed “biobank”, a bio-refining centre and a “future food centre”. The campus will cost more than £35 million, with £12 million already pledged by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Kingston University and St George’s, University of London

The effectiveness of hospital ward rounds is to be examined in a £450,000 study. While the report of the Francis Inquiry into the failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust recommended hourly or two-hourly rounds to ensure contact between nurses and patients, medics from Kingston University and St George’s, University of London will analyse whether the practice actually improves patient care.

Queen Mary University of London

Two engineering laboratories will be built at a London university after it was awarded a £5 million grant. A teaching laboratory with space for 80 students and a robot-equipped laboratory for 25 students will be created at Queen Mary University of London thanks to the award from the Higher Education Funding Council for England, which will be matched by the university. The new facilities at the university’s Mile End campus, in East London, are set to open in 2016.

Coventry University

Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, has highlighted a university’s research into the role played by religious groups in preventing violent conflict. The archbishop cited Coventry University’s “faith-based conflict prevention” project as an effective way to promote peace during a House of Lords debate on soft power and non-military options in conflict prevention. The Economic and Social Research Council-funded project is exploring “how churches and faith groups can help spot early signs of violence and stop it from happening”.

University of Buckingham

A new massive open online course about Stonehenge has been developed by the University of Buckingham. More than 1,000 people have signed up to the course, which will start on 21 January and will give students a better understanding of the historic monument. Over the eight-week course, learners will consider what Stonehenge means to them and why it was built, as well as exploring related art, literature, music and architecture.

The Open University

The Leverhulme Trust has awarded a major grant to The Open University to fund research into improving access to education worldwide using new technologies. The £1 million grant will fund 15 full-time, three-year doctoral scholarships over five years. In addition to this, The Open University will fund three scholars from low- and middle-income economies.

University of Brighton

An academic has led a team of experts to create a new set of guidelines to help in the fight against Ebola. Huw Taylor, professor of microbial ecology at the University of Brighton, headed a panel that developed the emergency measures designed to stop the virus spreading in healthcare facilities. The guidelines on sanitary practice are informed by research from Brighton’s School of Environment and Technology on low-cost ways to disinfect human waste during outbreaks.