Source: Getty

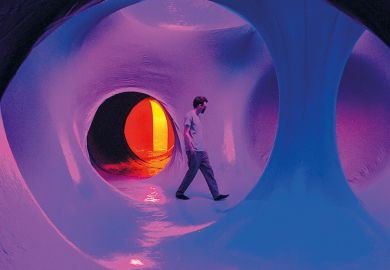

Fresh strings to their bows: music graduates are starting their own ensembles as work for orchestras is harder to come by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart left his job as court musician in Salzburg because it didn’t pay enough and took to the stage to promote his own concerts. Igor Stravinsky made small variations to his works so that he would retain the copyright (and the resulting royalties), and made still more cash by selling some of his work to a player-piano company.

Now music departments at US universities are trying to encourage a similar entrepreneurial spirit among students by adding instruction in business and career support for graduates who face diminishing demand for classical musicians in traditional workplaces such as symphony orchestras.

It is a small example of how US higher education is being forced to show returns on the ever-growing investment being made in them by students and their families.

“This is a little bit of market-side pressure,” said Conrad Kehn, a composer and musician who teaches at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music.

“Career-development programmes are springing up all over music schools,” said Mr Kehn, who in addition to teaching and writing music holds an MBA, directs his own ensemble and is a visual artist.

“I’m not sure people felt we had any obligation to do that in the past. We would teach them how to play and shove a little theory and history into them, and then we’d pat them on the back and say: ‘Good luck.’ But those days are gone.”

The most visible evidence of the change is a centre at the University of Rochester’s prestigious Eastman School of Music that will carry out research into career options for classically trained musicians.

The centre is being launched with a $1 million (£650,000) gift from philanthropist Paul Judy, a trustee of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

“There’s a realisation that most of our music schools and conservatories do a first-rate job of training young musicians in the artistic and theoretical aspects of music, but we have a long way to go [in] jumping the gap into the real world of music economics,” said the school’s dean, Douglas Lowry.

“In the more traditional realms of, for example, the symphony orchestra, the business models are under serious challenge. But our experience has shown that the value of a high-quality music education has applications in lots of different domains.”

Dr Lowry added: “We’re trying to get [students] out of the clouds from time to time so they can at least be exposed to what it means to, for example, understand this rapidly expanding world of internet marketing, driving traffic, creating an audience, and learning what it means not just to be an artistic leader, but a business leader also.”

Ageing audiences, shifting tastes and cuts in government arts funding have taken their toll on symphony orchestras in the US.

A budget shortfall forced the Minnesota Orchestra to cancel part of its season this year. Symphonies and their musicians have clashed over pay and other issues in Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, Richmond and Spokane. And the Honolulu, Louisville, New Mexico, Philadelphia and Syracuse symphonies have all filed for bankruptcy since 2008.

Healthy transformation

Yet despite the gloom and doom, enrolment in music programmes at all levels has not diminished – it has actually increased, from 97,422 nationwide in 2003 to 111,461 this year, according to data from the National Association of Schools of Music.

Many graduates are starting their own ensembles, which have built audiences by performing in small and non-traditional venues including clubs and art galleries.

“The concert hall is no longer the sole domain of classical music,” Dr Lowry said. “This burst of activity in new ensembles is presenting music in whole new ways. Classical music is, in fact, pretty damn healthy: it’s just transforming.”

That is one reason why, despite the dire mood music, unemployment is only slightly higher for new music graduates – 8.6 per cent – than for their peers in general (7.9 per cent) and lower than that for other majors in the arts (9.8 per cent), according to data from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

“These arts students are bright,” said Karen Moynahan, associate director of the National Association of Schools of Music. “Think about the dedication that it takes to be an artist: years and years and years of conscientious study. A student who has the propensity to work at their craft is going to be open to life in general and doing things…that he or she loves.”