In a dusty store cupboard in Stellenbosch University in South Africa’s Western Cape, a doctoral researcher in anthropology recently discovered a slim metal tray full of what looked like human eyeballs.

The tray of glass eyes, each of which had different-coloured irises, sat inside a worn cardboard box alongside a human skull thought to be that of a woman of mixed ancestry and another metal box containing 30 differently coloured locks of human hair.

The artefacts, it was immediately clear, had been used to measure and classify physical differences between human beings of different ethnic origins.

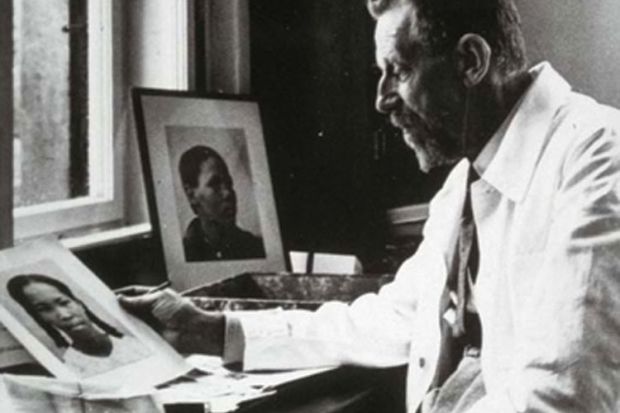

An inscription on the back of one of the eyes revealed their origin: they were the tools of Eugen Fischer, a notorious German eugenicist and Nazi whose theories inspired Hitler.

In the sun-dappled courtyards of Stellenbosch, which for nearly 150 years has been the intellectual heart of Afrikaans language and culture, the discovery in February this year has uncovered a history that some would prefer to forget.

As the PhD researcher Handri Walters and her colleagues subsequently established, use of the instruments was not confined to the 1920s and 1930s, when eugenics was a respectable science studied on campuses around the world. In Stellenbosch, it seems, Afrikaans-speaking scientists used the Fischer tools even as the full horrors of Nazism were being unearthed in the 1950s and 1960s and by which time his theories had fallen into disrepute.

As such, the grisly tray of eyeballs casts an unwelcome spotlight on the university’s links with apartheid.

Preliminary research by Walters and others in Stellenbosch’s department of sociology and social anthropology has established that the Fischer tools were used to teach volkekunde, an Afrikaans variant of cultural anthropology that was studied at the university from 1926 until the mid-1990s and whose leading lights provided much of the intellectual support for apartheid.

Walters’ co-supervisor, Steven Robins, a professor in the department of sociology and social anthropology, explains that Stellenbosch’s volkekunde students used a textbook written by Fischer up until the 1950s and 1960s, long after the international scientific consensus on race had shifted. Robins adds that “it is quite possible that the eyeballs were being used post-war”.

Stellenbosch’s vice-chancellor Russel Botman, the university’s first black leader, has given his blessing to a five-year research project, co-led by Robins and titled Indexing the Human, that will investigate the significance of the find. To do other-wise, says Botman, would be a dereliction of “a moral duty”.

Backlash

But even as Robins, Walters and colleagues set out on their journey of discovery, they have already experienced a backlash in South Africa’s Afrikaans-language media.

There is anger at the suggestion that volkekunde’s academic proponents may have been motivated by racial hatred and outrage at the argument that apartheid could have drawn inspiration from Nazism.

“Our research still needs to be done,” says Robins. “But what is interesting is the response just to the idea that these objects were here and were used at a particular time. It has generated a lot of defensiveness from former volkekunde scholars as well as the wider Stellenbosch community, including former professors and those who went to this university.”

Drawing on Christian Nationalist notions of “morally inferior peoples” and purportedly “scientific” ideas of racial purity, apartheid was the theoretical underpinning of a white-controlled state.

The Afrikaans word “apartheid” literally means “the state of being apart” and for years it was claimed by the regime that South Africa’s racial groups lived “separate but equal” lives.

Today, 19 years after the country’s first non-racial, democratic elections, the oppression and iniquities of the apartheid era are universally condemned in South Africa.

But even now it is not uncommon to hear support for the central tenet of apartheid that people of different “races” should live more or less separately from one another in order to preserve their unique cultures.

Among the critics of Stellenbosch’s attempts to understand the Fischer eyeball and hair trays are those who argue that to try to connect apartheid to Nazism is to make a false equivalence between the two.

Furthermore, the critics argue, to associate “racial science” with apartheid is to apportion unfair blame to the volkekunde scholars whose work was, they claim, misused by racist politicians.

Journalist and former Stellenbosch academic Leopold Scholtz, writing in a recent article in the Afrikaans-language daily newspaper Die Burger, calls the Stellenbosch research project merely “the umpteenth attempt to link Afrikaaner nationalism and apartheid with Nazism”, adding that “black and white does not exist in life; only shades of grey”.

Scholtz goes on to say of Stellenbosch’s vice-chancellor: “Botman and I are both academics, and people like us have an extra obligation to seek the truth with open eyes…Too much emotion clouds the truth.”

Rebuilding ‘cradle of apartheid’

Although Stellenbosch is South Africa’s second-oldest university and has an enviable reputation for research, it still labours under the shadow cast by its reputation as “the cradle of apartheid”.

Hendrik Verwoerd, who as prime minister in the 1950s introduced the first apartheid laws, studied here. He appointed former Stellenbosch volkekunde student Max Eiselen as secretary of state for native affairs. Together, the two Stellenbosch alumni drew up the “high apartheid” policies of racist oppression.

However, Stellenbosch was barely mentioned by Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which dealt primarily with personal criminal wrongdoing during apartheid, rather than institutional culpability.

Since the advent of democracy in 1994, Stellenbosch – like all of South Africa’s elite, formerly whites-only universities – has made slow progress in overturning a massive racial imbalance.

Against the backdrop of a country in which just under 9 per cent of the population is white, 65 per cent of Stellenbosch’s nearly 28,000 students are white. The university says it hopes to reduce that proportion to 50 per cent by 2018 and recently elected to modify its “Afrikaans first” language policy to become a bilingual Afrikaans/English institution.

Work by Robins and his colleagues on the Fischer tools is an attempt to unravel the volkekunde department’s role, if any, in apartheid.

Robins acknowledges: “There is a point to the criticism [of the suggestion] that Eugen Fischer had enormous influence over the formation of apartheid. He didn’t. In fact, his ideas percolated internationally. But in South Africa they took on a particular form.

“The history of human sciences at this university hasn’t really been studied. There’s a lot more to be done. It’s a matter of accounting for the past and trying to think through the way forward. There may be important ethical lessons about the production of knowledge,” Robins observes.

Farewell to the laager

In a recent article in the Rapport newspaper, Botman threw his weight behind the research project.

Addressing the Fischer eyeball find directly, he writes: “The researchers say they consider it their moral duty to pose critical questions about the context, focus, relevance and legacy of conducting science at their institution. I agree. We look our past squarely in the eye; similarly our future.”

He continues: “As at key moments in the past, Stellenbosch University finds itself at a crossroads. We have long since left the laager [a defensive circle of wagons]. We need to keep our momentum and face the future confidently.

“May Stellenbosch become more relevant, diverse, inclusive, welcoming, innovative, entrepreneurial, adaptable, fair for all – as it must be to remain a leading 21st-century university in Africa.”

But the controversy over the find at Stellenbosch shows that in South Africa, coming to terms with the past is still a fraught process.