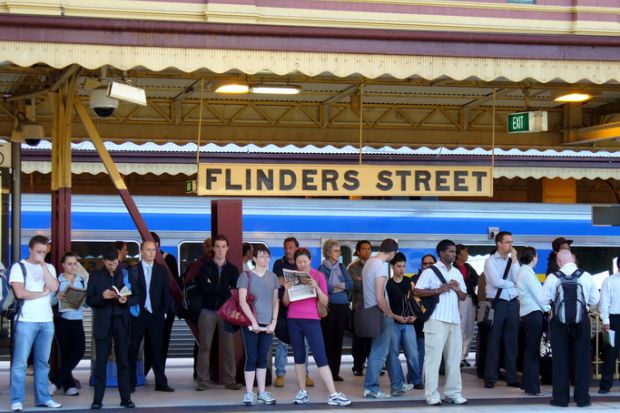

Younger graduates in Australia have seen the extra money they can expect to earn for having a degree fall over the past decade, as the proportion working in graduate-level roles declines, a new analysis suggests.

According to the Grattan Institute’s Mapping Australian Higher Education 2018 report, the average salary premium that a 25- to 34-year-old graduate was earning compared with a school-leaver without a degree fell 6 per cent for men and 8 per cent for women from 2006 to 2016.

Male graduates aged 25 to 34 actually saw their earnings fall in real terms over the period thanks to fewer working full-time and in particular a drop in numbers working in graduate-level jobs.

This fall affected graduates in every discipline except education, nursing and medicine, with science graduates among the worst affected; the share of early career science graduates working in professional or managerial roles fell from 68 per cent in 2006 to 59 per cent in 2016.

For women with degrees, earnings went up 4 per cent in real terms in the 10 years to 2016 but the median income for school-leavers went up by more (10 per cent), therefore eroding the premium, according to the report.

Earnings for women rose across the board thanks to better maternity leave policies enabling more to stay in work after having children, it says. However, the squeeze on graduates in most disciplines finding professional roles also affected women over the decade.

The report says the fall in the graduate premium is likely to affect the “lifetime earnings advantage of holding a bachelor degree” in Australia, although it stresses that the average female graduate is still expected to earn A$600,000 (£330,000) more than a school-leaver over the course of a career, with men expected to earn A$800,000 more.

Meanwhile, the report also points to “surging student enrolments” between 2009 and 2015 – because of Australia’s demand-driven system, which in effect uncapped student numbers – combining with economic downturns to hit the number of recent university leavers being able to find graduate-level roles.

Andrew Norton, higher education director at the Grattan Institute, said that “with or without the demand-driven system, graduate opportunities would have decreased. This was mainly due to the end of [Australia’s] mining boom.

“But extra completions from demand-driven funding made graduate employment rates worse than they would have been otherwise.”

However, he added that the worst of the downturn in graduate opportunities was “now over”, with professional jobs for under-25s up by 23 per cent since a low point in 2014. “By historical standards it is still a tough labour market for young graduates,” he added.

Mr Norton said that for 25- to 34-year-olds “there was never any year-on-year absolute decline in professional jobs. But there was a period of slow growth, making it hard to absorb additional graduates.”

Meanwhile, the report also suggests that the lifetime earnings gap between male and female graduates has narrowed over the period thanks to the boost in income for women as more stay in employment.

“Another factor is that women are over-represented in fields such as nursing and teaching, which increased their earnings while many other disciplines had reduced earnings, mainly due to fewer graduates having jobs that used their skills,” Mr Norton said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view