The release by the UK’s Department for Education of data on graduate salaries by university and subject has long been seen as having the potential to be a game-changer in terms of higher education policy.

Revealing that some graduates earned less after five years than the average young worker who left school at 16 was always going to be politically controversial. And that is even before assessing what the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) data show about the gender pay gap between graduates or the wide variation in earnings potential between subjects.

But the sheer complexity of the data, and the endless caveats and explanations they throw up, arguably raises a much more important question: can policy really be formed on such raw statistics?

A good starting point to answer this question is to examine the data alongside the main piece of contextual information provided with the release: graduates’ exam performance before going to university.

There is a good reason why these contextual data were released: although they only cover England and those who took A levels, they still demonstrate that there is a clear link between what is known as “prior attainment” and graduates’ later earnings, regardless of what university they went to.

But as well as showing this link, the data also allow a deeper analysis to extract examples of where a selective university’s graduates have earned less than might be expected and vice versa.

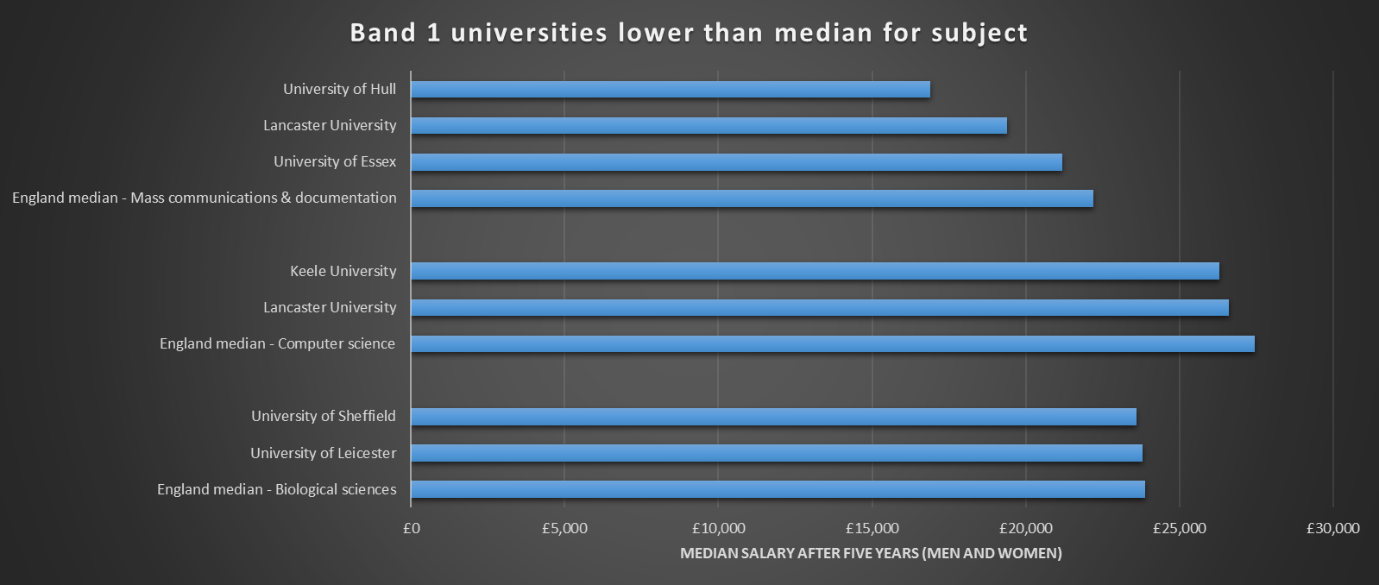

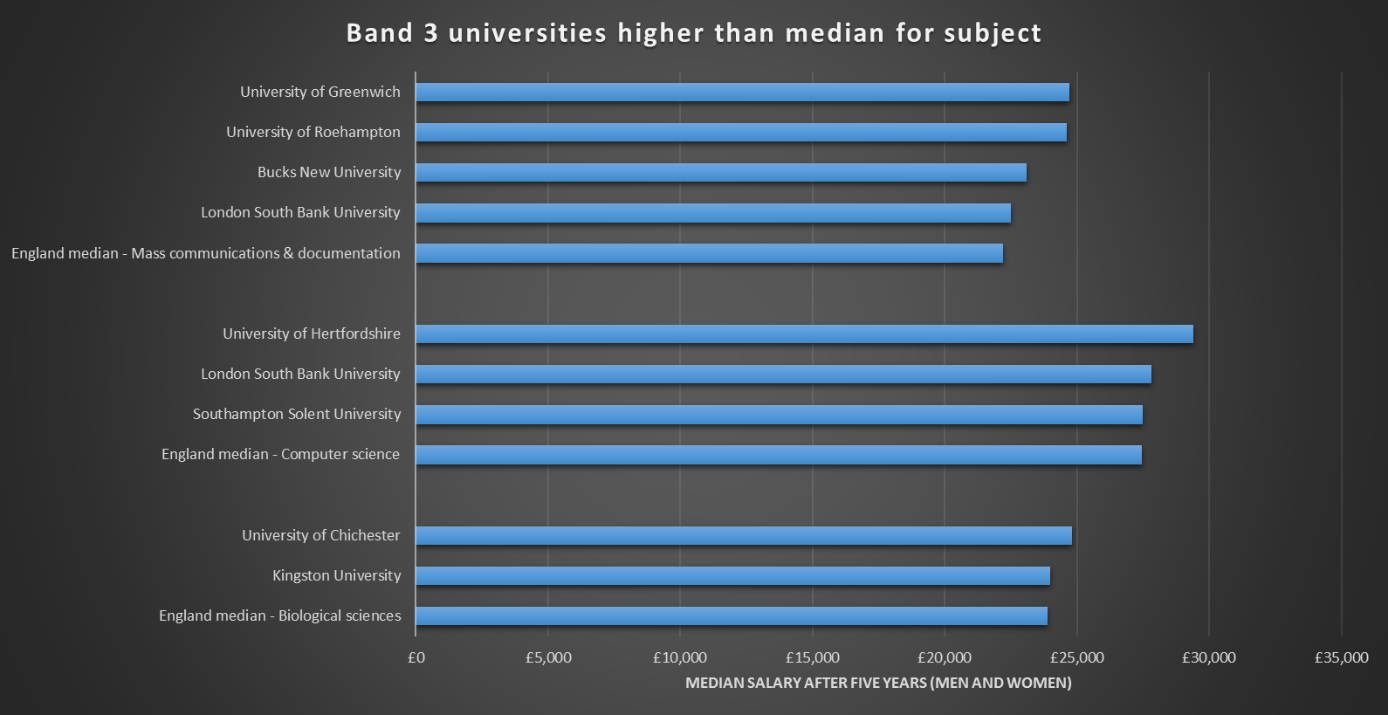

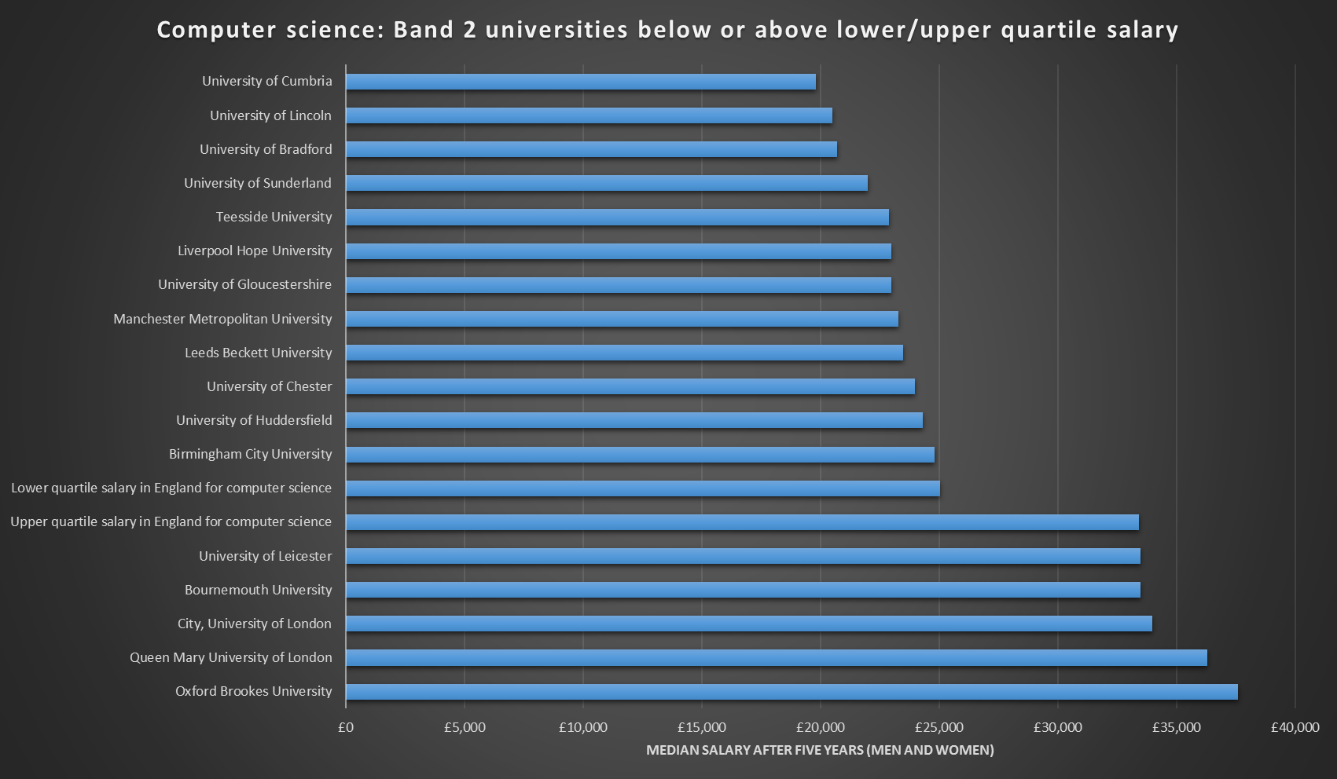

LEO groups prior attainment for each subject area into three bands. Band 1 includes universities that admitted the top 25 per cent of A-level students. Band 2 covers the middle half of institutions (a much wider band) in terms of A-level attainment and Band 3 is the bottom quarter.

Comparing the median salaries after five years for each band with average earnings across all English universities does appear to reveal whose graduates entered higher education with lower grades but still went on to earn relatively high salaries. Conversely, it also shows the institutions whose graduates earned less than average despite leaving school with top grades.

In some subject areas such crossover rarely, or never, occurs: notable examples include law and finance-related subjects such as economics. But the analysis shines a light on universities that do buck the prior attainment trend elsewhere, especially those that do it repeatedly. For example, in six different subject areas London South Bank University produces graduates that earn more at the median than average despite admitting those with the lowest grades. On the reverse side of the coin, Lancaster University has six subjects where its graduates earn less than average after five years, despite admitting those with the highest A-level grades.

The charts below show some examples of three subject areas and the universities from bands 1 and 3 whose median graduate earned below or above the average for the whole of England after five years.

What stands out immediately is that, by and large, there is a North/South divide in the location of the universities. This theme is even more apparent when looking at universities in Band 2 for computer science, where graduates earn above or below the upper and lower quartile earnings for the whole of England (see chart below).

By allowing for prior attainment in this way, it helps to illustrate the point that there is another major factor influencing the figures: regional labour market differences.

They might not be able to explain away every university’s performance. For instance, the University of Sheffield’s median graduate salary falls under the average in four subjects, including in two science subject areas (mathematical and biological sciences) – more than any other northern Russell Group university – despite being a Band 1 institution.

But regional pay factors clearly play a role and it demonstrates that any fair analysis of the LEO data as a measure of performance is difficult, if not impossible, especially given that countless other factors need to be weighed into the mix.

These include the male-to-female ratio of graduates (more women in a subject area would skew the figures, given the evidence that there is a graduate gender pay gap), the types of courses within subject areas (for instance, social studies covers both vocational courses such as social work and degrees such as politics) and the fact that the figures do not include the self-employed.

For Anna Vignoles, professor of education at the University of Cambridge, who is working on a major project led by the Institute for Fiscal Studies to analyse the LEO data against a range of contextual factors, it is a forceful reminder that using graduate salary data to measure teaching quality is seriously problematic.

Most topically, this raises questions about how they could be used in England’s teaching excellence framework (while not part of the TEF this year, LEO is set to inform the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s new-look Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education survey, which feeds into the TEF).

“[LEO] shows that there is a relatively high correlation between prior attainment and eventual earnings…and so [these data] may not be a measure of teaching or university quality in any way,” Professor Vignoles said.

“That does not mean that students shouldn’t know about it…But you wouldn’t want to use it as a simple metric to judge institution quality on the TEF.”

The UK government’s recently published Longitudinal Education Outcomes project, another big data approach, also highlights clear correlation between school attainment and earnings, although this varies between subjects. In subjects such as business, law, English and history, those who attend the most selective institutions have the highest earnings – but that correlation was weaker in some science subjects, where there are greater numbers of graduates from less selective universities on the higher end of the salary scale.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The countless factors behind graduate pay

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?