Middle Eastern science is showing a "powerful - though patchy - resurgence", with Iran and Turkey leading the way.

A new report by data provider Thomson Reuters, Global Research Report Middle East, also flags up particular strengths in engineering and mathematics.

The region's share of global research papers has doubled in the past decade, but stands at just 4 per cent of the total.

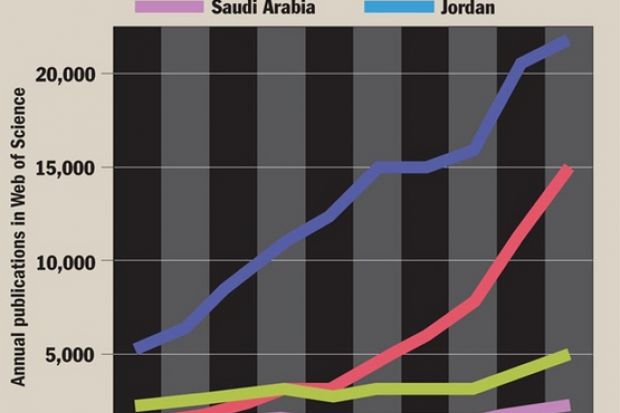

Almost half of that is produced by Turkey, whose output has more than quadrupled since 2000. Iran's research production has also rocketed more than 11-fold in the same period, taking its global share to 1.3 per cent.

These countries, together with Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, produce more than 90 per cent of the region's papers. Israel was excluded from the study.

Current growth is also particularly marked in the United Arab Emirates, and even the region's smallest producers, such as Iraq, Qatar and Yemen, have more than doubled their share of world output between 2000 and 2009.

"These relative changes from a low base are a signal of the huge potential for scientific activity in the region," the report says.

The region's biggest share of world output is in engineering, followed by agricultural science and clinical medicine.

Its lowest share is in social science, but this is growing at the fastest rate. Microbiology, mathematics and computer science are also growing quickly.

The report identifies many pockets of relative research excellence, where the region's percentage of highly cited papers exceeds the world average.

These include mathematics in Iran, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, and engineering in Turkey and Iran. The latter two countries also had the highest percentage of highly cited research overall.

The overall impact of the region's research, assessed by the mean citation count per paper, is also increasing, but remains at about half the world average.

Quantity but not always quality

The report flags up recent initiatives to improve quality, such as the establishment of Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah University of Science and Technology and Qatar's Education City. But it warns that these "will not immediately be translated into world-class research" because it will take time to train a new generation of researchers and to "draw the quality of the new research to the attention of the rest of the world".

It suggests that Middle Eastern countries could also boost their research performance by increasing their number of collaborative projects.

But it notes that the establishment of a regional network of "collaborative endeavour" is compromised by the very low research capacity in some countries.

Mick Randall, an education consultant and the former dean of education at the postgraduate-only British University in Dubai, described the quality of research in the Gulf region as "woefully low" given its economic prosperity.

"This lack of research output rests on the lack of a research culture: a fundamental failure to realise the value of research in social development," he said.

Dr Randall said the region's rulers equated quality with the ability to attract top foreign universities to set up branch campuses.

But he warned that such institutions could not afford to undertake widespread research because companies tended to confine research funding to their own in-house projects, while governments in the region had failed to set up "serious funding councils".

He said that a $10 billion (£6.15 billion) National Research Foundation announced in 2007 by the ruler of Dubai had failed to materialise.

"In the five years I was in Dubai we were unable to find any large-scale funding for educational research," he said.

In the foreword to the report, Ahmed Zewail, the Egyptian-American professor of chemistry and physics at the California Institute of Technology and winner of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, calls on the region to improve education, embrace freedom of thought, boost meritocracy and set up centres of excellence in each country "to show that Muslims can compete in today's globalised economy and to instil in the youth the desire for learning".