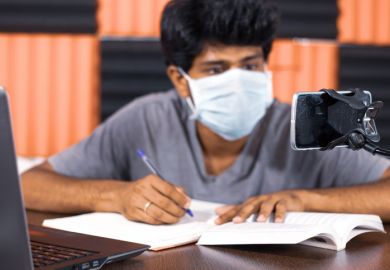

Campus closures in India, the Asian nation hardest hit by Covid, have widened the gap between rich and poor, a seminar heard.

Lower-income, rural and female students were even more marginalised under online learning than they were before, according to Nivedita Sarkar, an expert in education financing at Ambedkar University (AUD).

If students continued to be left out of the system, fewer of them may be willing to resume their course next year. According to research by the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration, enrolments could drop by 17 per cent in the next term in 2021.

It is unlikely that campuses will open fully and safely soon. India, which has recorded more than 9 million total Covid infections, has been on some level of lockdown since March.

“Even before the pandemic, Indian higher education was highly unequal,” Dr Sarkar said during a webinar hosted by the Centre for Global Higher Education. “Then there was this sudden move to an online mode of teaching. And online education exacerbated inequality.”

In the early months of the pandemic, the Indian government greatly expanded free online education tools.

However, among rural students, 83 per cent lack electronic devices and 58 per cent lack internet access, making them far less capable of taking advantage of those resources.

Dr Sarkar said the government had sought a “technocratic solution” to campus closures without consulting fully with stakeholders such as teachers, students and parents. “A solid, systemic response and more government intervention is needed,” she said.

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford and host of the webinar, said: “It’s unfortunate that the country had managed to boost participation in higher education, and then this happened and campuses were shut. This created a type of learning that people can’t access on the scale needed.”

Dr Sarkar also blamed a “highly privatised HE sector” for the gap in access.

In a country where per capita income is $2,100 (£1,650), higher education puts an enormous strain on families, even without a pandemic.

The average household spends 19 per cent of total expenditure on higher education, per child per year. “So if a household has two children, that’s nearly 40 per cent,” Dr Sarkar said.

The richest 20 per cent of households spent 44,219 rupees (£447) on HE, compared with the poorest 20 per cent of households, which spent 11,374 rupees. Not surprisingly, rich households had a much higher gross enrolment ratio of 44 per cent, compared with 11 per cent in the poorest households.

Another major disruptive factor was large-scale job losses, which most greatly affected those aged 15 to 24.

Unemployment, or the shift to low-quality jobs, meant that education “was not seen as helpful in the short run”, Dr Sarkar said. Poorer students might be unwilling or unable to pay more for electronic devices and internet access if there is no immediate hope of a financial pay-off from their education.

“If you are well off, you may be able to take that risk and make that investment in HE,” Dr Sarkar said, but that was not true of poor students. “Many students are dropping out because online learning is just not happening, and their families are unwilling to pay for it.”

Online learning has also exacerbated gender inequality, as female students kept physically at home had to adhere to more traditional roles.

In her own institution, a state university in Delhi, she observed that “98 per cent of female students contribute substantially to household chores, and 40 per cent have no private place to sit and study”.

She expressed a sense of frustration as an educator trying to reach such students digitally. “With audio muted and video off, they become like anonymous beings, and we teachers cannot know their struggles,” she said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?