Higher education programmes for refugees can place unrealistic expectations on student performance and fail to take into account the challenges of their environment, a new study has found.

A paper, based on interviews with 122 refugees who had undertaken a higher education course, revealed that many students felt their programme lacked “contextually based examples” and their professors lacked flexibility “especially with deadlines”. In one refugee camp, the study noted, the “main issue seemed to be a lack of understanding from US-based professors on the challenges faced by students”, in relation to their “ability to access course and study materials, while having to balance family and other responsibilities”.

Some of the refugees interviewed also highlighted concerns about their future after completing the course.

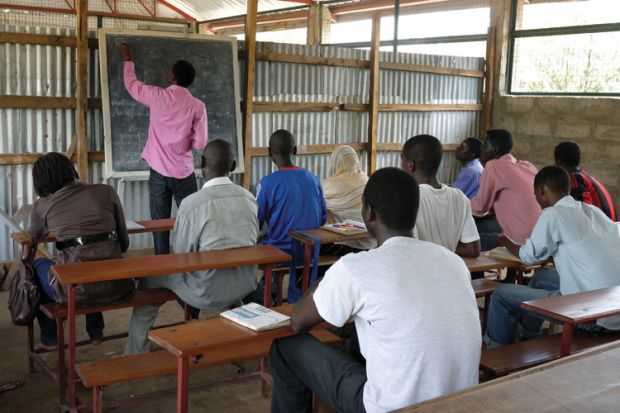

Participants in the study were either current or former students of Jesuit Commons: Higher Education at the Margins, a programme that partners with academics and universities around the world to deliver higher education to those who would not otherwise have access to it. The refugees were based at Kakuma camp in Kenya, Dzaleka camp in Malawi and in Amman, Jordan.

Thomas Crea, associate professor at Boston College’s School of Social Work and author of the paper “Refugee higher education: contextual challenges and implications for program design, delivery, and accompaniment”, said the opportunities offered to refugees were “constrained” due to their environment.

“There are logistical issues of distance from the learning centre and of international instructors not understanding the context of the students very well, and so sometimes having unrealistic expectations of student performance,” he told Times Higher Education.

He added that higher education programmes for refugees should be “linked to the specific context” of their location.

“Instructors could do a survey of the current circumstances in each site, what non-governmental organisations are working there, what possible job opportunities or volunteer opportunities are available and then create a pipeline so that when students complete their coursework they don’t just drop off the cliff but there is something they can do to use their education in a way that’s meaningful,” he said.

Despite the challenges, respondents “emphasized the benefits” of receiving education, expressing “feelings of empowerment” and an “increased awareness and facility with psychosocial and interpersonal skills”. Dr Crea said their experiences of personal growth inspired them to “help and build the communities around them”.

“I was a bit surprised about the strength of that theme across the different focus groups,” he added. “When you ask generally ‘what are the benefits of education?’, you expect it will be related to learning content or critical thinking or skills development. There was a lot of that as well, but there was also a sense of hope.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Courses for refugees lack ‘context and flexibility’

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?