Researchers in the UK are extremely productive, but the country may need some "innovative solutions" to maintain its global position in a harsh funding climate.

That is the conclusion of a report by the 1994 Group of universities that compares the UK's research output with that of the US, Australia, Germany, Japan and China.

Mapping Research Excellence: Ex-ploring the Links between Research Excellence and Research Funding Policy draws on data from the Or-ganisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and Elsevier's SciVal Spotlight citation comparison tool to show that the UK has the most areas of research excellence - described as "competencies" - per researcher and per national spending on research and development.

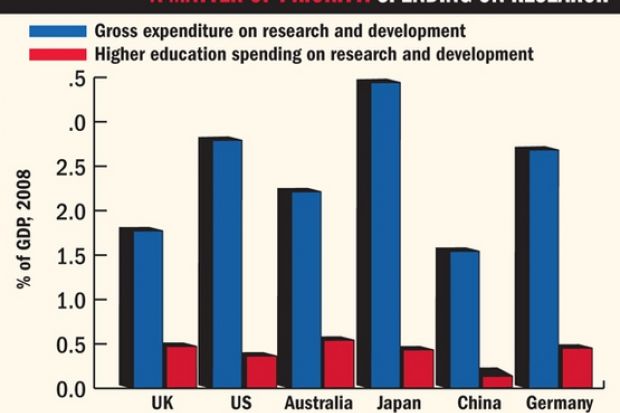

According to the report, launched on 29 September at the fifth UK Research Conference in London, the UK's gross expenditure on research and development in 2008 was $40 billion (£25.9 billion), compared with $19 billion in Australia, $82 billion in Germany and $398 billion in the US.

The UK figure amounted to just 1.77 per cent of gross domestic product. Only China recorded a lower proportion, while Japan had the highest, 3.44 per cent.

The UK's research-intensive universities - which are defined as members of the 1994 and Russell groups - account for 92 per cent of the country's research competencies.

That figure is similar to those for comparable institutional groupings in the US and Australia, countries that also have largely competitive funding systems.

The report suggests that such systems boost productivity because "through the policy of rewarding excellence wherever it is found, funding follows excellence in a responsive way settling at a natural, not predetermined level of concentration at research-intensive institutions".

Higher education spending on research and development as a proportion of GDP is highest in Australia and the UK, where, the report suggests, productivity is boosted by a "well-supported higher education sector and an underlying core of government support for research".

Paul Wellings, chair of the 1994 Group, vice-chancellor of Lancaster University and one of the authors of the report, highlighted the disciplinary breadth of competencies in the UK sector, which was rivalled only by that of the US.

"That gives me some solace when thinking about the growth and innovation agenda," Professor Wellings told Times Higher Education.

"It tells me that we are pre-adapted as a university system to engage around where emergent business and industries might be."

However, the report notes that the UK, like the US, has a relatively low proportion of competencies in which its global share of journal articles is expanding.

"This, combined with one of the lowest proportional rises in research and development spending ... may be a warning signal for the UK," it says.

With an increase in research spending unlikely, it suggests that the UK may have to "look to innovative solutions" to maintain its global position. Professor Wellings said it was important to ensure that the UK expanded competencies in "rapidly growing areas".

If the research councils were intent on channelling funding into thematic areas, he said, it was imperative "to make sure there is proper policy dialogue around that - rather than a wet finger in London saying: 'Let's invest in nanotechnology'".