Australia’s biggest regional university has credited government largesse and “tough” decisions for its surprise 2020 surplus.

Charles Sturt University (CSU) notched a A$19.5 million (£10.6 million) operating result last year, effectively doubling its 2019 buffer of A$9.8 million, according to a report from the New South Wales (NSW) auditor-general.

CSU was the only public NSW university not to have its annual report tabled in state parliament in May, fuelling speculation that its financial situation had deteriorated because of the pandemic and other problems.

But the delay was caused by technical reporting errors, after CSU failed to record two capital grants – one for expansion of its Port Macquarie campus and another for student accommodation – as revenue. While new accounting standards excuse universities from reporting one-off grants until they have spent the money, this does not apply to capital funding.

The error has now been resolved, adding A$34.5 million to CSU’s bottom line and reversing pre-Covid projections that the institution faced a A$16.2 million deficit – a prediction later revised to A$49.5 million, as the pandemic took hold.

Interim vice-chancellor John Germov said that if one-off grants were disregarded, CSU had spent A$15.5 million more than it earned last year. But he predicted a “balanced budget” by the end of 2021.

The auditor-general’s report shows that in proportional terms, CSU reduced its expenses by more than any other NSW university while attracting the biggest boost in government funding. Professor Germov said the university had lost almost 200 staff and cut most capital works spending along with “discretionary” expenses such as travel.

“We reviewed our course profile and made some tough decisions about ceasing unpopular offerings where there had been declining student demand, and the courses or subjects within them were no longer viable,” he said. CSU had also benefited from increased postgraduate enrolments and short-course funding.

Professor Germov also highlighted other “positives” in the report, with this year’s first semester domestic enrolments up 5 per cent on last year. CSU has also become the state’s top educator of Indigenous students with more than 1,200 enrolments.

Such achievements coincided with regulatory and leadership difficulties. In early 2019, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (Teqsa) banned CSU from accepting new students at capital city centres run by a private partner.

Teqsa revoked the ban after CSU persuaded it that extra “controls” had been put in place to safeguard academic integrity and quality, but the university was registered for only four years instead of the customary seven and incurred additional requirements.

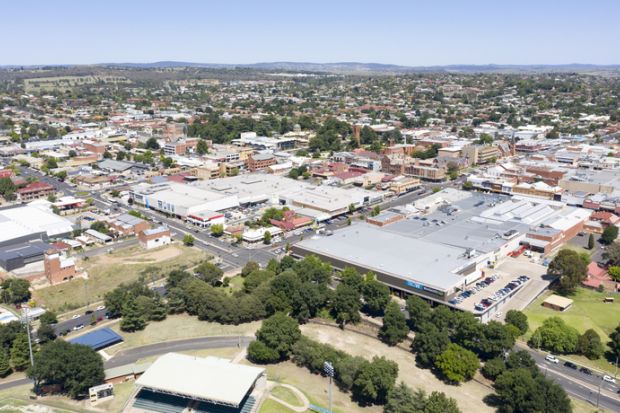

CSU also lost vice-chancellor Andrew Vann in unusual circumstances last year while enduring a public brawl with regional education minister Andrew Gee, whose electorate covers the university’s Bathurst and Orange campuses.

In October, Teqsa revealed that it was investigating CSU’s financial status, on request of then education minister Dan Tehan. “There is something problematic about the governance at CSU, given everything going on there in the last 12 months,” said Damien Cahill, NSW secretary of the National Tertiary Education Union.

Professor Germov said the university had met all of Teqsa’s requirements. “We’ve tightened up our oversight and governance procedures, including rewriting our whole academic policy suite, re-crafting our governance committees’ terms of reference and membership, and also introducing very thorough student performance outcome reporting and consideration by our academic senate. I think we are a stronger institution for it.”