Scaling back humanities and social science degree provision in Japan may hamper the country’s efforts to internationalise its academy, a senior university leader has warned.

Adrian Pinnington, dean of Waseda University’s School of International Liberal Studies, said that Japan’s ambitions to attract more foreign students and academics could be severely damaged if ministerial pressure to reorganise universities led to the closures of humanities and social science faculties.

These departments have the best links with Western universities and are crucial to establishing international partnerships at institutional level, said Professor Pinnington, who has taught in Japanese universities for almost 35 years.

“Departments like mine – those doing modern languages, literature, history – are the ones who have the best contacts with overseas academics,” he explained. “They are the ones who have done the most to push forward efforts to internationalise universities and recruit students internationally.”

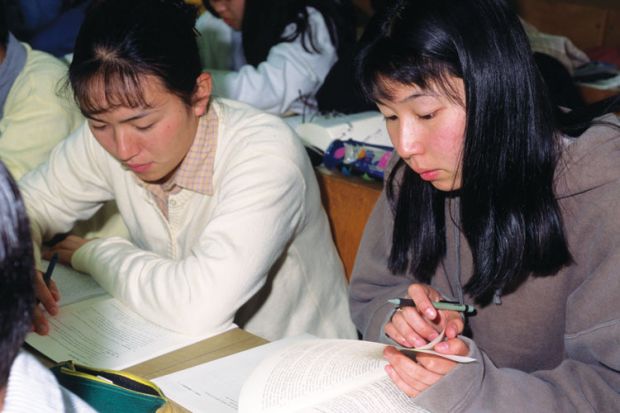

At his own school at Waseda, one of Tokyo’s leading private universities, about a third of its 600-strong intake are international students and another third are Japanese students keen to undertake a period of overseas study, he said.

Top international corporations are increasingly looking to recruit humanities and social science graduates with international experience, rather than scientists, Professor Pinnington added.

“Seventy per cent of our graduates go into top companies,” he said.

Many large corporations had specifically asked for university recruitment fairs to be based at Waseda’s liberal arts schools, he added.

His comments follow a global outcry over a letter sent in June by education minister Hakubun Shimomura to all of Japan’s 86 national universities, which urged them to assess faculties teaching social sciences and humanities.

It recommended that they take “active steps to abolish [these] organisations or to convert them to serve areas that better meet society’s needs” – a directive widely criticised by Japanese scholars from all disciplines.

Japan’s Education Ministry has since insisted that its letter was misinterpreted, stating that it was part of a wider call for institutions to review all aspects of provision, a process that began in 2013.

“The ministry is very concerned about the declining number of 18-year-olds and [having] too much capacity at many universities, particularly regional ones failing to fulfil their enrolment quotas,” Professor Pinnington explained.

“Its recommendation for reforms related to changing demography, but the implication was that funding would be forthcoming for the sciences and technology that demonstrated benefit to society, but not for social sciences and humanities faculties that did not reform,” he said.

“Of course, the ministry was not officially telling anyone to do anything, but simply asking them to assess departments in the face of a considerably changing society,” he added.

Upset within the academy

That message has upset many within Japan’s academy because “the implication was that social sciences and humanities were not as relevant to people’s needs as the sciences”, Professor Pinnington said.

“When you look at the message that we are receiving from employers, this is clearly not the case,” he said.

However, the episode has highlighted how many Japanese universities had been slow to adapt to the country’s demographic challenges, with institutions reluctant to close courses in the face of plummeting student numbers, Professor Pinnington said.

“If applications fall in the US, they will close departments, but that does not happen in Japan as it is not that kind of society,” he said.

Universities hugely valued the notion of consensus among academics and were therefore unwilling to take unpopular decisions on course closures, he added.

“Teacher training programmes are a real problem,” Professor Pinnington said. “Many thousands of teachers are being trained each year, but there are so few vacancies for them as the school-age population is shrinking so rapidly. You might have just one or two teachers from thousands of graduates gaining a job in some regions.”

Academic tenure meant that it was also difficult to remove scholars in areas of weak student demand, he added.

“Japanese universities are trying to find a way to reform while still appealing to students and not losing the many great things about their system,” he said.

后记

Print headline: British dean: reform push will hit global outreach in Japan