The success rate for grant proposals at UK research councils has fallen again despite efforts to weed out weak applications, intensifying the worldwide debate over whether academics’ time is being wasted by ultra-competitive funding schemes.

“Demand management” measures – such as preventing repeatedly unsuccessful applicants from applying for 12 months – appeared to cool off competition during the past decade in the UK, with success rates rising from 26 per cent in 2010-11 to 30 per cent 2012-13.

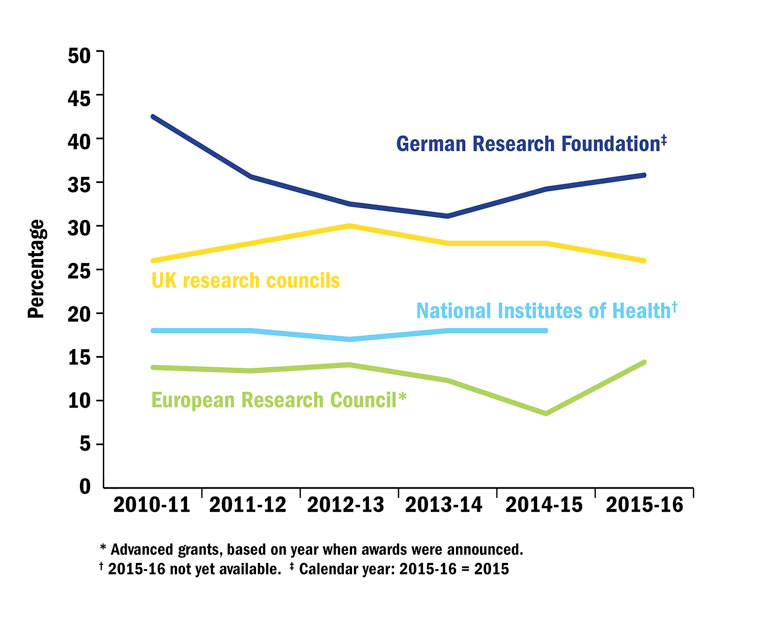

But since then, this progress appears to have been partially reversed, with rates falling back to 26 per cent in 2015-16, according to data compiled by Times Higher Education.

At the Medical Research Council, success rates have slipped by two percentage points to 20 per cent, making it almost as competitive as the National Institutes of Health in the US (see graph).

Sarah Collinge, head of research funding operations at the council, said that this was a result of an increasing number of applications.

With researchers in other countries also facing similarly slim chances of winning funding, some have suggested introducing a cap on applications per university or researcher, or even bringing in a lottery system to prevent academics wasting time on normally fruitless proposals.

International comparison of research grant success rates

A study last year that looked at astronomy and psychology found that it took an average of 171 hours to write a grant proposal. If a funding agency has a success rate of below 20 per cent, researchers should consider abandoning attempts to win grants because of the time that was likely to be wasted, concluded “To Apply or Not to Apply: A Survey Analysis of Grant Writing Costs and Benefits”, published in Plos One.

Co-author Ted von Hippel, an associate professor of physics and astronomy at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, and co-author of a further analysis looking at appropriate success rates released last year, told THE that he believed “the system starts to break down” when success rates drop below 30 per cent.

A report by Research Councils UK in 2006 suggested that a success rate between 20 per cent and 50 per cent represented an “acceptable balance between the benefits of competition and the cost/effort to support the system”.

However, raising success rates could require controversial measures. Elizabeth Berman, an associate professor of sociology at the State University of New York Albany, suggested that the best method could be a lottery system to determine who may apply in a particular funding round.

“Of course, it would eliminate good proposals along with bad, but since research suggests reviewers can’t distinguish among very good proposals anyway, it seems no less random than the present system while involving a lot less wasted work for researchers,” said Professor Berman, who has argued that the grant system is a “tragedy of the commons”.

Such a system would also have the benefit of stopping universities using grant success as a proxy for researchers’ quality in hiring and promotion decisions. Grant-getting has become “a key marker of academic success even when grants are not strictly necessary in order to conduct research”, she said.

Overall UK research council success rates

| Applications | Grants | Success rate (%) | Amount (£) | |

| Arts and Humanities Research Council | 246 | 68 | 28 | 29,851,958 |

| Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council | 1,621 | 392 | 24 | 178,719,000 |

| Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council | 2,417 | 786 | 33 | 509,476,006 |

| Economic and Social Research Council | 429 | 52 | 12 | 24,107,303 |

| Medical Research Council | 1,993 | 402 | 20 | 283,520,000 |

| Natural Environment Research Council | 1,036 | 311 | 30 | 86,871,071 |

| Total | 7,742 | 2,011 | 26 | 1,112,545,338 |

Source: UK Research Councils.

Note: Success rate is by number of applications. Because of rounding, totals may not exactly equal individual research council figures. Some specialist, non-academic and overseas recipients have been excluded, hence success rates may differ slightly from research councils’ stated totals.

Another option is to cap applications by university or individual, she explained. This has been considered in astrophysics, said Professor von Hippel, but he added that it would be “very difficult to fairly implement and would create a lot of grumbling from those kept out of the application pool in a given cycle”.

One measure taken by the European Research Council is to stop researchers from applying for up to two years if a previous application has scored poorly.

The ERC’s president, Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, told THE that getting below a 10 per cent success rate can lead to “some excellent scientists” deciding not to apply. “This is why the ERC monitors this carefully,” he added.

In recent years, the council had also evened out success rates between different grant streams, he said, “giving priority to younger researchers”.

Meanwhile in the US, the leaders of the National Institutes of Health have argued that the ultimate solution to halting the drop in success rates is to end the squeeze on funding.

However, success rates at the German Research Foundation, which in 2015 distributed €886.7 million (£767.2 million) in individual grants, have been climbing since 2013. A spokeswoman said that the organisation does not take any action to limit demand, with “the only criteria of selection” being “scientific quality”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Decrease in UK grant success rates prompts worldwide comparisons

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?