The University of Stirling never used to be coy about its dealings with Joseph Mifsud. John Gardner, the institution’s senior deputy principal, tweeted a photo of him alongside former MP Sir George Reid with the caption “our diplomacy A-team”. But Stirling has clammed up a bit since Professor Mifsud was revealed to be the unnamed academic who allegedly set up meetings between Donald Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos and Russian officials and offered “dirt” on Hillary Clinton. The university refused to say if it would investigate Professor Mifsud, who was, until recently, listed as the honorary director of the London Academy of Diplomacy, which began offering Stirling-accredited degrees in September 2014. Stirling would confirm only that Professor Mifsud had “been a full-time professorial teaching fellow in the university’s politics department since May 2017”. The Maltese academic has denied any wrongdoing, describing Mr Papadopoulos’ claims as “incredible”. From one angle, this is a bit of a shame – because helping to swing the result of a US presidential election would be a great impact case study for the next research excellence framework.

The makers of a Chinese TV show apologised to the University of Nottingham’s China campus after “teachers and students expressed outrage about dialogue that suggested it offered a poor-quality education”. An episode of Hunan TV’s The Road Will Be White from Tonight “featured a character who had studied at the university saying ‘students at the China branch are struggling with their work’ and a joke that implied undergraduates just needed to turn up to get a degree”, the South China Morning Post reported on 3 November. Nottingham, which had given permission for the programme to film at its Ningbo campus, had said that it would seek legal advice before the producers apologised and pledged to “delete any content that mentioned the name of the university”, the newspaper reported. Given that the campus has required Chinese government approval to establish itself, and that the Chinese government is not known for enjoying a giggle at its own decisions, there were plenty of red flags for the producers.

There was trouble at home for the University of Nottingham and Nottingham Trent University after Nottingham City Council sent letters to properties in an area popular with students warning that noise problems were damaging their neighbours’ mental health and family lives. The council “said that it was forced to act by the volume of complaints about house parties in the first weeks of term”, The Times reported on 1 November of problems in the Lenton area of the city. “In one case a party attended by more than 100 students resulted in a wall collapsing. In another, children in a neighbouring house missed school the next day because they could not sleep.” At one meeting with residents, “it emerged that a father left the family home because of the constant noise of parties”, the newspaper added.

Higher education’s blizzard of acronyms temporarily blinded the Higher Education Funding Council for England as it blundered into the somewhat sensitive field of Northern Irish politics by mistakenly adding a paramilitary-linked Irish republican party to a list of groups that could put forward assessors for the 2021 research excellence framework. BBC News online reported on 3 November that Hefce had blamed “an administrative error” for listing the Irish Republican Socialist Party alongside the British Medical Association and more than 2,000 other learned or academic groups that could recommend potential assessors of research. The Northern Ireland-based party has close links with the Irish National Liberation Army, which is believed to have been responsible for at least 120 murders during the Troubles. No other political party appeared on the list. Hefce said that the mix-up occurred after “an organisation with a very similar acronym” was approved for its list of expert organisations.

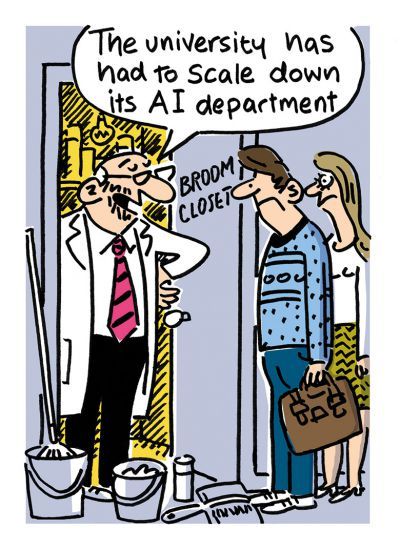

UK universities are suffering a brain drain of artificial intelligence experts to the better-paid private sector, The Guardian reported on 2 November. Based on a survey of Russell Group universities, the paper concluded that scores of computer scientists had left or passed up academic posts for salaries two to five times higher at major tech firms. “This goes beyond the normal exchange of people between academia and industry,” one senior academic told The Guardian, adding that poaching by Google, Facebook and other tech giants risked creating a “missing generation” of academics able to teach AI. While other academics are continually told they are at risk of replacement by robot teachers, it seems this is less likely in AI itself, the report suggests. “We need top-quality staff to teach and research, and the implications of not achieving this don’t need to be spelt out,” one business executive said.