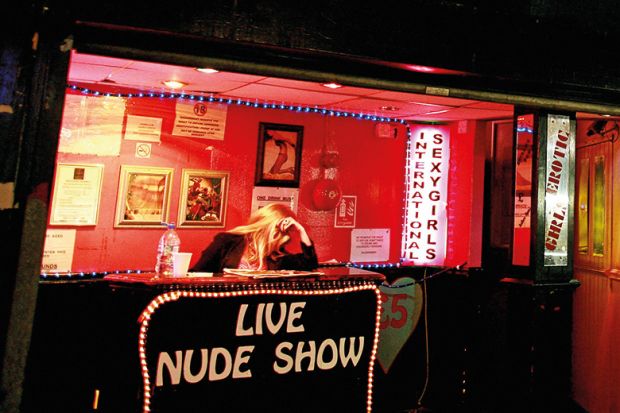

The “whorephobic” attitudes of many UK universities towards students who work as erotic dancers are blocking important research into their experiences in the adult entertainment industry, according to a scholar who has explained how her own studies have been deliberately stymied by uncooperative institutions.

While as many as one in 20 undergraduates may be working in the adult and sex industries, if recent surveys are to be believed, there is relatively little academic research into their lives, in particular whether they remain in the sector after graduation, said Jessica Simpson, who sought to tackle the latter question for her PhD studies at City, University of London.

But Dr Simpson, now a lecturer in sociology at the University of Greenwich, said her attempts to find student strippers to interview were routinely blocked by universities and students’ unions who would refuse her permission to distribute posters or flyers within their premises.

THE Campus resource: Eight ways your university can make research culture more open

“Some universities were more explicit than others about their reasons for not allowing me access, but either way it meant I was repeatedly blocked from advertising my study,” she told Times Higher Education.

“Some universities responded by saying none of their students would be sex workers so I was wasting my time and should try a post-92 university, while others claimed the flyers would have the potential to cause offence to other students opposed to the sex industry, and some said they felt it could be seen as endorsing students who did this job.”

Many universities’ research ethics committees replied, often after a lengthy delay, to say the subject was simply “too sensitive” to allow flyers to be displayed, said Dr Simpson, who eventually recruited 37 respondents for her study, mainly through sex worker collectives. “There was no opportunity for dialogue,” she said.

Students’ unions were equally obstructive to her research efforts, despite many claiming to support students engaged in the sex work industry, added Dr Simpson, who has described the obstacles she faced in the journal Higher Education in a paper titled “Whorephobia in higher education”.

Many objected to the flyers by claiming it would be “inappropriate” to display them on their premises, while several pole-dancing fitness societies also declined to help, as many were keen to “shake off the idea that all pole dancers are strippers”, with one stating that “anyone associated with being a stripper is asked to leave”.

“Given these were the responses to a PhD student, with ethics approval, seeking to carry out a research project, you can imagine the hostility that students engaged in this work face themselves,” said Dr Simpson, whose interviewees told her they had been told to give up their work as erotic dancers or face expulsion on account of “bringing the university into disrepute”.

That sense of institutional revulsion was why Dr Simpson chose the provocative title of her paper, she explained.

“There was a real sense of potential ‘contamination’ when it came to sex workers and a definite attempt by universities to distance themselves, often in a hostile way, from student sex workers,” said Dr Simpson.

Condemning the “paternalistic attitudes” of universities that led them to become “hostile environments” for hundreds of students, she added: “We need to tackle this whorephobia as we have done homophobia or transphobia.”

后记

Print headline: ‘Whorephobia’ blocking research into student sex work, says scholar