Before settling down to write this review I found myself browsing through Northern Irish newspapers. Their headlines spoke of increasing political tensions, socio-economic deprivation and segregation, the threat posed by dissident Republican terrorists and the fallout from the Loyalist flag protests of December 2012. Fifteen years on from the signing of the Belfast Agreement, this book’s subtitle, The Reluctant Peace, is particularly apt.

Feargal Cochrane has set himself a not inconsiderable task - to trace the history of the Northern Irish conflict and peace process and to demonstrate how contested understandings of the past continue to shape the social and political landscape. A further unspoken objective is to add something fresh to the well-trodden terrain of research on the history and politics of Northern Ireland and its transition. He achieves these aims in a thoughtful, engaging style.

Taking a chronological approach, this book weaves its way from the earliest iterations of the conflict to the present day. This is not an aridly scholarly text or one overburdened by policy details. Rather, it carefully draws the reader into the complexities of the conflict and the peace process in a readable and accessible manner. While Cochrane is careful to balance and contextualise, he also offers praise and criticism where they are due. In doing so, he carefully navigates the sensitivities that surround the conflict but also does not spare the reader from the reality of violent conflict and its causes and effects; his discussions of Bloody Friday in 1972 and the 1975 Miami Showband massacre are cases in point. His personal reflections bring humanism and an insider’s view that adds to the richness of this work.

As Cochrane moves into the twists and turns of the peace process, he focuses on the main political actors rather than the finer technical details of the Belfast Agreement or the St Andrews Agreement. The tensions between hope and expectation on the one hand, and the reality of “doing” peace and politics in a divided society on the other, are brought to light. A frequent undercurrent to these discussions is the fragile nature of the process and how the presence of lingering suspicions and hostilities have an effect on the ongoing peace process. One criticism that could be made of Northern Ireland: The Reluctant Peace is that in covering a lot of ground, the final chapter nearly tries to do too much, touching on everything from public attitudes to change, commemoration and dealing with the past and community relations. These are all substantive issues that warrant being explored more fully.

As he emphasises, it is important not to undersell the changes that have taken place in Northern Ireland or to understate the time required to embed peace after generations of violence. Yet his work highlights the many challenges still to be overcome: enduring sectarianism, a lack of progress on developing the “cohesion, sharing and integration” strategy, the politicisation of victimhood and the distance between the “peace dividend” at the level of political elites and the reality of everyday life in those communities most affected by the conflict. Most problematic, as Cochrane notes in the introduction, is the continuing presence of the past in the present. As debate rages over the transformation of the site of the former Maze prison into a centre for conflict transformation, the sobering reality is that conflict has not entirely ceased. Cochrane’s assertion that Northern Ireland needs to “deal with its past in a manner that defuses the incendiary history of conflict” is compelling. The expert, the interested or the simply curious will find much of value in this timely book.

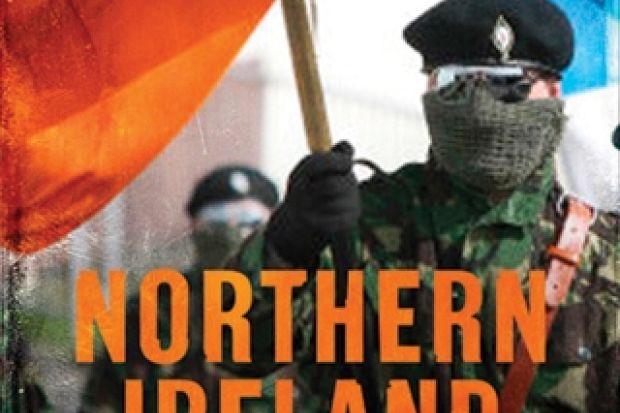

Northern Ireland: The Reluctant Peace

By Feargal Cochrane

Yale University Press, 320pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780300178708

Published 25 April 2013