“Men and women of the Congo: victorious fighters for independence…we are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force. This was our fate for eighty years of a colonial regime; our wounds are too fresh and too painful still for us to drive them from our memory.”

This is an extract from the electrifying and spontaneous speech that the first democratically elected president of Congo-Léopoldville, Patrice Lumumba, gave when the Belgians formally handed over power to the new republic on 30 June 1960 in today’s Kinshasa. He decided, courageously – recklessly possibly – to deviate from the order of the heavily choreographed ceremony, after the Belgian king, in a speech punctuated by gun salutes, declared the Congo’s independence to be “the crowning of the work conceived of the genius of King Leopold II”. King Baudouin called on the nationalists “to show that we were right in trusting you”. Lumumba’s response was roughly translated for him as: “They’re not going to be your monkeys anymore.” The king promptly exited stage right.

Lumumba endeavoured to offer conciliatory speeches later that day, but hell hath no fury like an arch-colonial ruler scorned. In effect, the speech was his death sentence. On 17 January 1961, after months of imprisonment in which he was sadistically burned, beaten, starved and kicked to shreds, he was shot along with other nationalist leaders. Ten days later, their bodies were dug up and chopped into pieces so they would fit into an acid bath.

Emmanuel Gerard and Bruce Kuklick, academics based in Belgium and the US respectively, have bravely taken on the most important and disturbing assassination of a democratically elected leader in modern times, and an event on a par with that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand for the mayhem and madness left in its wake. Their book, seemingly aimed primarily at a student audience unfamiliar with the story and its vast literature, also tries to suggest a new emphasis by reinterpreting secondary sources and trawling intensively through archives, drawing heavily on US State Department, United Nations and Nato records.

“The West”, they argue, “had given its first postcolonial tutorial. Within a month, six other prominent Lumumba supporters were slaughtered.” In the mineral-rich Katanga province, a mutiny was organised against Lumumba and his fiery anti-colonial rhetoric; the UN was used to bring down his government; the Central Intelligence Agency and the Belgians worked together to have him arrested and thrown to the lions once he looked to the Soviet Union for outside assistance. He was handed over to his fierce Congolese opponents, and met a brutal end.

Rather than interpreting his downfall as the result of crude Cold War anti-communism, Gerard and Kuklick rightly argue that Cold War tensions were more contextual, feeding into a US commitment to support Western interests and influence in post-colonial Africa; its sympathy for Nato and its Belgian secretary general; and the Eisenhower administration’s hatred of Lumumba.

Some of their other claims, however, are more problematic. Instead of seeing these bloody events as the denial of African agency, they hold that Congolese anti-Lumumba forces took independent action and had “a far better sense of their country than the intervening forces”. Second, they find evidence for an international conspiracy to eliminate Lumumba less compelling and “observe more contingency, confusion, duplication of labor and bungling”.

But both claims go against the painstaking research of Ludo de Witte, published in 2001 as The Assassination of Lumumba, which remains the most shattering and perceptive history of these events. De Witte showed just how extensive official Belgian intervention would become, immediately they realised Lumumba was neither biddable nor corruptible. They used all their means to undermine his short rule, his popularity and his image abroad. Working with sections of the Congolese elite, including Moise Tshombe, whom they helped install as leader in Katanga, and with the pliable UN secretary general, they did everything in their power to ensure that Lumumba’s Congo looked like sheer anarchy and convinced their allies in the US and the UK that everyone’s shared interest was a Lumumba “eliminated”.

They all knowingly participated in the vicious murder of a man whose final letter before he died included the words: “It is not my person that is important. What is important is the Congo, our people whose independence has been turned into a cage…I prefer to die with my head held high…rather than live in slavery and contempt for sacred principles.”

“History is unlikely to have revered him as an epic figure had he lived longer,” Gerard and Kuklick judge. I disagree.

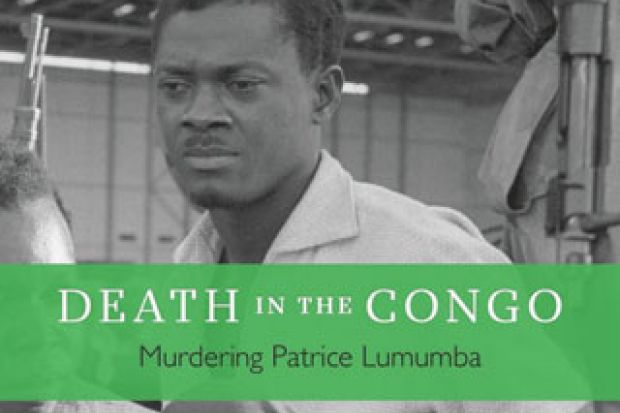

Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba

By Emmanuel Gerard and Bruce Kuklick

Harvard University Press, 296pp, £20.00

ISBN 97806747250

Published 26 February 2015