Source: Miles Cole

Download table of UK vice-chancellors’ remuneration 2012-13

Download table of average salary of full-time staff 2012-13

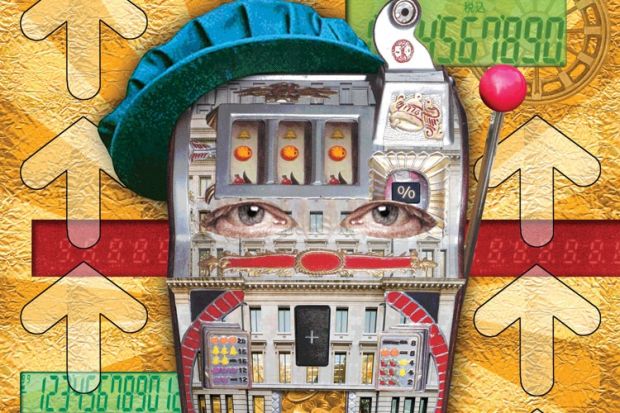

Anger about the pay rises enjoyed by so-called “academic fat cats” in charge of UK universities has been fiercer than ever this year – and the criticism has come not just from those working within higher education.

University staff who went on strike earlier this year over a “miserly” 1 per cent pay offer were, of course, the first to seize upon reports of the salary hikes received by some vice-chancellors in 2012-13.

Picket lines buzzed with talk of the “hypocrisy” of the heads who had lectured staff on the need for pay restraint amid the uncertainty of the new fee and funding system, but then pocketed increases of 10 per cent or more themselves.

Outside the higher education sector, national newspapers lapped up news that vice-chancellors from Russell Group universities had received an 8.1 per cent increase on average in the year that annual tuition fees trebled to £9,000: The Independent ran the story on its front page.

Criticism of vice-chancellors’ pay also came from politicians, most notably in this year’s annual grant letter in which Vince Cable, the business secretary, and David Willetts, the universities and science minister, said they were “very concerned about the substantial upward drift of salaries of some top management”.

The letter, sent to the Higher Education Funding Council for England in February, called for leaders in the sector to “exercise much greater restraint”.

So which recent salary rises may have caught the attention of Cable and Willetts?

Sir Keith Burnett, vice-chancellor of the University of Sheffield, is a likely candidate. He accepted a £105,000 salary increase last year, which lifted his basic pay from £265,000 to £370,000 in 2012-13.

About a quarter of this rise – £,000 – was awarded in lieu of pension payments no longer made by Sheffield after he left the Universities Superannuation Scheme, but the rest – £78,000 – was to recognise “a period of real success” at Sheffield under his leadership.

Calling Burnett “one of the most outstanding leaders in the sector”, Sheffield pro chancellor Tony Pedder said the 26 per cent overall pay rise was awarded so that his remuneration reflected “his national and international standing, and his responsibility in leading a world-class and complex organisation”.

Union leaders have questioned the rise as Sheffield has refused to pay its lowest-paid staff the living wage – £7.65 an hour – and last year the university set up a subsidiary company, Unicus, to pay wages outside the nationally agreed pay spine for higher education.

A pay rise that certainly caught politicians’ attention was the 10.9 per cent salary increase awarded to Martin Bean, vice-chancellor of The Open University, which took his overall pay and pension package to £407,000 – the third highest in the sector. Last month, MP George Galloway tabled an early day motion condemning “massive, above inflation pay rises of university vice-chancellors” and highlighting Bean’s rising remuneration package. “The appeal from universities minister David Willetts to exercise restraint has fallen on deaf ears,” the motion said.

Bean’s pay rise came despite The Open University’s student numbers falling 16 per cent in 2012-13 and its operational surplus halving to £18.8 million as part-time student levels were hit by the higher fee regime.

The Open University says that last year’s rise was awarded to restore Bean’s remuneration after he took a 10 per cent pay cut in 2010-11 as the institution adjusted to the new funding system.

The former Microsoft executive’s pay “reflects the scale and complexity” of leading a “major international organisation and the UK’s largest university with more than 200,000 students”, a spokesman adds.

But the highest-paid university head in 2012-13 was the newly arrived Craig Calhoun, whose total pay package as director of the London School of Economics stood at £466,000 in 2012-13.

The argument boils down to a growing sense of ‘us and them’: the view that a small cadre of senior managers are enjoying hefty pay rises while rank-and-file staff receive a static wage

Some £14,000 was also paid to outgoing interim director Judith Rees during a transition period, taking the overall cost of office to £480,000.

Of Calhoun’s remuneration, £88,000 was paid as a one-off sum for his relocation from the US, although his basic pay package was still almost £100,000 higher than the £285,000 paid to the LSE’s previous permanent director, Sir Howard Davies, in his last full year (2009-10).

According to an LSE spokeswoman, Calhoun’s salary was set by a selection committee tasked with finding a “highcalibre international candidate” to replace Davies, which had considered comparative university salaries when deciding “appropriate” remuneration. In 2011, 42 US college presidents were paid more than $1 million (£605,800) a year.

Overall, about one-fifth of universities increased the overall pay and pension package for their vice-chancellor by 10 per cent or more in 2012-13. And about 30 institutions increased overall emolument by between 5 and 10 per cent.

Among those enjoying a 10 per cent-plus pay rise was Steve West, vice-chancellor of the University of the West of England, whose overall pay package rose £52,434 to £314,632 thanks to a £24,158 performance-related bonus and higher pension contributions.

A UWE spokesman says that the bonus was awarded after the institution met a series of targets, including those relating to student satisfaction, financial health and graduate employability.

But were the pay rises given to vice-chancellors in 2012-13 as excessive as the headlines or ministers made out?

According to this year’s annual Times Higher Education survey of pay in the sector – the most comprehensive round-up of executive pay in higher education – overall, vice-chancellors’ salaries and benefits were 5.5 per cent higher in 2012-13 than the previous year, although this figure is affected by the fact that a number of vice-chancellors received additional salary in 2012-13 instead of pension contributions.

Excluding the Catholic priest Michael Holman, who heads Heythrop College, University of London on a salary of just £10,500 a year, and the £43,000 paid to the directors of the Conservatoire for Dance and Drama (see note to UK vice-chancellors’ remuneration 2012-2013 PDF table), average basic pay for vice-chancellors stands at £226,789.

When pension payments on behalf of vice-chancellors are included, pay averaged £254,692 in 2012-13. Overall, the total package was 3.3 per cent higher than in 2011-12.

“The increase in overall emoluments is really the key figure here,” says Ian Hartnell, head of employee benefits consultancy at the accountancy firm Grant Thornton, which compiles THE’s pay survey.

If so, then the 3.3 per cent rise is roughly the same as the 3 per cent pay increase the Universities and Colleges Employers Association says was enjoyed by non-senior staff at most universities in 2012-13. Ucea says that the figure of 3 per cent takes into account the incremental rises and merit awards received by many academics in addition to the basic 1 per cent uplift that year.

But the University and College Union takes issue with the 3 per cent figure, saying that only 42 per cent of staff receive this rise. It also cites recent data from the Office for National Statistics that found that a full-time higher education professional was paid £45,240 on average in 2013 – just £165 higher than in 2012.

In essence, much of the argument around this year’s executive pay boils down to a growing sense of “us and them” in academia: the view that a small cadre of senior managers are enjoying hefty pay rises while rank-and-file staff receive a static wage, eroded each year by inflation. The UCU claims that salaries are 13 per cent lower in real terms than in 2008.

Adding to this sense of unfairness is the situation with pensions. With the USS triennial valuation at the end of March likely to show deficits in excess of £10 billion, contributions from universities and from members may be increased and, for new members, further cuts to benefits may be required.

But about a quarter of vice-chancellors are not part of the USS; a number left the scheme last year to avoid paying punitive taxes imposed to limit high-end pension payouts – which for many vice-chancellors will exceed £100,000 a year in retirement.

Board members from big business are comfortable dealing with multimillion-pound organisations, but has their presence helped to ramp up executive pay at universities?

So what is fuelling the inflation-busting rises in vice-chancellors’ pay and pensions? The finger of blame is often pointed at “greedy” vice-chancellors, but little attention is given to those who make the decisions on executive pay: the remuneration committees.

Who sits on these boards? What performance measures are used to inform their decisions?

As part of this year’s pay survey, THE asked institutions for details about their remuneration board members, their backgrounds and the criteria used to award pay rises.

Very few institutions had any academic staff representation on their boards, which generally comprised either a council chairman or pro chancellor, a senior human resources manager and several lay members with business backgrounds, often from industries where senior academic pay would be judged to be paltry.

For example, the LSE’s remuneration committee was chaired by Peter Sutherland, the current chairman of Goldman Sachs International, which paid its chief executive Lloyd Blankfein $21 million (£12.6 million) in 2012.

Other board members include former Tote chairman Peter Jones, former Ernst & Young partner Mark Molyneux, and human resources director of Lloyd’s of London, Suzy Black, also a former Barclays director.

Although children’s charity head Virginia Beardshaw and former senior civil servant Kate Jenkins, now a visiting professor in government at the LSE, made up the board, the presence of big business was substantial.

Such people are obviously comfortable dealing with multimillion-pound organisations, but has their presence helped to ramp up executive pay at universities?

The LSE says that the committee includes “senior members of the school administration, its academic body and lay governors”, while it has “processes in place to ensure that the committee members have the relevant expertise and experience to meet the committee’s remit”.

At the University of Bath, the presence of big business is also unmistakable.

Its remuneration committee is headed by Peter Troughton, a former chief executive of Rothschild Asset Management, while other members include a former investment partner at Lazard, another global asset management firm, and a former PwC partner.

UCU branch leaders at Bath have claimed that the board’s make-up partly explains why vice-chancellor Dame Glynis Breakwell has received a series of pay rises that mean she is the sector’s sixth-highest earner, with a salary of £384,000 in 2012-13.

The branch also says that a 9.6 per cent increase has been awarded by the board to senior managers, in contrast to the 1 per cent deal offered to other staff.

Without academic representation on the board and no available minutes of meetings, the “eye-watering increases” given to senior staff are hard to fathom, says UCU branch president Marie Morley.

Morley will table a motion at this year’s UCU congress calling for universities to “publish exact details of the key performance indicators used by such committees when measuring performance…to explain the link between performance and reward”.

“The time has come for the lid to be lifted on vice-chancellors’ pay and their quite arbitrary rises fully explained,” agrees Sally Hunt, general secretary of the UCU, who says that university heads “hide behind the secretive decisions of the shadowy remuneration committees” rather than hold themselves to account.

An element of ego is also involved in the decisions. Some boards obviously feel like their university is not a serious organisation unless it’s paying its vice-chancellor £300,000 a year

When asked by THE to provide details of the criteria used to decide pay, several universities said they did not hold the data, while one – the University of Exeter – refused to state the indicators used to set Sir Steve Smith’s performance-related bonus, citing data protection issues.

“We would also like to see greater examination of who sits on remuneration committees and why,” Hunt says.

At Bath, a spokesman says that its council is “satisfied that membership of the committee should continue as currently constituted” and that its “membership is consistent with practice across the sector”, while Breakwell’s pay reflected her role as a “de facto chief executive” who had achieved certain targets.

Indeed, it does seem that many of those making executive pay decisions tend to be led by those from blue-chip companies, although charity leaders, NHS executives, headteachers and academics are sometimes involved.

Robert Gillespie, former chief executive of the investment arm of Swiss bank UBS, sits on Durham University’s remuneration board; the University of York’s board is headed by Sir Christopher O’Donnell, former chief executive of multibillion-pound medical company Smith & Nephew; and the University of Birmingham’s by former Coca-Cola Great Britain managing director Chris Banks.

The corporate nature of these boards may explain the size of the latest pay rises for senior managers, says Michael Shattock, visiting professor in higher education at the Institute of Education, University of London.

If academics set pay, they are more likely to match remuneration to existing pay levels, whereas lay governors will tend to “look outwards [and] fit it to business norms”, says Shattock, a former registrar at the University of Warwick, who believes that governors have become increasingly detached from the lives of staff and students.

“There is also an element of ego involved in the decisions,” he adds. “Some boards obviously feel like their university is not a serious organisation unless it’s paying its vice-chancellor a £300,000 a year salary.”

Jeroen Huisman, professor of higher education at Ghent University, in Belgium, who studies university governance, believes that the rising pay of vice-chancellors reflects a changed attitude among lay governors, who are moving away from their traditional role of “watchdogs”, in lieu of the state, who protect public money. In his view, governors are now more likely to see themselves as “guardian angels” who seek to import corporate methods into the running of universities.

Increased scrutiny of board decisions might start to alter behaviour, however, he suggests.

Appointments to remuneration boards are generally made by university nomination committees, which are often chaired by vice-chancellors.

Sir Nicholas Montagu, chairman of the Committee of University Chairs, which issues guidance to governing bodies, says that although remuneration committees should have at least three independent members, staff can also serve on them.

“Members of governing bodies take their responsibility for the good governance of their institution very seriously and regularly review their own effectiveness and that of their committees,” Montagu argues.

He explains that remuneration boards report to and are accountable to their governing bodies, with a variety of structures in place across the sector.

On this year’s pay rises, Universities UK, which represents vice-chancellors, says that pay “reflect[s] what it takes to attract and retain the very best leaders to UK universities in…a global market for leadership talent”.

It adds that “salaries of university leaders in the UK are in line with those in competitor countries”, such as Australia and the US. We can assume that it does not count Germany as a rival: news that some rectors in the country were earning more than €150,000 (£125,000) recently prompted public outrage.