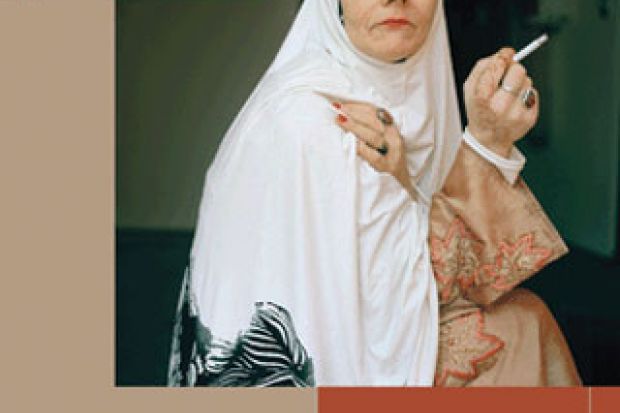

Muslims feature daily in news headlines in the West. We hear about seemingly incomprehensible ethnic tensions, long-running conflicts, hostage-takings and brutal killings. Just as difficult to understand, for many, are the growing numbers of Western converts to Islam. It is estimated that there are now about 100,000 converts in Germany, and similar numbers in France and the UK, at a time when the beliefs of Islam are seen by many as contrary to European values. These often antagonistic contradictions between ethnic, national and religious identities in contemporary Europe demand close analysis of the kind found in Esra Özyürek’s succinct study, which is supported by an extensive bibliography.

The author, a political anthropologist now based at the London School of Economics, spent three and a half years studying German converts to Islam. Of Turkish ancestry, Özyürek describes herself as a non-practising “cultural Muslim” who is able to relate to a wide variety of German Muslims. The result of her research is a fascinating exploration of the dynamics of Islam in contemporary Germany, seen through the prism of its capital, Berlin. Her account provides a multifaceted profile of the many faces of Islam in one Western European country, and it offers readers a good sense of the diversity of contemporary Sunni Muslims in Germany. But they will also be left with many questions.

How can German converts balance their love of Islam, often first awakened by an encounter with a native Muslim of Turkish, Arabic or Moroccan origin, with their compatriots’ fear of this faith? How do converts and ethnically different “native” Muslims relate to each other? What distinguishes and unites them, if anything? And why is Islamophobia so prevalent in the society that surrounds them?

The new German face of Islam reveals many unexpected characteristics. Although conversion has existed in Germany since the Weimar Republic, it occurred then mainly among upper-class Germans, while now most converts are middle and working class, and many are from former East Germany. These converts are, Özyürek argues, drawn to a pure, “culture-free”, universal version of Islam. There are, she adds, historical links with the German Enlightenment and its openness to other religions, especially Islam. The oldest German mosque dates from the late 18th century; it stood for Enlightenment tolerance towards all faiths, and it still exists.

Berlin now has more than 100 mosques and prayer houses, although only eight offer religious activities in German, while the rest cater for Muslim immigrants of particular ethnic or national groups. Some 75 per cent of Germany’s 4 million Muslims are of Turkish origin, and 40 per cent of their mosques are supported by the Turkish state, which trains and pays their imams. Özyürek contrasts the “Germanification” of Islam with the “racialization” of the Muslim immigrant community dominated by low-status Turkish workers whose integration into German society is limited. “Native” Muslims of other origins enjoy a higher status, while German converts to Islam report experiencing a dramatic loss of status among their compatriots. Although many distance themselves from immigrant Muslims, converts often become public spokespersons for Islam, owing to higher levels of formal education.

Özyürek also poses an intriguing but presently unanswerable question: is puritanical Salafism – a fundamentalist version of Islam not unlike Saudi Arabian Wahhabism that is now considered the fastest-growing Islamic movement in the world – the future of European Islam? Her study went to press before recent large-scale gatherings in Leipzig and Dresden by Pegida, a right-wing anti-Islam movement, and the counter-demonstrations that followed. The actions of Pegida have made the situation of all German Muslims, both converts and immigrants, even more complex and precarious.

Despite a paucity of statistical data, the absence of an Arabic glossary and a lack of attention to gender differences, Being German, Becoming Muslim is an excellent study.

Being German, Becoming Muslim: Race, Religion, and Conversion in the New Europe

By Esra Özyürek

Princeton University Press, 192pp, £37.95 and £16.95

ISBN 9780691162782, 2799 and 9781400852710 (e-book)

Published 10 December 2014