There is no doubt that China means business in sub-Saharan Africa. Its investment in the region rose from next to nothing in 2004 to $3.1 billion (£2.1 billion) in 2013. In the same year, according to the World Bank, China became sub-Saharan Africa’s largest export and development partner, representing about a quarter of the region’s trade.

A recent paper from Miria Pigato and Wenxia Tang, respectively practice manager and consultant in macroeconomics and fiscal management global practice at the World Bank, notes that oil and other extractive industries remain the sectors of greatest interest to Chinese investors, and there is increased interest in financial services, construction and manufacturing.

But China has also started to take its higher education partnerships with the continent more seriously. At the second summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Johannesburg in December 2015, Chinese president Xi Jinping announced “10 major plans” to boost cooperation with Africa over the following three years. These include establishing a number of regional vocational education centres and several so-called “capacity-building colleges” to address Africa’s lack of skilled workers. These will train 200,000 technicians and provide African students with “40,000 training opportunities in China”.

Xi added that China will “offer African students 2,000 education opportunities with degrees or diplomas and 30,000 government scholarships”, and invite 200 African scholars to visit China each year.

Kenneth King, professor emeritus at the University of Edinburgh and author of China’s Aid and Soft Power in Africa: The Case of Education and Training, published in 2013, says that the numbers are particularly impressive when you consider that the Chinese government has already upped its provision of scholarships for Africans to study in China from 18,000 in 2012 to 30,000 in 2015.

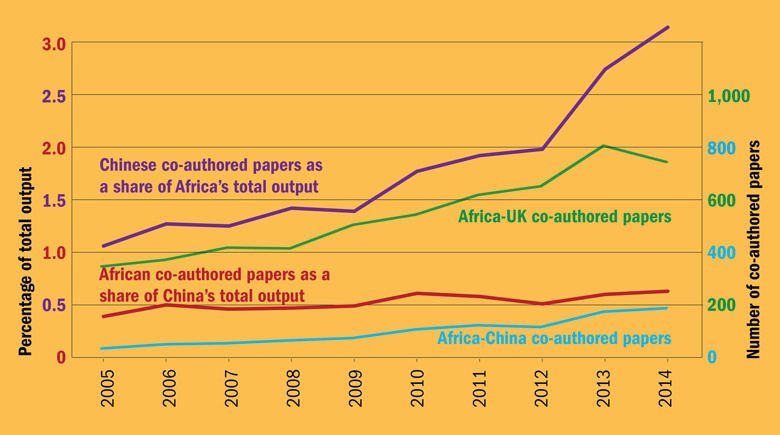

However, although the number of Chinese postgraduate students in Africa is rising, King says that student mobility between Africa and China is still primarily “one-way”. And Sino-African partnership also remains very much in its infancy when it comes to research. Figures from Elsevier’s Scopus database show, for instance, that the number of research papers in agricultural and biological sciences – a major area of concern for Africa – co-authored by academics in Africa and China has risen almost six-fold in the past decade, including a 51 per cent increase between 2012 and 2013 (see graphs). However, the numbers remain very low: the 187 co-authored papers in 2014 represented just 0.63 per cent of China’s total publication output in the field and 3.14 per cent of Africa’s, according to an Elsevier report prepared for the UK’s Department for International Development. By comparison, there were 747 co-authored papers between African and UK researchers in the same year.

Istvan Tarrosy, associate professor in African studies and director of the Africa Research Centre at Hungary’s University of Pécs, says that one reason for this low level of collaboration is African universities’ frequent inability to contribute financially to joint projects. However, he says that China’s investment in Africa is having a positive impact on research, citing China’s African Talents programme. Running from 2012 to 2015, the programme trained 30,000 Africans in various sectors and also funded research equipment and paid for Africans to undertake postdoctoral research in China.

“Last spring I visited the Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology [in Tanzania]. I saw...equipment in its laboratories that had come from China through this funding,” he says.

King also points to the 20+20 higher education collaboration between China and Africa as a key development in recent years. Launched in 2009, the initiative links 20 universities in Africa with counterparts in China.

The establishment of African centres at Chinese universities – such as the Institute of African Studies at Zhejiang Normal University and the Centre for African Studies at Peking University – has led to an increase in both the amount of Chinese research on Africa and the number of Chinese scholars working on short-term intensive research projects in the continent, Tarrosy adds. This is evident from the “series of books on higher education written in Chinese” that he has encountered at university libraries across Africa.

However, King acknowledges that while many academics in Africa and China individually collaborate on research, there is “much less” formal research between the two regions. The China-Africa Joint Research and Exchange Programme, launched in 2010, has enabled African academics to meet Chinese colleagues, but King is unsure whether this has yet facilitated much joint research.

Africa-China collaboration in agricultural and biological sciences

Source: Scoping Study: Africa-Britain-China Agricultural Technology Research Collaborations for International Development; Annex 1: Elsevier Bibliometrics Report, funded by the UK Department for International Development

In 2008, the school of public policy and management at Tsinghua University launched a one-year International Master of Public Administration scholarship programme, sponsored by the Chinese government and targeted at government officials from developing countries. It aims to share the failures and successes of China’s development with other developing nations. Meng Bo, associate dean of the school and director of international cooperation and exchange at the university, says that there are more African students in the programme than students from any other country. However, although it would like to, her department does not have many links with African institutions because most of the academics at Tsinghua “focus their research on development and public policy issues in China”. And while the rising number of African students at the institution is leading to increased academic interest in the continent, the institution needs “more funding to support joint research activities and exchanges”.

“Few faculty have worked on China-Africa relationships from economic development or international relations perspectives,” she says. “The cooperation between our school and several African universities has been established but [it is] not extensive or active enough.” However, Jinliang Li, dean of the Office of International Cooperation and Exchange at Tsinghua, adds that the institution has a memorandum of understanding with Cairo University in Egypt, reflecting the intent to collaborate. In addition, scholars at a number of African universities have visited the Asian institution during the past decade, leading to “some academic collaboration”.

Some might speculate that Africa’s universities do not have the prestige to attract Chinese partners. But King is not convinced. He says that more than half the Chinese universities in the 20+20 programme elected to join it, and many of these are highly ranked, such as Peking University (42nd in Times Higher Education’s latest World University Rankings) and Jilin University (ranked in the 601-800 bracket). That is not surprising, he says, when many of the African institutions in the scheme are also highly ranked in the region, such as Stellenbosch University (301-350) and the University of Pretoria (501-600).

King adds that China is not the only Asian nation interested in collaborating on higher education with Africa. Japanese scholars have a “tradition of doing fieldwork in Africa” while India is “seeking to follow” in China’s footsteps by creating 100 “capacity-building institutions” specialising in various sectors across Africa. In December 2015, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi also announced that the country would offer 50,000 scholarships for Africans over the next five years. And while China has “preferred to work with particular universities”, India’s approach has been to communicate directly with the African Union. King believes that this is a “positive thing” because it gives African institutions more control over how collaborations take shape, even if the process is likely to take longer.

Much has been written about China’s so-called exploitation of Africa, particularly in the Western media. Critics claim that the Asian giant is intent on extracting Africa’s natural resources and entering its markets in order to feed its own economy. For Tarrosy, China’s motives are easily gleaned: “Focusing on helping the Africans develop their own human resource capacities will help China find other sectors for investment.” However, Tarrosy argues that this is “not different from what all the other emerging economies would like to do, or even what the US would like to do”.

And while China’s approach to “soft power” has been particularly “strategic” and considered compared with other “technologically and economically advanced countries”, it is true that China “also gives a lot of things back” to Africa, Tarrosy argues. This is demonstrated by President Xi’s proposals on education, which also include a pledge to train 1,000 African media personnel.

He says that Chinese investment has improved African teaching premises and boosted human resources capacity, as well as providing research equipment.

King notes that it is “very difficult to work out the long-term impact” of China’s investment in training and curriculum development. But there is no doubting that the 46 Confucius Institutes established across 32 African countries have taught Mandarin to a significant number of young Africans, he says.

Ross Anthony, interim director of the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenbosch University, agrees that the Confucius Institutes have been China’s “major contribution” to Africa so far. He acknowledges that they are “quite controversial” in some Western countries because of the power that the Chinese government is said to exercise over their curricula and research agendas. “But here they’ve helped a lot of people to speak basic Mandarin. Universities don’t have the manpower or the resources to do that,” he says.

However, Anthony warns that African universities must think carefully about the areas in which they solicit China’s help: “When it comes to things like teaching 20th-century politics or history, it’s difficult to have Chinese involvement as they censor a lot of their own history,” he says. “In a place like South Africa, we are a very outspoken, civil society. We wouldn’t want interference in that sense.”

He adds that a university in Botswana has recently launched an undergraduate degree in Chinese and, due to lack of expertise, uses staff from its Confucius Institute to teach Chinese history and culture. “I can understand why in the short term that would be so. But certainly in the longer term you’d want to get more home-grown staff or perhaps even experts from other parts of the world,” he says.

And while there is “still a lot of scope” for Sino-African partnerships that truly benefit African higher education, he stresses that the continent should not look only to China to help it to develop world-class universities.

“A lot of [other] Asian scholars are very interested and eager to participate,” he says. “There’s no reason why Africa should solely rely on China.”

African research performance: an overview

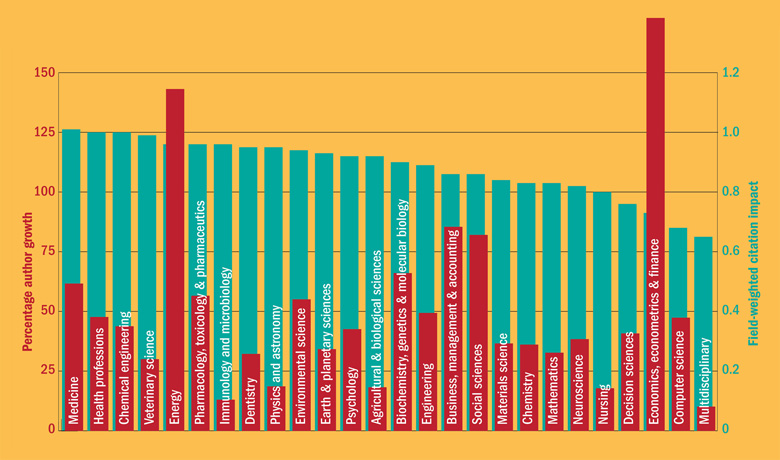

One way to assess the strength of a country or region is to look at its field-weighted citation impact: a measure of how many citations its papers receive relative to the global average. On that count, Africa’s strongest subject is medicine, in which it performs fractionally above the global average. It also performs at the world level in research related to health professions, chemical engineering and veterinary science. It is weakest in computer science, in which it performs at only 0.68 times the global average (see 'African research 2010-2014, by discipline' graph, below).

Interestingly, the fields in which African output grew most strongly between 2010 and 2014 bear little relation to performance levels. The continent’s biggest output spurt (241 per cent) was in its second weakest subject, economics, econometrics and finance. However, energy research, in which African output increased by 133 per cent, is one of its stronger subjects.

The highest-performing individual countries in some broad disciplines (see 'Top countries by field-weighted citation impact' table, below) might at first glance seem rather surprising. While the continent’s traditional research powerhouse, South Africa, is top in engineering, as judged by field-weighted citation impact, it does not figure in the top five countries for either medicine or agricultural and biological science.

The top nation for medicine is, by some distance, Mozambique, which performed at 3.82 times the global average between 2010 and 2014. In agricultural and biological science the top nation is Zimbabwe, performing at 1.35 times the global average, closely followed by Mali and Zambia.

According to Judith Kamalski, head of analytical services at Elsevier, the explanation lies in research volume. Countries with smaller outputs are more likely to have their scores skewed disproportionately upwards by a small number of very highly cited papers. For instance, Mozambique’s score in medicine is boosted considerably by two 2012 articles that garnered more than 1,000 citations and another that garnered more than 2,000, out of a total of just 111 publications. In the same year, South Africa also had four articles with more than 1,000 citations (three of them being the same as Mozambique’s), but it produced 3,987 publications in total.

“So Mozambique or Zimbabwe may really be doing well, but this does not mean we need to re-think South Africa’s position as the continent’s research powerhouse just yet,” Kamalski says.

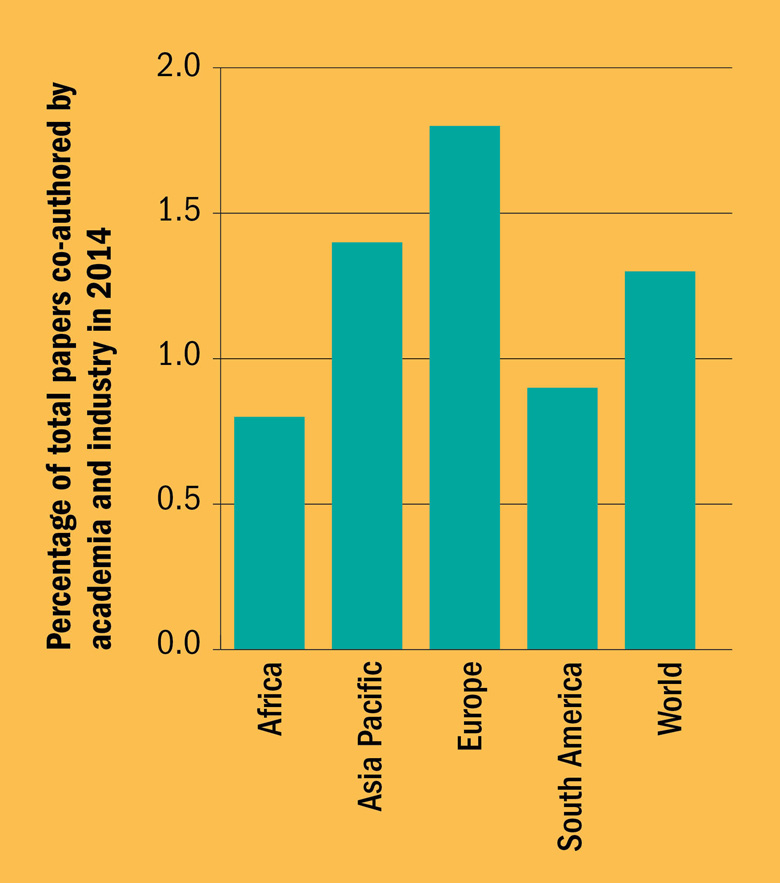

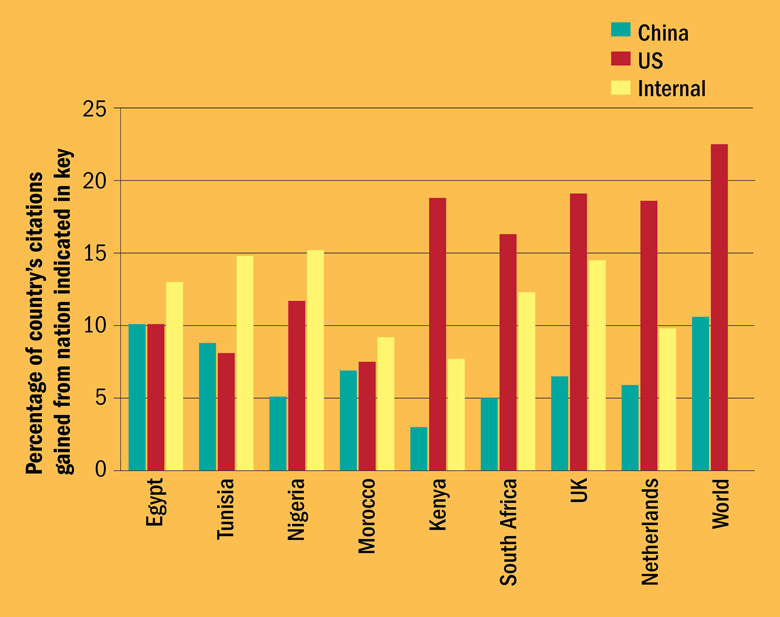

A good proportion of citations of African research comes from researchers’ own countries (see 'Who cites African research?' graph, below). Of the major African nations, this is particularly true of Nigeria and Tunisia. Compared with the world as a whole, a lower proportion of Africa’s citations come from the US or from China. Africa is also the global region with the lowest proportion of its papers co-authored with industry (see 'Levels of academic-corporate collaboration' graph, below).

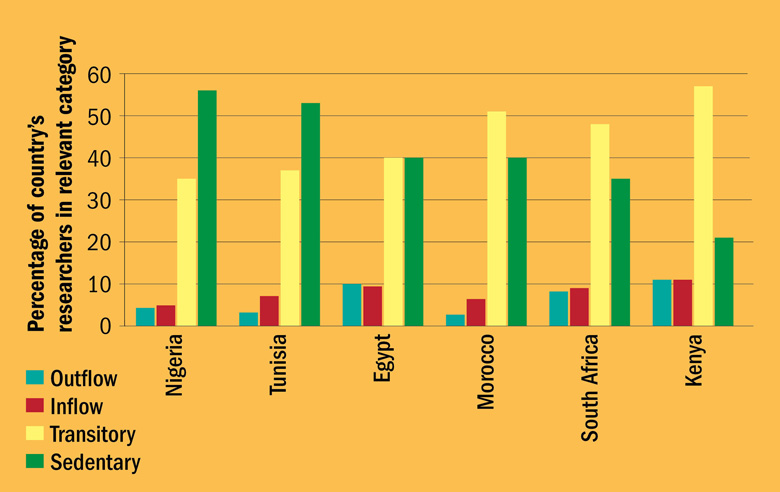

Of the major African countries, the most internationally mobile researchers are to be found in Kenya and South Africa and the least mobile in Tunisia and Nigeria (see 'Mobility of Africa’s researchers' graph, below).

African research 2010-2014, by discipline

Note: Except where otherwise stated, the source for all data is Elsevier’s SciVal tool, drawing on data in the Scopus database for the years 2010-2014.

Top countries by field-weighted citation impact

Medicine

| Country | Publications | Publications growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations | Authors | Author growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations per publication | Field-weighted citation impact |

| Mozambique | 590 | 78.5 | 13,960 | 660 | 119.9 | 23.7 | 3.82 |

| Botswana | 575 | 116 | 8,453 | 720 | 129.5 | 14.7 | 2.91 |

| Zimbabwe | 856 | 54.9 | 11,388 | 907 | 97.7 | 13.3 | 2.21 |

| Kenya | 4,454 | 51.4 | 58,269 | 4,857 | 78.7 | 13.1 | 2.16 |

| Gambia | 525 | 23.1 | 7,244 | 486 | 23.6 | 13.8 | 2.06 |

Agricultural and biological sciences

| Country | Publications | Publications growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations | Authors | Author growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations per publication | Field-weighted citation impact |

| Zimbabwe | 616 | 95.3 | 4,065 | 738 | 108.5 | 6.6 | 1.35 |

| Mali | 283 | 28.6 | 2,141 | 363 | 9.2 | 7.6 | 1.34 |

| Zambia | 316 | 33.3 | 2,383 | 423 | 59.3 | 7.5 | 1.31 |

| Kenya | 3,134 | 31.6 | 21,432 | 3,572 | 25.2 | 6.8 | 1.24 |

| Tanzania | 1,197 | 39.5 | 8,544 | 1,492 | 53.9 | 7.1 | 1.23 |

Engineering

| Country | Publications | Publications growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations | Authors | Author growth 2010 to 2014 (%) | Citations per publication | Field-weighted citation impact |

| South Africa | 7,721 | 34.8 | 28,408 | 6,767 | 37.6 | 3.7 | 1.08 |

| Egypt | 11,393 | 67.9 | 44,280 | 10,552 | 51.6 | 3.9 | 1.01 |

| Kenya | 329 | 65 | 955 | 492 | 66.2 | 2.9 | 0.98 |

| Ethiopia | 255 | 253.8 | 664 | 333 | 290.9 | 2.6 | 0.88 |

| Algeria | 7,002 | 69 | 20,725 | 8,417 | 74.3 | 3.0 | 0.87 |

Note: In these tables countries with fewer than 50 publications per year (on average in 2010-2014) have been omitted.

Levels of academic-corporate collaboration

Who cites African research?

Mobility of Africa’s researchers

Notes: “Outflow” indicates researchers whose affiliation has changed from country X to another country. “Inflow” indicates researchers whose affiliation has changed from another country to country X. “Transitory” indicates researchers whose affiliation country has changed from country X to another country and/or vice versa multiple times. “Sedentary” indicates researchers whose affiliation country did not change between 1996 and 2014. Percentages are based on “active” researchers only, defined as either those who produced at least four papers in last five years or those that produced 10 or more papers between 1996 and 2014 and at least one in the last five years.

后记

Print headline: The potential for billions