The recent bombing of a park in Lahore, which killed at least 75 people, is yet further evidence of the security challenges that Pakistan faces. And the country’s long journey to becoming a nuclear power in the late 1990s illustrates that even before 9/11, Pakistani governments have been fixated on physical and technological solutions.

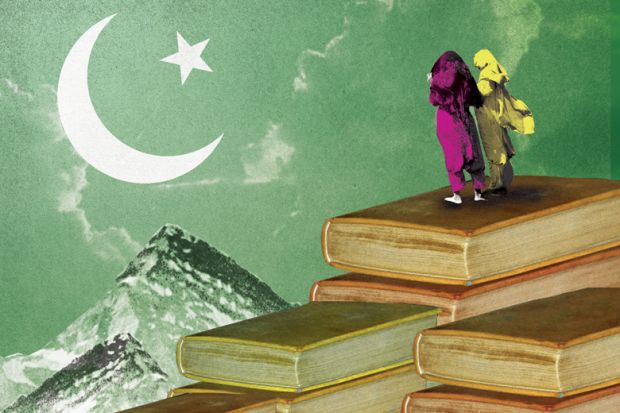

There is a strong argument that investing in what you might call human security, such as education and health, would ultimately be more effective. This is especially true given that the largest demographic group in the country is 15- to 24-year-olds, and they will have to make their way in an ever more globalised world. But equitable access to quality education has been eluding Pakistan for a long time, inhibiting its economic, political and societal development.

The country spends a little more than 2 per cent of its GDP on higher education: a low figure even by regional standards. India spends 3.1 per cent, Iran spends 4.7 per cent and even deeply impoverished Bangladesh spends 2.4 per cent. To be fair, Pakistan is trying to move towards a knowledge-based economy, and has committed to spending 4 per cent by 2018. It is also important to bear in mind that before 2000-01 there were only 59 universities in Pakistan. Following reforms that made the establishment of higher education institutions much easier, there are now 177 institutions, of which about 103 are public universities. Pakistan’s Vision 2025 programme also commits it to providing higher education to 12 per cent of its young people within a decade – only between 6 and 7 per cent are currently enrolled – and to doubling the number of doctoral students, from 7,000 to 15,000. But the figures currently appear to be rising at a snail’s pace, amid continuing concerns about quality.

Even if these goals are achieved, there is another big problem to be overcome. Universities are very unevenly distributed in Pakistan. While there are 15 public universities in Islamabad, which has a population of less than 2 million, there are only 20 in the Sindh province, where in excess of 50 million people live, and seven in Balochistan, with about 13 million people. If you were to drive the roughly 1,000 km between Sindh’s capital, Karachi, and Multan in Punjab, you would pass just three public higher education institutions.

The mushrooming of the largely unregulated private sector will further accentuate the deprivation of Pakistan’s south because, apart from Karachi, the universities are mostly being established in Punjab and people living in Balochistan and Sindh generally can’t afford the ever-increasing fees.

The lack of higher education institutions in Sindh also reflects the severe tapering of educational provision higher up the system. According to 2012 government data, there are 43,089 primary schools in Sindh, but just 2,554 middle schools, 1,639 secondary schools and 275 higher secondary schools. This reflects primary school dropout rates of nearly 50 per cent. The figure is similar for both boys and girls, but girls become increasingly more likely to drop out at higher levels of the system owing to the social, economic, cultural and political constraints they face. Less than 50 per cent of Pakistani women are literate and, of the nearly 3,000 PhDs completed by Pakistanis in 2013, fewer than 500 were awarded to women. The same year saw the first degree awarded to a woman in a Balochistan university.

Civil society organisations such as Alif Ailaan and the Rural Support Programmes Network are already working through the social mobilisation of communities to create demand and accountability for primary education. Such efforts will also be crucial in improving access to higher education, particularly in remote rural areas in general and in Balochistan and Sindh in particular – whose relative poverty and absolute deprivation affect national political stability adversely.

In addition, education has become a provincial responsibility, which it is hoped will stimulate greater efforts by local politicians to improve the situation. However, political will and leadership by the federal government will be vital. The Pakistani government’s Aghaz-e-Haqooq initiative, aimed at reducing Balochistan’s development gap, has so far awarded 600 postgraduate scholarships for Balochistan students to undertake postgraduate study, but this is just a small, belated step.

Although Pakistan’s demographic share of 15- to 24-year-olds is currently at its projected peak, the absolute size of that group is expected to continue growing. Unless young people in Pakistan are provided with access to decent education, breaking the vicious circle of economic misery and ignorance into which so many Pakistanis are locked, the country will pay a heavy price in terms of social disintegration and political disillusion and dissonance. Pakistan’s current politicians cannot allow themselves to take their eye off that ball – however loud the bang of the bombs might be.

Faisal Abbas is a member of the department of management sciences at the COMSATS Institute of Information Technology in Islamabad and is currently a visiting Fulbright Fellow at Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University. Abdur Rehman Cheema is team leader for research at the Rural Support Programmes Network, a national non-governmental organisation based in Islamabad.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Safety in numbers

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?