This is, we are told, “the forgotten history of gay liberation”. But no one I know forgot. And I’m not that old.

With his newly minted history PhD, Jim Downs attended the 2005 Tribeca Film Festival premiere of the documentary Gay Sex in the 70s, whose director Joseph Lovett was disappointed that twentysomethings were unaware of the era’s unrestrained sex. Having watched it, Downs was similarly disappointed that Lovett’s post-HIV portrayal turned the 1970s into a “morality play”. Stand by Me, his corrective to Lovett’s thesis, presents an alternative picture of 1970s gay culture as “largely forgotten”.

The book opens with a graphic tale of the 1973 Upstairs Lounge fire in New Orleans that killed 32 attendees of the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC). This introduces further stories of the religious gay community in setting the early political agenda around same-sex marriage and ministering to incarcerated gay men. Other chapters recount the lives of Craig Rodwell, founder of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in New York, and Jonathan Katz, author of the iconic study Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. Having established these religious and cultural aspects of the gay community, Downs describes the importance of, and controversial end to, the Canadian gay newspaper The Body Politic. This persuasive counterpoint to Lovett merits credit as polemic demonstrating a “good working knowledge” or “broad basic understanding”, but fails to provide new historical evidence or rigorous academic analysis of familiar events.

There is more detail on the Upstairs Lounge fire Wikipedia page, or in Downs’ own 2013 Time article, than in this book. The histories of Rodwell, Katz and Troy Perry, the MCC’s founder, are already well documented, and yet previous accounts go largely unacknowledged by Downs. Likewise, the plethora of underground newspapers in the 1970s have served as empirical data for countless stories of the radical Left, civil rights, feminist and LGBT movements – particularly The Body Politic and its controversial article on man/boy “love” that sparked outrage outside and inside the movement. But Downs claims that such elements of vibrant gay culture that “shaped the 1970s have been forgotten”. By whom?

Compounding Downs’ lack of originality is the fact that he is much less meticulously careful than most historians to avoid unfounded causal connections. Anita Bryant’s 1977 Save Our Children campaign, aimed at striking down Florida ordinances banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, was, Downs says, a reaction to the growth of gay religious groups. As an expert on the American Christian Right, I am unaware of a direct causal connection, and Stand by Me offers no evidence for this assertion.

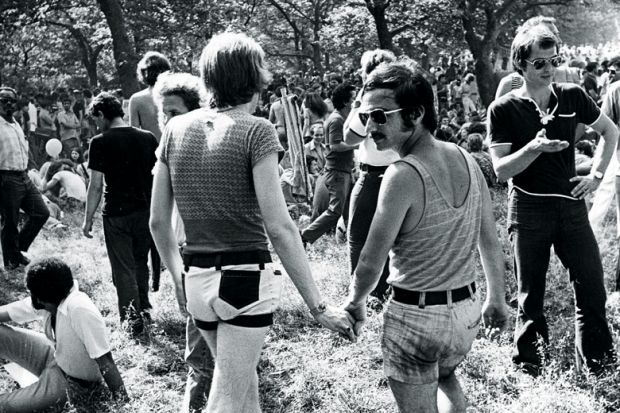

Similarly, Downs argues that the fragmentation of the “gay movement” was caused by the centrality of the hyper-masculine “clone” image popularised by the Village People. “The macho clone diminished the presence of lesbians” and “drove many lesbians out of the gay liberation movement”. Really? Most gender studies graduate students would argue that the performativity of the clone offered an ironic commentary on hetero-normative masculinity and challenged its “natural” power. The clone image is certainly not cited by most lesbian feminists or African American LGBT activists as the problem with the 1970s gay movement.

In blaming fragmentation of the 1970s gay movement on the image of the clone, Downs avoids holding white, gay, middle-class men unwilling to share power responsible. Moreover, problematising the clone becomes his excuse not to integrate lesbian, African American or other voices into his “forgotten history”. Clones were not the problem. White, gay, masculine privilege that relied on entitlement and ignored other voices was the problem.

Angelia Wilson is professor of politics, University of Manchester.

Stand by Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation

By Jim Downs

Basic Books, 272pp, £18.99

ISBN 9780465032709

Published 24 March 2016