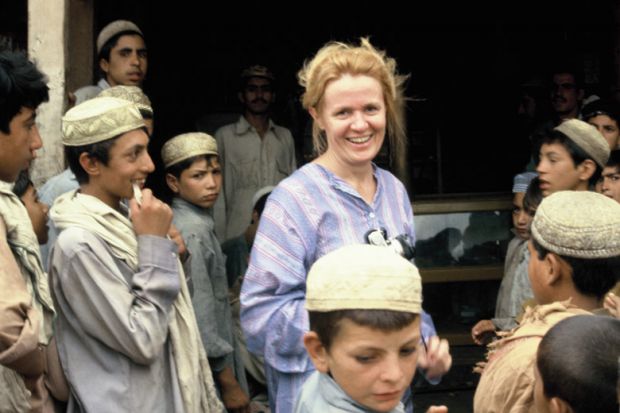

There is a lot to admire about American doctor and epidemiologist Mary Guinan. I wanted to know so much more after reading her short, episodic and frustrating memoir. Born to Irish immigrants in Brooklyn, she paid her way through the college education that her parents insisted upon for their five children (her father died when she was 15). Always the odd woman out in male-dominated classes such as chemistry (in which she excelled), she came to medicine via a stint as a flavour chemist in a chewing gum factory and then a PhD in physiology. To doubt her commitment to any of the jobs she was assigned by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), in smallpox eradication, herpes or HIV/Aids, would be a travesty.

This is a short book. It might have benefited from being longer, with more space to develop and round out the stories. Its brevity perhaps results from Guinan’s aim to bring more young people into public health medicine. She wants to engage the late twentysomethings who are pondering what to do after medical school. The woman who inhabits the first chapter, which recounts an outbreak of a dangerous bacterial infection in a military hospital’s intensive care ward, deserves her epithet “medical detective”. Yet neither here, nor in the rest of the book, is there the least hint of an egocentric display of personal brilliance. Guinan concentrates instead on the role of the senior nursing staff who in essence solve their own problem (insufficient sterilisation of some equipment in short supply). She backs this punchy whodunnit with plain talk of misogyny and the foolery of a hierarchy that will not be challenged, but this is the US military, in the 1970s. What is clear is that in the control of infectious diseases the science is, relatively speaking, the easy bit.

The need to negotiate the human side of any disease, and to do so with tenacity and compassion, is apparent throughout. The first chapter’s tight construction is subsequently lost and the stories tend to lose their shape. Although the time frames are longer and the challenges Guinan faced more amorphous, the decision of how to organise their telling seems less certain. The role of medical detective is possibly not the best vehicle, or maybe my view of it is too limited. Crime fiction is not what I read in bed. It is tricky to balance personal motivation, some background colour from the period under review, a little didactic information about epidemiology and a good story. Repetition that should have been edited out is irksome, even if it concerns an elephant in Uttar Pradesh. (They are apparently very valuable if you need to cross a deep river with no bridge.)

A story that merits its different tellings, in various chapters, is Guinan’s evolving relationship with the media and protest movements during her work on herpes and HIV/Aids. Here, she charts the changing public perceptions of these taboo subjects, bound up as they are with strong emotions and the difficulties of communicating scientific knowledge in the public arena. Her humanity is palpable, and I declare that I share her liberal non-discriminatory agenda. Those who don’t will probably find her tone strident, but I doubt that this has bothered Mary Guinan for a very long time.

Helen Bynum is honorary research associate in the department of anthropology, University College London.

Adventures of a Female Medical Detective in Pursuit of Smallpox and Aids

By Mary Guinan with Anne D. Mather

Johns Hopkins University Press, 144pp, £16.00

ISBN 9781421419992

Published 31 May 2016