I love Twitter. On logging in, I am instantly transported to a digital common room full of researchers. I get to exchange ideas, build networks and lurk in the background soaking up the conversation. Want to know what other academics are thinking about mixed methods right now? Go to Twitter, type “mixed methods” into the search bar, and within seconds you'll be scrolling through a plethora of comments and links to resources.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that I’m drawn to the “putting yourself out there” approach that Twitter embodies. In my research, I draw on lived experience and place my personal narrative at the forefront. In short, I write about myself. Using an emerging methodology called autoethnography, I engage in a deep reflective process by critiquing my multiple identities as teacher, researcher, supervisor, mentor, colleague, lawyer, administrator and leader.

Autoethnographers tell stories, but we do not want those stories to be passively consumed. Instead, we directly call on readers to feel, react, discover and care. Come into our world, we say. Come and experience what it is like, and then examine how you feel about it. This new form of ethnographic practice moves away from dispassionate description and, instead, invites response.

I am drawn to autoethnography because it gives voice to experiences that remain hidden. With that in mind, I’m delighted that higher education is becoming a popular topic for autoethnographers. Contributions include being an academic workaholic, perspectives on doctoral supervision, bullying in the workplace, career change and the university audit culture. I would, however, like to see more. In particular, experiential clinical education remains woefully under-represented

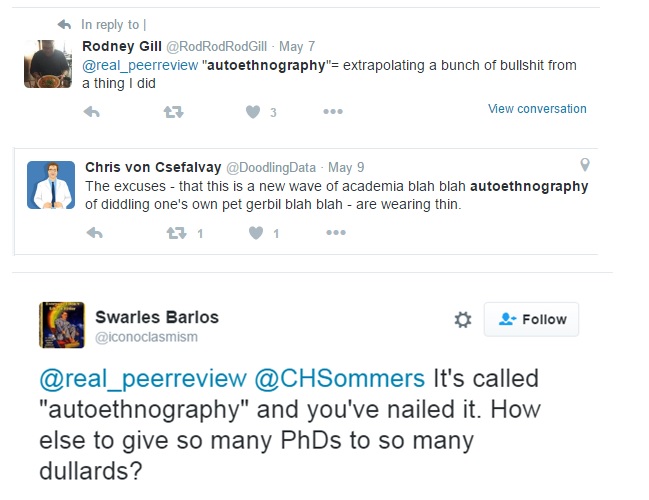

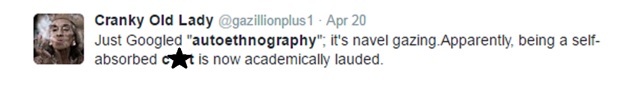

Naturally, Twitter was my first port of call when looking for other autoethnographers. I popped my head around the corner of the digital common room and asked if there was anyone else who shared my interest – or to put it another way, I typed “autoethnography” into the search bar. What happened? Well, I came face to face with a barrage of academic sniffiness. Here are some examples that I took screen shots of at the time:

According to a number of voices on Twitter, autoethnographers are “dullards” and engage in “idiocy”. One account in particular – @real_peerreview – presented itself as the protector of “real” research, trawling through journals for autoethnographic (and other unusual) works, exhibiting them to the Twittersphere alongside snide comments such as: “Yes, this person has a PhD”.

No methodology should be beyond criticism. In fact, I have an article in press that critically evaluates if and how one can ethically write about one’s life, which inevitably involves other people. I have given conference papers that invited delegates to debate the pros and cons of autoethnography. I enjoy wrestling with the academically robust critique of autoethnography put forward by researchers such as Sara Delamont. Discussion, debate, critical friends – all should be embraced. But it is not OK to shut down the conversation about emerging methodologies with comments that seek to belittle, sneer at and demean the researchers exploring them.

Academic trolling of this nature goes to the heart of what we value in higher education. Do I want my community to be associated with what, quite frankly, looks like bullying? No, and neither, I suspect, do you. We wouldn’t put up with it at a conference. We wouldn’t put up with it at an interactive seminar. We wouldn’t put up with it at a symposium. So why should we put up with it on a public forum like Twitter? Some might argue that it’s a laugh. And, to be fair, I find the tweet about "diddling one’s own pet gerbil" quite funny, but I don’t see any humour in calling someone who does research differently from you a “self-absorbed cunt”.

A few weeks back I tried to show a colleague the @real_peerreview account. But when I searched for it on Twitter, I found it had gone. I was conflicted when I discovered the account had been suspended: I wanted to assert my right not to be bullied, and to stand up for fellow researchers who were mocked. However, with the swift arrival of replacement accounts @RealPeerReview and @real_peer_rev perhaps I’ll still have that opportunity.

Ultimately, I want to encourage researchers in higher education to explore new methodological approaches without fear of ridicule. We may, of course, disagree about those methods, and we should also be able to debate them reasonably, adhering to the unspoken code of behaviour founded on respect, curiosity and fairness. But that, sadly, is not the world inhabited by academic trolls.

Elaine Campbell is senior lecturer at Northumbria Law School.

Write for us

If you are interested in blogging for us, please email chris.parr@tesglobal.com

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Twitter trolls: time for scholars to fight back?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?