What do the current editors of The Daily Mail, the i and The Sunday Telegraph all have in common? They all began their journalistic careers editing their university’s student paper. It is a well-trodden path, but it is also one undergoing rapid change.

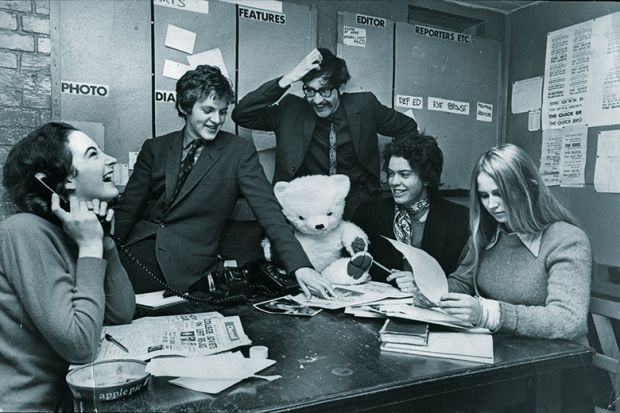

Staffed, written and produced by students, such newspapers have been an integral part of university communities for years in the UK and elsewhere.

They have often been crucial in holding university and student union executives to account. However, as with mainstream media, the internet has ushered in stiff competition for the attention of readers on campus.

Cambridge University Students Union (CUSU) recently withdrew funding for the print edition of The Cambridge Student, and The London Student, which once distributed 12,500 copies a fortnight, was forced to move entirely online in January 2015. So should student media listen to these alarm bells?

Matt McDonald, US editor of the hugely successful online student news site The Tab, believes so. He describes print student media as “basically a fun novelty”, calling it a waste of “energy unless you’ve got a particular fetish for the format or want to work in the (rapidly shrinking) print industry”.

The Tab, founded in 2009 by two University of Cambridge students, represented a major change in the world of student journalism.

Its tabloid style draws readers and writers in; the “share-ability” of its articles helps it reach an audience of millions via social media and its sometimes crude content gets people talking. Since 2009 it has expanded to 52 UK universities and, following a $3 million (£2.4 million) investment from a venture capital firm, it has also now hit the US market.

Mr McDonald said he believed the competition offered by The Tab is helping to improve standards across student media. “Our presence is what’s pushing [student papers] to become readable. We’ve just made the pre-existing market a lot more competitive,” he said.

It is naturally not a view completely shared by those working in print student media.

Ben Parr, editor of the University of Bristol’s student newspaper Epigram, said the people who make up a student paper’s target audiences “will change almost entirely every three years. This means that it is always going to be something of a struggle to be noticed by new students, and the easiest way to get noticed is for free physical print copies to be dotted around campus.”

Mr Parr argued that it is “the print newspaper which will get students to recognise who you are and, more than that, will spark their interest to write for you”.

Jem Collins, former chair of the Student Publication Association (SPA), the UK and Ireland’s biggest representative body for student media, echoed this stance in comments to The Cambridge Student when its print run was under threat. “Print media is still of paramount importance on campus, and enables engagement you can’t emulate online, and it’s important to safeguard this for future students,” she said.

Mr Parr said student newspapers also arguably provided a much better training ground for future journalists, even if each individual publication had a smaller audience than an online outlet such as The Tab.

“Anyone can get a byline on a website somewhere, but to have thousands of paper copies around your university is something I found exciting,” he said. From being held personally responsible for any libellous content published to managing the paper’s finances, in-house student media certainly offers a more rounded experience to those involved.

He continued: “If you…join The Tab, you might learn some useful things such as writing good articles and using [web publishing platforms like] WordPress, but the fact that you have a company running your publication is restricting how much you will learn. With a student newspaper you are literally just a group of students. This means you have the freedom of everything from reinventing the style of the content you publish to changing the look of your website.

“If student media turned into students just writing and uploading content onto websites owned by companies, then that would be a real loss”.

Likewise, Dan Seamarks, the current SPA chair, said that “what is absolutely not helpful is student media being run by a head office overlooking sub-brands across the country, or indeed, multiple countries. In my opinion, it depersonalises the issues and the brand from the student body, which creates an engagement gap.”

There is also the issue of the type of content that online media can skew towards.

Jennifer Sterne, editor of The Mancunion and student media coordinator within the University of Manchester’s students’ union, described The Tab’s style as “unashamedly clickbait media", although she stressed that this is “not necessarily a bad thing”.

Another way The Tab differs from traditional student media is that it is published by a for-profit company, with corporate offices in London and paid full-time staff.

Meanwhile, albeit with some exceptions, traditional student media are financially dependent on their university or student union. And while most retain their editorial independence, some have been criticised for their inability to truly hold their universities to account.

“It’s a case of fact, not opinion. Without financial independence, you’re dependent,” said Mr McDonald.

Although rare, there have been examples of universities exerting a degree of control. In 2014, Times Higher Education revealed claims that Chris Higgins, then vice-chancellor of Durham University, had put pressure on the student newspaper Palatinate not to publish articles critical of the institution. One former editor of the paper said it was as though Professor Higgins saw the publication as “an advertisement” for the university.

Ms Sterne admitted that “more needs to be done to ensure that student media can remain an independent force; I think it works in favour of both the media and student politics for this to be protected”.

But with growing competition from new forms of student media, balancing editorial independence against financial dependence may prove increasingly difficult for student journalists. The shift from a wholly not-for-profit environment to a competitive market, and the disruption brought by news being increasingly consumed online, means that traditional student newspapers’ role in the universities of the future is not necessarily set in stone.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Will The Tab kill student newspapers?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login