Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin has written a book, aimed at the general rather than specialist reader, about data and their statistical treatment, how we think about data, and how we should understand statistics. At their core, statistics attempt to reflect our understanding of the empirical world and empiricists use data and statistics to try to navigate, understand and model our natural and social worlds. Regrettably, this is a depressingly necessary book and one most appropriate to the times we find ourselves in.

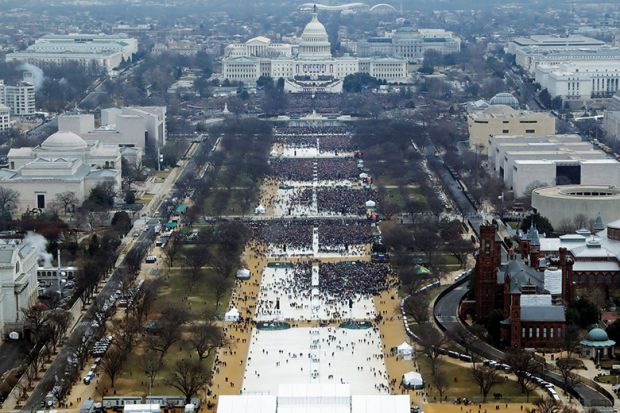

There are numerous examples of why it is so necessary and timely. Last year, in the UK, we had a former minister telling us that we have had enough of experts. I’m sure that Michael Gove doesn’t entrust his dental or ocular care to amateurs; his problem, of course, is that the experts mostly disagree with his ideological position. Last month, we had a US presidential inaugural weekend of “alternative facts”, where, as George Orwell (almost) put it in Nineteen Eighty-Four, “[press secretary Sean Spicer] told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears” regarding crowd sizes. We then had Peter Dominiczak, the political editor of The Daily Telegraph, writing that “there are currently around one million Americans working in Britain and around one million UK citizens in the United States”. Five minutes with a search engine would have led him to the Royal Statistical Society’s census estimates of 758,919 UK nationals resident in the US in 2013. Moreover, the UK Office for National Statistics estimates that there were about 197,000 US-born immigrants resident in the UK as of 2013. What’s 1 million or so missing people between friends? Of course, the issue in this and many other similar cases is the lack of provision of supporting data. The Telegraph could easily hyperlink to its data sources, but then the political spin would not be sustainable. Incidentally, the data also show that there are about 250,000 UK nationals resident in the Republic of Ireland, and about 1.2 million resident in the European Union. Spatial proximity is usually the best predictor of interaction, at the microscale of brain regions and the macroscale of political entities.

None of this would be a surprise to Levitin, who has written a book that all who are concerned with evidence and data in the public sphere should read. However, those who have adopted an a priori ideological position, and for whom data are merely instrumental, won’t read this book, because the challenge Levitin poses is to allow your assumptions to be tested by the data. And this is the core of the problem – changing your mind is unpleasant, and confirmation bias is a very powerful narcotic indeed. A Field Guide to Lies and Statistics is a useful complement to books such as Richard Nisbett’s excellent study of cognitive biases, Mindware: Tools for Smart Thinking. Levitin doesn’t venture on to the ground of the pervasiveness of cognitive biases such as “identity-protective cognition”, which leads people to systematically distort the evidence to cohere with the worldview to which they and their social group adhere. What he does do, however, is provide a necessary excursion through how to think about data, how to think about statistics, and how to do so in a systematic way. The easiest person to fool is one’s self; the best corrective to fooling one’s self is to start with things that you can measure, count and compare.

There are a few gripes. Who knows what Fahrenheit means outside the US? Placing the numerical Celsius equivalent in brackets would have been helpful. The book could also have benefited from some reorganisation. Part Three – Evaluating the World – should have been Part One (Evaluating Numbers); Part Two (Evaluating Words) should have been interleaved with Part One. The stories that we tell ourselves and the use we make of data to tell those stories are very much interwoven. It would have been somewhat more authorially challenging to do this, but it would have benefited the book’s non-specialist readers.

Levitin is not alone in his quest to have us think veridically about the world. The philosopher Harry Frankfurt gave us the wonderful essay On Bullshit (2005), where rhetoric is employed solely to convince, without regard for truth or evidence. Last month, University of Washington scientists Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West announced the wonderfully titled course Calling Bullshit in the Age of Big Data. Think of it as providing “tools for evidence-based thinking” – one that should be on syllabi everywhere. Orwell also famously wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four that “in a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act”. Fidelity to the data appears now to be similarly revolutionary; Levitin’s book is part of the necessary revolution and should be on the reading lists of the revolutionaries.

Shane O’Mara is professor of experimental brain research and Wellcome Trust senior investigator, Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin. His most recent book is Why Torture Doesn’t Work: The Neuroscience of Interrogation (2015).

A Field Guide to Lies and Statistics: A Neuroscientist on How to Make Sense of a Complex World

By Daniel Levitin

Viking, 304pp, £14.99

ISBN 9780241239995

Published 26 January 2017

后记

Print headline: Crowding out the alternative facts