Scientists, including even the greatest, often seem to live lives of two-dimensional monochrome. Not so John Burdon Sanderson Haldane. Here was an outstanding scientist whose only degree was in Classics. An Etonian, he became a Marxist and then an apostate, and at all times loved controversy. He was an immensely successful populariser of science and proselytiser for it, while strongly emphasising that scientific advance may demand difficult ethical choices. He was twice married and conducted important research on the physiological effects of deep sea diving. He had some success as a futurologist. In his final years he settled in India, finding personal fulfilment perhaps for the first time. He is well served by Krishna Dronamraju in this largely chronological biography, the first for nearly 50 years.

Haldane was born into British intellectual aristocracy in 1892 in Oxford. His father was John Scott Haldane, an eminent physiologist. His uncle was Richard Viscount Haldane, whose eponymous principle that government funding for science should be allocated by peer review has served us well for more than 100 years. Haldane was sent to Eton, which he detested and which helped him to form anti-authoritarian views. His fag-master was Julian Huxley, who became a rare lifelong friend. Haldane was a big, clumsy man who generally did not seek friendship. He loved argument. He liked to quote the classics at length and wrote reams of rather bad verse. He was refreshingly willing to consider the possibility that he might be wrong.

After a year studying mathematics at the University of Oxford, Haldane switched to Classics (Greats), yet his bent was for science. At the age of eight he was taking readings for his father’s experiments. He became interested in genetics, which had been pioneered by Gregor Mendel in the 1850s but named by William Bateson only in 1905. He served with distinction in the Black Watch regiment in the First World War, and was a fellow of New College, Oxford from 1919. He moved to the University of Cambridge in 1922, becoming reader in biochemistry. From 1927 to 1937 he also worked at the John Innes Horticultural Institution at Merton in South London. He was professor of genetics at University College London from 1933 until 1957, when he moved to the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta (now Kolkata). He died of cancer in 1964.

Haldane’s scientific reputation rests on his development with Ronald Fisher and Sewall Wright of population genetics, which established a unification of Mendelian genetics and Darwinian evolution by natural selection. Population genetics, says Dronamraju, has revolutionised human society through its application in agriculture, public health and clinical medicine. Haldane also made important contributions to chemical genetics and in 1924 he began mathematical investigations of the evolutionary process, studies that continued until his death. Dronamraju’s descriptions of Haldane’s science will be of value to biologists, even though they may be too technical for the general reader. This is a rare weakness in a book that would also have benefited from more rigorous editing – there are many repetitions – and the provision of a more comprehensive index.

In 1924, a 30-year old journalist on the Daily Express came to Cambridge aiming to interview Haldane. She was Charlotte Burghes, née Franken, and she had a young son, Ronnie. Haldane and Charlotte became lovers, but before they could marry she had to seek a divorce, a procedure that carried substantial social stigma at that time. A university committee resolved to strip Haldane of his readership, which was only restored by successful legal action. The marriage was regarded as happy for a number of years, perhaps particularly on Haldane’s side. Charlotte encouraged him to write about scientific topics for a wider public, and his writings were well received both in Britain and in the US. In 1933, Helen Spurway became Haldane’s student, and quickly expressed her intention to marry him, her senior by more than 20 years. In 1945, Haldane divorced Charlotte and married Helen. The marriage seems to have been companionable, particularly during their time in India. To his regret, Haldane never had children, and Charlotte once alleged that he was impotent.

Haldane’s most important popular work was Daedalus, or Science and the Future, published in 1923, a futuristic essay anticipating developments in reproductive biology. Its ideas for in-vitro fertilisation and human cloning were incorporated directly by Aldous Huxley in his novel Brave New World, published in 1931. Daedalus was an immediate success, and in the following years Haldane wrote articles on widely diverse topics, including the starling, social planning, Soviet genetics and how men would live in spaceships. From 1923, he also wrote a number of perceptive essays on how life may have originated on planet Earth.

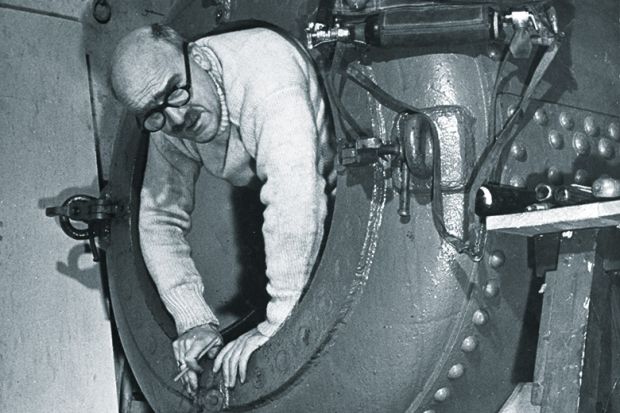

Haldane’s father did important work on safety in coal mines and also on deep sea diving and submarining. He gathered data by experimenting on himself and later on his son. Before and during the Second World War, the younger Haldane conducted further extensive experiments for the Royal Navy on the physiological effects of diving, often with himself or his second wife Helen as subject. His reaction to the extreme pain that he often experienced was to laugh, something that he did not do often.

As did many scientists at that time, Haldane moved steadily to the Left politically, influenced by his first wife, a visit to the Soviet Union in 1928, the Spanish Civil War and the rise of Fascism across Europe. The Communist newspaper the Daily Worker (now the Morning Star) supported his campaign for better air raid protection for the civilian population, and this led to a long association with the publication. Yet the 1930s and 1940s were particularly challenging times to be a communist geneticist. In the Soviet Union, Trofim Lysenko established primacy for his own perverted ideas, rigidly suppressing mainstream genetics with the support of Stalin. Haldane’s friend Nikolai Vavilov was among many purged. Haldane was for too long an apologist for Lysenko. Eventually he recognised that his first loyalty had to be science and not Marxism, and he resigned from the Communist Party in 1949.

Dronamraju was Haldane’s student and acolyte from 1957 until the latter’s death, and he has since established a successful Haldane cottage industry. This book occasionally attempts to settle old scores in Haldane’s favour, as in the discussion of Ernst Mayr and “beanbag genetics”, yet the author is well aware of his subject’s faults as well as his virtues. Dronamraju’s biography emphasises Haldane’s role as a populariser of science, yet I think that characterisation sells Haldane seriously short. He was a science educator, addressing a world of potential students. Consider Haldane on human eugenics or selective breeding, an idea then much espoused on both Left and Right. He suggested that far too little was known of genetics for its practical application to be wise. He pointed out that arriving at any worthwhile result would take a very long time. With typical originality, he suggested that any eugenics programme should have peace as a central aim, since war inevitably leads to the destruction of the fittest on both sides. The eminent physicist Freeman Dyson has claimed that Einstein and Haldane were the first two scientists to place a firm emphasis on the importance of ethical issues in relation to scientific advance. Their like must be prized above rubies.

Richard Joyner is emeritus professor of chemistry, Nottingham Trent University.

Popularizing Science: The Life and Work of JBS Haldane

By Krishna Dronamraju

Oxford University Press, 384pp, £22.99

ISBN 9780199333929

Published 23 February 2017

The author

Krishna Dronamraju, president of the Foundation for Genetic Research in Houston, Texas, was born in Pithapuram in India. “My father died of typhoid fever when I was five years old. I was brought up by my mother with much care and love. She inspired me by drawing my attention to my father’s scholastic records, which she had carefully saved; especially his outstanding performance in math and science. Although she did not receive a higher education, my mother was intelligent and emphasised the value of education in our lives. She often mentioned our scholastic tradition and the Brahmanical values and pride of scholarship which have been passed on for many generations in India.”

Following undergraduate study at Andhra University, Dronamraju “went to Agra University because it was one of the few universities at that time where one could obtain a master’s degree in genetics. It was a remarkable coincidence that I had just received my MSc in 1957 when I learned from a local newspaper that the famous scientist J. B. S. Haldane and his wife had moved to India to work at the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta.

“I wrote to him to enquire if I could study with him. He replied at once and proceeded to test my knowledge of genetics, in writing as well as in person. The rest is history!”

Dronamraju recalls a mentor who was “much more tolerant and agreeable in our daily contacts than the picture often portrayed in the popular press of a difficult and irascible personality”.

What sort of advice did Haldane give his protégé? “I learned much from his policy of not reaching conclusions unless all possibilities were taken into consideration. He was the most open-minded scientist I have come across in my entire career. So many people in science tend to be extremely dogmatic, clinging to their own little theories...Haldane’s world was much bigger than that of his colleagues and many others.

“To my great surprise, he welcomed my criticisms of his research papers and ideas. I was a young student, but Haldane treated me with much respect and consideration, almost like an equal colleague, which was unheard of in those days or even now.”

What gives Dronamraju hope?

“New generations give me hope! Younger scientists are constantly appearing in science and may find a new way of doing science with more freedom as in the past, not limited by Nobel prizes, academy honours and other trappings of modern society. Also, new ideas arise when science and the arts interact more. My colleague, Michele Wambaugh, has just written an excellent play called JBS (based on my book) which is awaiting publication and production by some enterprising individuals!”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: Fantastic feats and how to describe them