To those outside the country, the French higher education system can be rather baffling. A unique mix of elite, specialist and often opaquely named grandes écoles, much larger, non-selective universities and a complex system of research institutes, it lacks the kind of generalist powerhouses in teaching and research that achieve prominence in global rankings and draw top student and academic talent from around the world. It has only one institution – École Normale Supérieure – in the top 100 of Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings, and just four in the top 200.

Despite a general national faith in the French way of doing things, concerns about international visibility and comparability have prompted a sequence of higher education reforms over the past decade. One trend is towards greater autonomy for universities. In 2007, Valérie Pécresse, minister for higher education and research under centre-Right president Nicolas Sarkozy, introduced the so-called LRU law – Liberté et Responsibilité des Universités. This was designed to move French institutions closer to the Anglo-Saxon model, with more freedom to spend their budgets and create partnerships with the private sector. Sarkozy himself declared 2009 a “year of action and reform for higher education, research and innovation”. Noting that all of the world’s great universities were autonomous, he said greater autonomy would free French institutions from “an infantilising system, paralysing creativity and innovation”. And he further offended the sector by suggesting that the French researchers who had won Nobel prizes and similar honours were merely “the tree which hides the forest”, used as an “alibi” by “conservatives of every [political] complexion”.

Despite such provocations – and the fact that Pécresse’s plans to reform teaching training and the status of lecturers attracted widespread public protest and led to strike action by academics – the LRU law set a direction of travel that continued even after Sarkozy was succeeded by the socialist François Hollande in 2012.

Search for university jobs in France

The other major trend in reform relates to the consolidation of institutions. The 2013 Law on Higher Education and Research led to the creation of a number of new groupings known as ComUEs (communautés d’universités et établissements), which bring together universities, grandes écoles and research laboratories into administrative units that have the potential to pack a much greater punch than any of the constituent units could individually.

One prominent example is Paris Sciences et Lettres – PSL Research University Paris – which includes 18 Paris institutions, among them École Normale Supérieure – as well as three national research organisations. According to its president, Thierry Coulhon, its legal status “is going to evolve soon, as the member institutions have recently concluded a political agreement in order to go further together”. For instance, “this year we will submit to [the THE rankings] as a single institution, and we will do the same with [the Academic Ranking of World Universities, also known as the Shanghai ranking] as soon as they [agree] to consider us”.

The closer integration of the PSL institutions will also increase Coulhon’s powers, “mainly over the budget and the strategy” of the conglomerate, he says.

For all its struggles to come to terms with the international model of higher education promoted by rankings, the French system remains far from insular.

According to a recent paper by Johannes Angermuller, professor of discourse at the University of Warwick, top professors in France – who are usually civil servants – are paid far less than their peers in other Western countries, since state bureaucracy prevents them from negotiating higher salaries. That may partly explain the high numbers of French academics based abroad; according to a recent study, only 43 per cent of French academics return to France within three years of completing a PhD in a different country.

But the upside of the French system, according to Angermuller’s paper, “Academic careers and the valuation of academics. A discursive perspective on status categories and academic salaries in France as compared to the U.S., Germany and Great Britain”, published in the journal Higher Education, is that academics enjoy “almost total job security”, as well as “democratic inclusion in decision-making and job autonomy”. And the country certainly appears to have an attraction for foreign academics. Of the 43 France-based researchers who won mid-career consolidator awards from the European Research Council in 2016, for instance, only 28 were French nationals: a lower proportion of nationals than for Germany or Spain, for instance.

As for students, a report published in February by Campus France – the agency responsible for international recruitment – indicates that the country attracted 310,000 foreign students in 2015: just over 7 per cent of the global total and more than any other country except for the US, the UK and Australia.

Moreover, with the votes for Donald Trump and Brexit making the first two of those nations potentially less attractive to many international students and scholars, France is well placed to further boost its share of the market. Campus France’s director, Béatrice Khaiat, has recently been to India and has had meetings with the ambassadors of Mexico, Iran and Afghanistan. All are countries looking to “reorientate” their plans for international students in light of the rise of populism in the US and UK, she says.

But, of course, France has its own populist icon in the form of Front National leader Marine Le Pen, who is expected by pundits to win the first round of this Sunday’s presidential election. The far-Right leader constantly savages immigrants, Muslims and the European Union. And although she is thought highly unlikely to win the second, run-off election between the top two candidates on 7 May, her rhetoric could still do considerable damage to the international attractiveness of French higher education.

In his “address to a future President of the Republic ” in February, Gilles Roussel, president of France’s Conference of University Presidents (CPU), makes no comment on particular candidates. Nonetheless, his stress on the need for universities to avoid “any discrimination based on origin, religion or opinion” could be seen as aimed at Le Pen – as could his references to universities’ role in “strengthen[ing] European citizenship” and the importance of European research partnerships under the aegis of the EU.

Jean-Michel Blanquer, director of ESSEC Business School, a grand école with two French campuses as well as one in Morocco and one in Singapore, believes a Front National victory would certainly taint “the image of France” and represent a psychological blow to Le Pen’s many opponents in academia. It could also put European funding and research programmes at risk if she followed through on her anti-EU rhetoric, he says. As the head of “a very international institution in continental Europe”, Blanquer has already witnessed increased interest from “people previously going to the UK and US”. A similar context in France could easily have similar consequences, he fears.

In her 144 Engagements Présidentiels (144 presidential pledges), aimed at “putting France back on track”, Le Pen has relatively little to say about higher education. But she certainly appears to have no truck with French institutions’ increasing efforts to boost internationalisation by teaching in English. She intends to “defend the French language” by repealing a law that allows universities to “limit the amount of teaching they do in French”.

Frank Bournois is dean of the pan-European ESCP Europe business school, where students are not allowed to spend more than two semesters on a single campus. It would be “problematic” for an institution such as his if a Le Pen administration decided, for example, that “it would not have recognition if it taught less than 80 per cent of its programmes in French”, he says.

Le Pen is also keen to “defend the French model of higher education, which depends on the balance between universities and grandes écoles ”. While students enter university directly after the baccalaureate at the end of secondary school, the grandes écoles generally require an additional two years in specialist classes préparatoires. Their alumni dominate the leading positions in French society – the country’s last four presidents all attended the Paris Institute of Political Studies, generally known as Sciences Po (although Sarkozy didn’t graduate). This has led to much debate about their elitism, the need to widen access and to make their graduates more aware of “the real world”. But while Le Pen is elsewhere scathing about elites, Valérie Gauthier, an associate professor at HEC Paris business school, argues that “the French elite system [in higher education] suits her because it promotes the idea of France as a strong nation”.

Gauthier also points out that if Le Pen “wants an education that is more francophone”, that will mean either reducing international student numbers, or recruiting an even greater proportion of them from francophone North Africa – whose largely Muslim residents she is particularly keen to keep out. (She has accused her presidential rival, the centrist Emmanuel Macron, of wanting to create a “migrant motorway” between the Maghreb and France.)

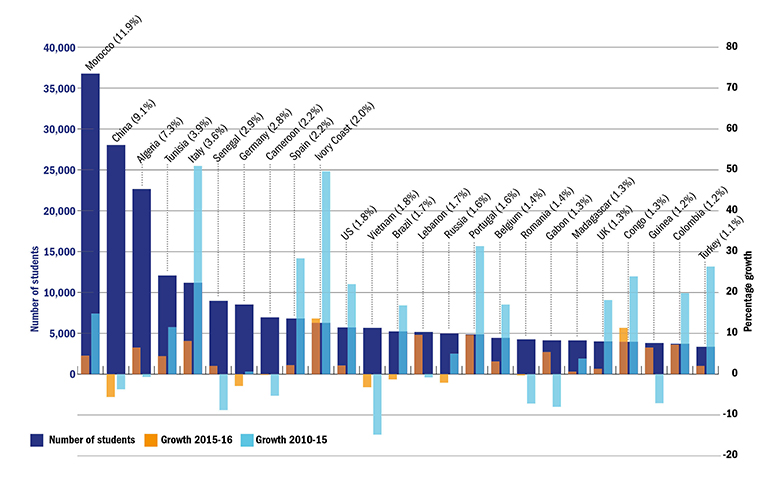

In 2015-16, for example, according to figures from the Campus France report, France attracted about 37,000 students from Morocco, 23,000 from Algeria and 12,000 from Tunisia, as well as 28,000 from China (see graph). This represented more than 62 per cent of internationally mobile North African students, but only a tiny proportion of their Chinese peers.

France also dominates student recruitment from sub-Saharan Africa, attracting 15.7 per cent of the total, ahead of South Africa (12.3 per cent), the UK (11.4 per cent) and the US (10.9 per cent). The split is largely on linguistic lines. While France attracted 71.2 per cent of francophone Madagascar’s 4,218 internationally mobile students in 2014, for example, it has made virtually no inroads into the vast market in anglophone Nigeria.

This reflects the fact that just over three-quarters of internationally mobile anglophone students opt to study in anglophone countries, a preference largely shared by Chinese and South Korean international students. Only 4.4 per cent of North American and a tiny 2.6 per cent of Asian students chose France as their destination in 2015-16. Nevertheless, Campus France’s Khaiat argues in the February report that France’s international students offer “multiple, strategic and lasting” benefits to the country. Noting that four out of 10 doctoral students in France are not French, she says international students bring “international knowledge essential for research and innovation”.

To enhance the soft power benefits of international students, Campus France launched its France Alumni network in 2014 to “unite, inform and guide foreign students who studied in French higher education”. Representatives in more than 60 countries organise social and networking events, cinema weeks and receptions at French embassies on Bastille Day. A directory of all members allows alumni to keep in touch, and partner organisations such as businesses can access non-sensitive data about potential employees.

France’s international student recruitment

Source: Campus France’s Étudiants Internationaux report

Tawfik Jelassi, professor of strategy and technology management at the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne, Switzerland, served in 2014-15 as interim minister of higher education, scientific research and information and communication technologies in Tunisia during its transition to full democracy. Prior to that, he was dean of the School of International Management at France’s École des Ponts ParisTech.

He confirms that “people in Tunisia who want to continue their studies abroad first think of France”. And a victory for Le Pen would “have a psychological effect on the people on the other side of the Mediterranean”, and perhaps lead them to “think of other French-speaking countries, such as Belgium, Switzerland and Canada” instead. A Front National victory could make it “much more difficult for foreign students, especially from Maghreb countries, to get visas”, especially long-term visas. The impact would be particularly acute for doctoral students who wanted to come to France with their families, he predicts.

So what of the other presidential candidates? François Fillon, the centre-Right candidate, was prime minister under Sarkozy at the time the LRU law was introduced, so it is unsurprising that he proposes to continue in the same direction. However, his candidacy appears to have been dealt a fatal blow by a scandal about payments to his wife for allegedly minimal or non-existent work, leaving Macron as Le Pen’s main rival.

Macron is also in favour of the current trajectory. In his election manifesto, he pledges to “liberate the energy of our universities by giving them real and concrete autonomy” in terms of curricula and recruitment of staff, so they can “adapt to the diverse needs of students”. Evaluation procedures will be simplified and sources of funding diversified. At the same time, Macron will “support the formation of world-class universities on the basis of voluntary groupings of universities and grandes écoles with the support of research institutions”.

Furthermore, in order to make France “a global leader in research on global warming and environmental transition”, Macron’s administration would speed up the provision of visas to “foreign specialists in these fields”, as part of “a general policy of openness to all researchers and talents”. He has posted a YouTube message in English urging “American researchers, entrepreneurs and engineers working on climate change” to come to a country whose head of state has “no doubt about climate change”.

“We think we are halfway in terms of autonomy,” says PSL’s Coulhon, who is also an adviser to the Macron campaign. “But there is a difference between what is in the regulations and what really takes place.” One example is student evaluation of courses, which is supposed to be carried out every semester – albeit only for universities’ internal use, with no funding riding on it. “It doesn’t happen!” Coulhon says. “Macron would want to push that forward.”

The overall aim is “a system that is regulated but diverse, to reach the goal of social inclusion”. Macron believes in “acceptable differentiation”, Coulhon says. “Not every university has the same mission, strengths and characteristics. It sounds obvious, but in France, [although] nothing is uniform, we pretend it is. That makes life difficult in terms of international competition and so on. We have to support different kinds of excellence. We need a new contract between the state and the institutions rather than a priori regulation. It should not be one size fits all.”

Coulhon adds that universities should publish statistics such as dropout rates, graduate employment figures and course-specific graduate salary data “so students make a choice with proper information – and funding should also follow results in research and innovation”.

Physics professor Bruno Andreotti takes a far more jaundiced view of the French higher education system’s efforts to pursue “‘simplification’ and ‘international visibility’”. His own situation, he explains, reflects the “lasagne plate model” that has been created: “piles of structures embedded one inside the other, each inducing a lot of bureaucracy”.

He does his research at École Normale Supérieure but his salary is paid by Université Paris 7 – Paris Diderot, where he teaches. The latter is part of the Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (USPC), another ComUE created during the past five years.

Andreotti dismisses both PSL and USPC as “totally useless”. As well as being arbitrary groupings that have so far failed in their declared objectives, he believes they have “absorbed in bureaucracy a lot of resources: most of the thousand positions promised by Hollande were [administrative]. Feudalism and cronyism have increased a lot in these structures, which can be described as Potemkin villages: fake universities that have nothing to do with actual research and teaching.”

This is all part of what Andreotti sees as the gradual “mutation” of universities, in the name of “excellence” and “autonomy”, into something resembling companies. “The system is now in a critical state…Most probably, with Macron or Fillon, it will finally be transformed into a system similar to the US system. But the history is so different that chances are high it will actually produce a disaster,” he says.

Some of Andreotti’s policy ideas have been adopted by the left-wing presidential candidate Jean-Luc Melénchon, who is currently fourth in the polls ahead of socialist rival Benoït Hamon. Melénchon’s electoral programme argues that “the consequences of marketisation” in the public sector are “furthest advanced in higher education” – including “competition between establishments”, “inadequate and unpredictable funding” and the “precarity” of students and early career researchers. He therefore proposes to repeal the LRU law and its successors, dissolve the ComUEs and put a stop to what he calls the “feudalism of university presidents” in the interests of a “democratic and collegial” system of management. If he becomes president, he would increase university budgets and supply constant rather than project-based funding for research. He would also challenge the traditional division between universities and grandes écoles.

Melénchon would also end the “permanent, time-wasting and bureaucratic” evaluation of universities. Andreotti interprets this as a reference to newly introduced “micro-funding agencies for almost everything” and the need for universities to apply for different kinds of status, such as “macro-universities” and “macro-laboratories”.

“As I understand it, the statement refers to the ideology of neoliberalism: creating market everywhere through competitive calls,” Andreotti says. “Juries then produce evaluations based on their assessment of the quality of management and not at all based on facts regarding the production of research and the quality of teaching.”

Andreotti also references the bureaucracy around promotion and the recent “unfreezing” of Sarkozy’s original intention – shelved after the strikes mentioned above – to introduce assessment of individual academics, which he fears may lead to the assigning of more teaching duties to those deemed to be underperforming in research.

Many working in the sector feel that, despite displaying such different approaches to higher education, the presidential candidates have shied away from some of the essential issues.

ESCP Europe’s Bournois regrets the lack of “stronger messages about Europe and the international dimension, and how Europe can become stronger through higher education”. And HEC Paris’ Gauthier – who has produced a Coursera programme on inspirational leadership that has been taken by nearly 60,000 people – is disappointed that, even when candidates such as Macron and Hamon touch on “digital transformation”, they fail to “relate it to education [even] though it is the source of evolution and even revolution in HE. It is there you break the barriers and frontiers.”

And ESSEC Business School’s Blanquer laments the gap between the public funding available per student and what is really needed. The gap should be filled by the state, “but the state cannot afford it, so we need to invent new ways to finance it”. This will probably require “some innovation in the future, in terms of [student] loans”. But he is yet to hear anything “very precise” about that possibility from the presidential candidates.

According to higher education consultant Sebastian Stride of SIRIS Academic, French politicians have been wary of addressing questions of loans for fear of provoking protests from voters. They have also shied away from confronting the lack of selectivity among university entrants, which means that any student who has passed the secondary school baccalaureate has “the right to follow any university course whatever their prior field of specialisation”. The fact that those with a baccalaureate in humanities can enrol on a medical degree inevitably leads to high dropout rates, he says.

But he sees at least cautious signs from both Fillon and Macron that they are willing to confront these challenges.

“That is why this election is so important,” suggests Stride. “If you’ve got a government which increases the autonomy of universities, which tackles taboos such as selection and differentiation of higher education and research, and which sends a strong message saying ‘We’re open, come here’, France has enormous potential.”

后记

Print headline: Liberty, autonomy or permanent bureaucracy?