The measures on higher education set out in Australia’s 2017-18 federal budget are, of course, promoted as being student-centred and all about accountability, sustainability and transparency. However, the underlying agenda is much more palpably about securing savings in public outlays and constraining the runaway growth in student loan costs, which have been fuelled by an expansion of student numbers in both the university and vocational sectors.

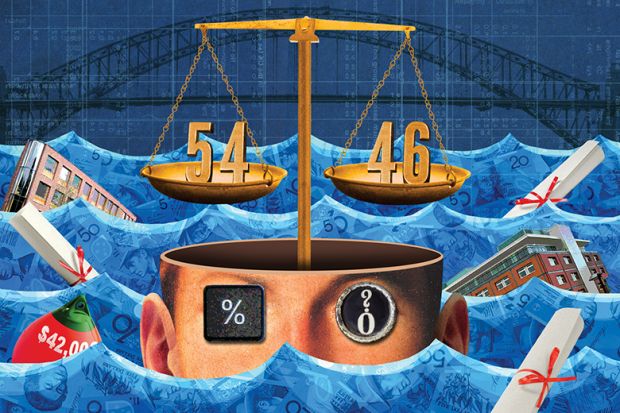

The headline element of the higher education budget is the phased-in rebalancing of the mix of government and student contributions to tuition costs, from an overall 58:42 split in 2017 to 54:46 by 2021. This will involve an increase in tuition fees for students commencing in 2018 of 1.8 per cent, climbing to an accumulated 7.5 per cent rise by 2021.

In addition, a lower threshold and a new sliding scale of repayment levels will be applied to all holders of student debt, with the threshold for commencing repayment lowered from the median earning level of nearly A$56,000 (£32,000) in 2017 to A$42,000 from July 2018.

The likely passage of these measures will end the policy hiatus that Australian higher education has suffered over the past three years. In 2014, the incoming conservative (Liberal-National) government announced that it was looking for savings but at the same time sought to make radical change, proposing the deregulation of university fees and abolishing distinctions between public and private institutions. But these plans failed to win the support of the Senate, despite being resubmitted in 2015.

By 2016, deregulation had been dropped, although a 20 per cent cut to government grants remained on the books. A discussion paper was issued on possible alternatives, but the search for a middle path between the status quo and deregulation did not yield fruit. And here we are now, in 2017, faced with measures that, in character, are similar to those proposed in 2014 but lighter in touch.

In the 2016/17 financial year, the Australian government outlaid some A$9.4 billion for subsidised university places, including A$2.4 billion in student loan subsidies: a figure that will increase significantly over coming years. Of course, expenditure on schools, health services and national disability insurance will also continue to grow, and successive governments have sought to offset that growth. Universities have been one target for savings, and the latest budget measures are expected to save A$2.8 billion over the next four years.

While students will pay more, universities will receive less. An efficiency dividend is to be applied (an Australian budgetary euphemism for a small, arbitrary cut to annual grants): in this case, 5 per cent over two years. It is a classic Catch-22: the message is that universities must be prudently managed, but if they are and they have generated surpluses, governments will feel free to use the presence of these surpluses as a rationale for trimming budgets. This is hardly an encouraging prospect for the sector, but it does explain the support given to the 2014 reforms by vice-chancellors, who saw it as the last chance to escape the tender mercies of government patronage. In addition, under the new proposals, 7.5 per cent of the government grant will be put at risk – that is, allocated on the basis of performance against measures yet to be decided.

Sector leaders can hardly be expected to be advocates for cuts to their budgets, but pressures on public finances and demands for accountability are facts of life that were entirely expected once deregulation was politically dead. We might all hope for enlightened governance that will ensure sufficient funding for universities to be able to fulfil their vital missions to the extent that people expect. But many view universities as undisciplined and wasteful, spending too much on administration or indulgences. Universities can expect to receive little sympathy for their situation.

Similarly, we should not be surprised that performance-based funding for university education has arisen again, despite past failures, and it is likely to gain support from outside the sector. As with England’s teaching excellence framework, the policy has been announced without detail as to how it might work, and, initially, simple compliance with administrative reforms is all that will be involved. The acid test will come later, as the methodology for allocation is settled. It might appear that, as Talleyrand said of the restored Bourbon dynasty, ministers have learned nothing and forgotten nothing. Perhaps, this time, we will not see universities expected to deliver incremental annual improvements in areas that are driven mainly by external factors such as economic change and complex student circumstances. Perhaps the scheme will not penalise institutions that recruit older, off-campus or part-time students or that do not draw from the top ranks of school achievers. With some goodwill and commitment from both sides, perhaps this time it will indeed be different.

There has been remarkably little blowback over proposed changes to student loan conditions that are retrospective in that they will affect all current holders of student debt (graduates and students alike) as well as future cohorts. Some Senate cross-benchers have called for even lower repayment thresholds, recasting loans as debt that must be repaid regardless of whether graduates secure the expected earnings advantage of higher education. No doubt policymakers in England will make note.

There are no easy answers to funding higher education, and, with seemingly inevitable cost increases, either students or governments will have to pay more. For their part, universities cannot expect to avoid making hard decisions to find more efficient and perhaps radically different ways of doing their business and providing high-quality services. The budget measures are by no means a resolution of this quandary, particularly with the issue of funding for research infrastructure remaining unresolved. Yet the new proposals are less disruptive than some of those that had been aired. With that modest consolation, universities can continue their work and look to the future to find clear and coherent foundations to sustain Australian higher education and research.

Peter Coaldrake is vice-chancellor of Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

后记

Print headline: A delicate balancing act