Nearly half of English vice-chancellors surveyed by Times Higher Education believe that the country's tuition fee system is unsustainable, with a third of those questioned backing Labour’s policy to abolish fees, suggesting widespread desire for major reform at the sector’s highest levels.

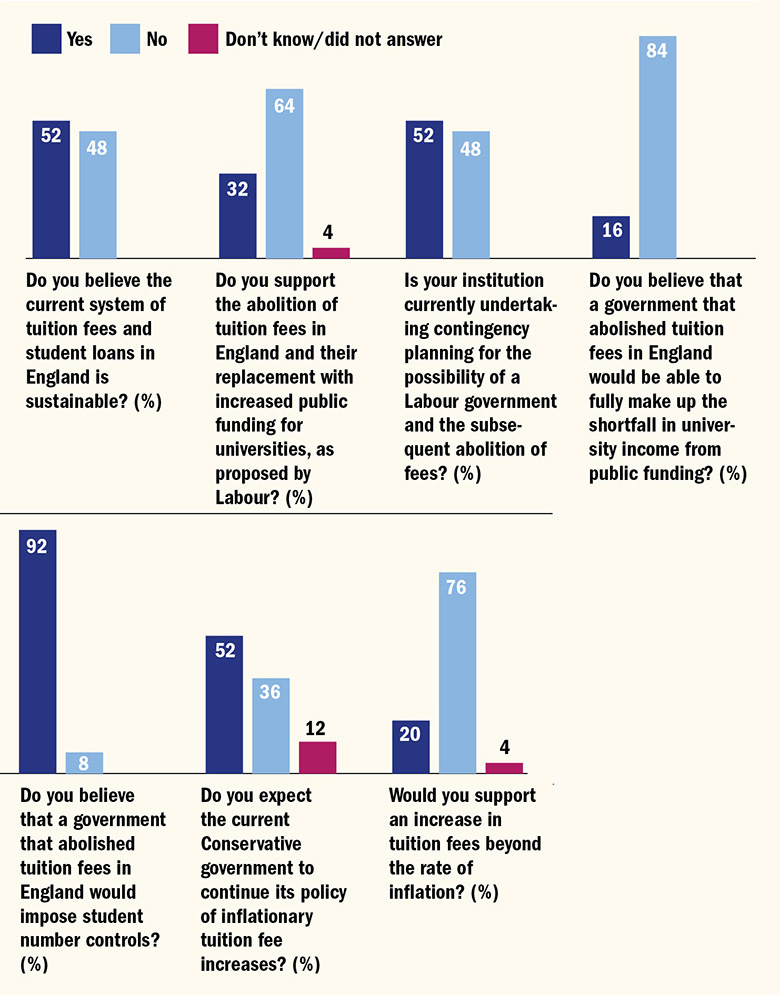

The survey also showed that many vice-chancellors doubt whether the government will go ahead with plans to raise fees in line with inflation for institutions participating in the teaching excellence framework, beyond the rise to £9,250 already in place for this autumn. Not raising fees in line with inflation would deal a major blow to universities' finances. Asked whether, given the current debate on student finance, they believed that the government would go ahead with inflationary fee rises, just over half (52 per cent) said yes, while 36 per cent said no and 12 per cent said that they were unsure.

The current fee system is now under intense political pressure following the perceived success of Labour’s policy in the general election and a damning report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies highlighting the regressive nature of changes, made after the trebling of fees, to abolish maintenance grants and freeze the loan repayment threshold at £21,000.

The Conservative government will not be able to rely on the sector for a unified defence of the status quo, suggests the THE survey of vice-chancellors, which gained 25 responses – about a quarter of all English universities.

Asked whether they believed that the current system of tuition fees and student loans in England is sustainable, 52 per cent of university leaders said yes and 48 per cent said no.

On the question of whether they supported the abolition of tuition fees in England and their replacement with increased public funding for universities, as proposed by Labour, 32 per cent said yes and 64 per cent said no.

Vice-chancellors appear to regard the election of a Labour government and the abolition of fees as a real possibility, with a slim majority (52 per cent) saying that their institution was undertaking contingency planning for this scenario.

Desire for reform: vice-chancellors responses to survey questions about tuition fees

Source: THE survey of 25 English vice-chancellors

David Green, vice-chancellor of the University of Worcester and one of those who backed Labour’s policy, said that the current system of tuition fees was “politically unsustainable”.

“There is a tsunami of opinion that the current system is plain unfair – with too much debt and too high a rate of interest.”

Professor Green, an economist, added that, under the current system, “institutional instability on a wide scale is just two or three years away” given demographic change, threats to European Union and international student recruitment and intense competition between institutions. “Fundamental reform is needed now,” he added.

Sir Keith Burnett, vice-chancellor of the University of Sheffield, told THE separately from the survey that reform was urgently needed.

“If we let it carry on I think that it will result in a decreasing political consensus for the present system,” he said. “You can see it rotting quickly.”

However, there was concern about the impact of Labour’s policy on university funding in the THE survey, even among vice-chancellors who supported the abolition of fees. Asked whether they believed that a government that abolished fees in England would be able to fully make up the shortfall in university income from public funding, just 16 per cent of vice-chancellors said yes, and 84 per cent said no.

Several vice-chancellors who described the status quo as unsustainable also rejected Labour’s plans, calling for a system that recognised both the benefits to individuals and to society arising from higher education.

“A settlement that more explicitly recognised the balance in private and public benefits in higher education, and sought a similar balance in funding would be more defensible,” said one.

Iain Martin, vice-chancellor of Anglia Ruskin University, said that there was a need for “a very open and public debate” on higher education funding.

Professor Martin, who said that he advocated a “hybrid” system of direct public funding and graduate income-contingent loan payments, argued that vice-chancellors should not “pretend that the level of public anxiety about the current system is going to go away if we let things go quiet for a few months – because I do not think it is”.

“If you talk [to] students, parents, [the] broader community, whatever you think of the politics, Jeremy Corbyn hit a real public touchstone when he made the promise [to abolish fees]," Professor Martin said.

In a bid to safeguard the current system, ministers are said to be considering moves to lift the repayment threshold in line with earnings – as the government originally planned before imposing a freeze that retrospectively affected students who had already taken out loans. Also said to be under consideration within government is the possibility of pulling back from a rise in loan interest rates to a maximum of 6.1 per cent for graduates, scheduled for September. However, such a move would benefit only the higher earners who repay their loans in full and thus consequently begin to repay interest.

In the THE survey, one in five vice-chancellors said that they would support an increase in tuition fees beyond the rate of inflation.

Asked whether they believed that a government which abolished tuition fees would also impose student number controls – seen by some as a step that would affect the chances of poorer students making it to university – 92 per cent of vice-chancellors said yes.

Among vice-chancellors who thought the current system sustainable, one said: “Labour’s policy seems counter-intuitive if the aim is social mobility. It would have to lead to the imposition of student number controls and would equate to a transfer of resources to the middle class.”