“The final draft came back and all we had was a red circle around my boss’ name and an arrow that pointed to the front of the authorship list.”

This incident is seared into the memory of a pre-doctoral academic from India, who recently submitted a manuscript for publication. The researcher, who spoke to Times Higher Education on condition of anonymity, says that the principal investigator in the laboratory where he works full-time made a “minimal technical contribution” to the project in question, and merely corrected a few grammatical errors and spelling mistakes in the previous draft, before promoting himself to lead author.

“It’s unfair [but] I don’t really feel like I have much of choice. I am at a junior level…I need to get a bunch of papers out,” the junior academic says, explaining that publications are vital to secure a place on a PhD programme.

This story may sound familiar to many budding academics who are just starting out on the long, arduous path to scientific independence. But most experienced academics also have an authorship war story to tell. It might concern the head of department who insists on being named on every paper that comes out of their fiefdom, despite having had no input into most of them. It might concern the colleague who masterminded an entire research project but got no publication credit since they moved to another institution before it was completed. Or it might concern the PI of a collaborating lab, who used their greater seniority to make themselves the senior author on the paper, despite most of the project direction having been carried out by the more junior PI.

The reason all this matters so much, of course, is that journal articles are the currency of academic life, buying promotions, research grants and any number of scholarly accolades, such as plenary speaker invites and membership of prestigious societies. Moreover, in many disciplines, including most of the sciences, collaboration, at least within labs, is almost universal, meaning that papers almost always have more than one author. And, in terms of assigning individual credit, authorship order is often crucial – with the first (lead researcher) and last (senior author) positions being the greatest prizes.

The angst is only exacerbated by the fact that many journals do not have specific criteria on who is eligible to be an author, and what the ordering should be. It should therefore not be surprising that squabbles, complaints and outright feuds over authorship appear to be commonplace across the world.

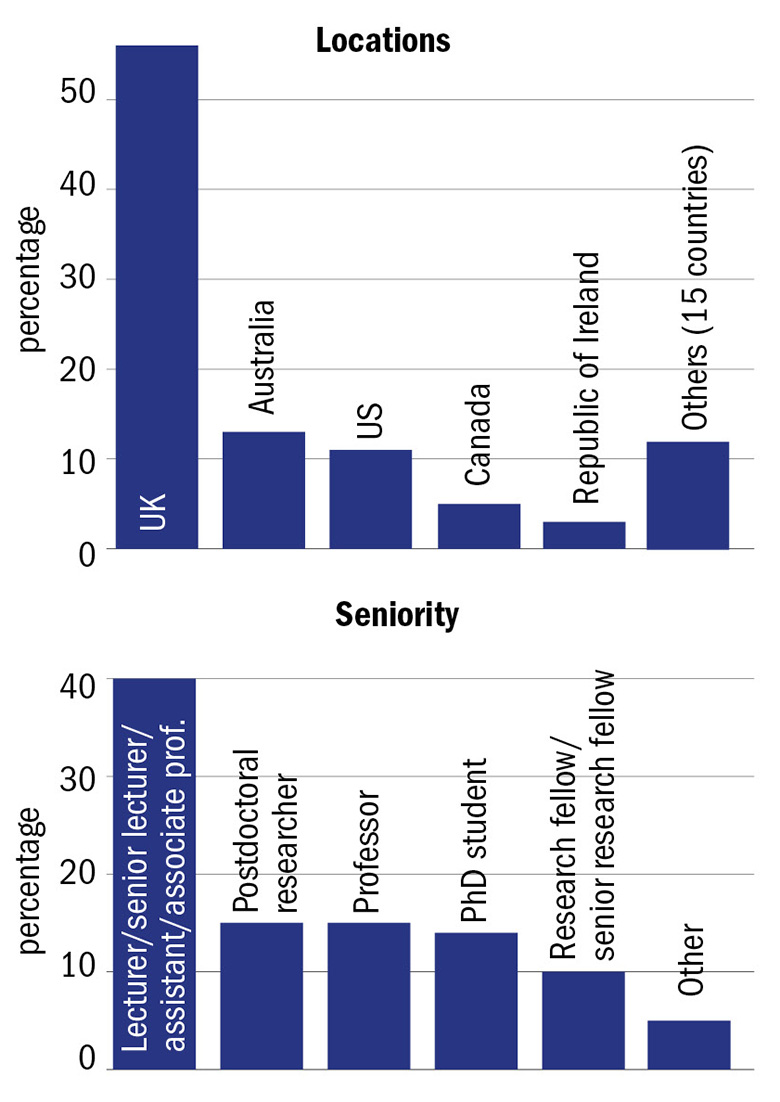

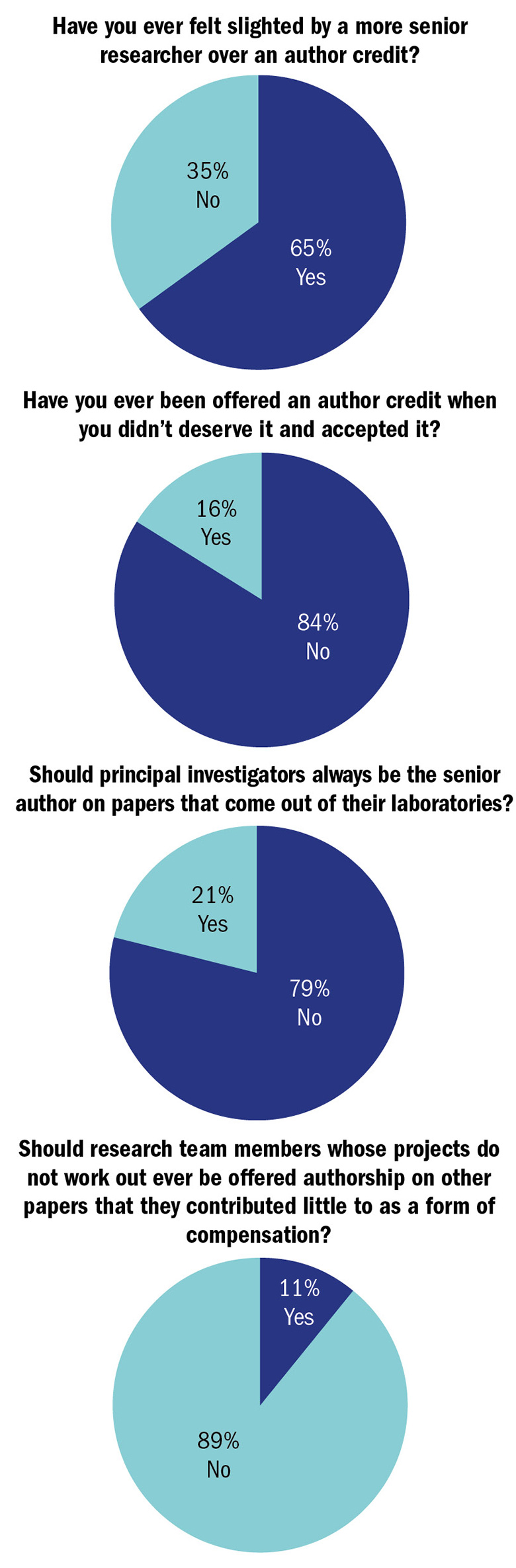

A straw poll conducted online by THE reveals how widespread authorship abuses are. Two-thirds of the 364 self-selecting respondents to the survey, from a wide range of countries and levels of seniority, report having felt slighted by a senior academic over an authorship credit, for instance. And one-third say that they had been offered an authorship credit when they did not deserve it – although only 16 per cent admit to accepting this type of offer.

Trisha Greenhalgh, professor of primary healthcare sciences at the University of Oxford, thinks that part of the problem lies with the system that many researchers are working in. “There is an awful lot of pressure on academics…Unless you meet the metrics, you might not be promoted and you might not keep your job, and that means there is an incentive for academics to, frankly, abuse the juniors,” she says.

Greenhalgh, who is a vocal advocate for fair dealing over authorship practices and has previously suggested that academics pledge a version of the Hippocratic oath regarding ethical behaviour, knows only too well how early career researchers can be manipulated by their seniors. She once had to “rescue” a postdoctoral scientist she knew, who was suffering at the hands of someone manipulating the system.

The young academic, who had a research council fellowship, was headhunted by a prestigious institution in London. But when they arrived, the job did not turn out to be what they expected, she says. They were not given any time to work on their own research and, instead, spent their days writing grant applications and journal articles for other people in the department, which left them increasingly miserable and stressed.

Greenhalgh helped the person to secure a position elsewhere, which she says was possible thanks to her seniority and contacts. But it still proved difficult, partly because the supervisor threatened not to provide a reference, nor include the postdoc as an author on the papers that they had worked on.

“It was straightforward exploitation: in fact, it was slave labour, because the research council was paying this person, not the university,” says Greenhalgh. The individual, who has since gone on to be successful in their field, nearly quit science as a result of their treatment and needed a “huge amount of nurturing, support and psychological repair” to carry on, she adds.

“We shouldn’t be eating our young. Somehow the moral behaviour of academics is being overshadowed by the performance against metrics,” she says. But such behaviour, she adds, is positively encouraged by the status-obsessed culture in some universities.

Where and who: the respondents

Authorship has been a fraught issue in academia for many years. But the pressures on scholars are increasing, says Brian Nosek, a professor in the department of psychology at the University of Virginia, and the executive director of the Centre for Open Science.

“There are more researchers than academic jobs. The competition for those slots is very intense. As a consequence, the pressures for achieving authorship are higher,” he explains.

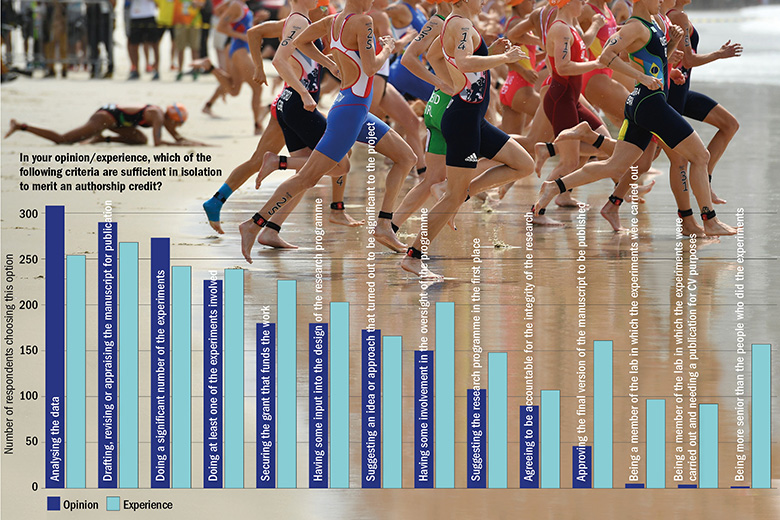

THE’s survey flags up how a considerable gap can open up between the criteria that academics think should qualify someone for authorship and the criteria that, in practice, do so. The latter list is somewhat longer. For instance, just five respondents think that simply being a member of the laboratory where the research took place should be sufficient to merit an authorship credit. However, 97 people report that, in practice, they have seen authorship awarded for so little. And just two respondents think that being more senior than the people who did the experiments should merit authorship, but 157 – 44 per cent of respondents – have seen this criterion apply in practice.

But even agreeing on the “shoulds” is not easy, according to Nosek. This is because “research is difficult, unpredictable and highly variable”. As well as writing up the paper, other important contributions include conceptualising the ideas, designing and carrying out the research, analysing the data and interpreting the evidence. “Sometimes, that whole sequence can be done within days or weeks; other times it takes years,” Nosek says. In the life sciences, the process can involve up to 200 people, he adds.

Some organisations and journals have sought to quantify exactly what warrants an authorship credit. The most well known description is the list of authorship criteria drawn up by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, which specifies that academics need to meet four criteria to put their name to research.

According to the guidelines, would-be authors must have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or collected, analysed or interpreted the data; drafted or revised the manuscript; approved the final version for publication; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

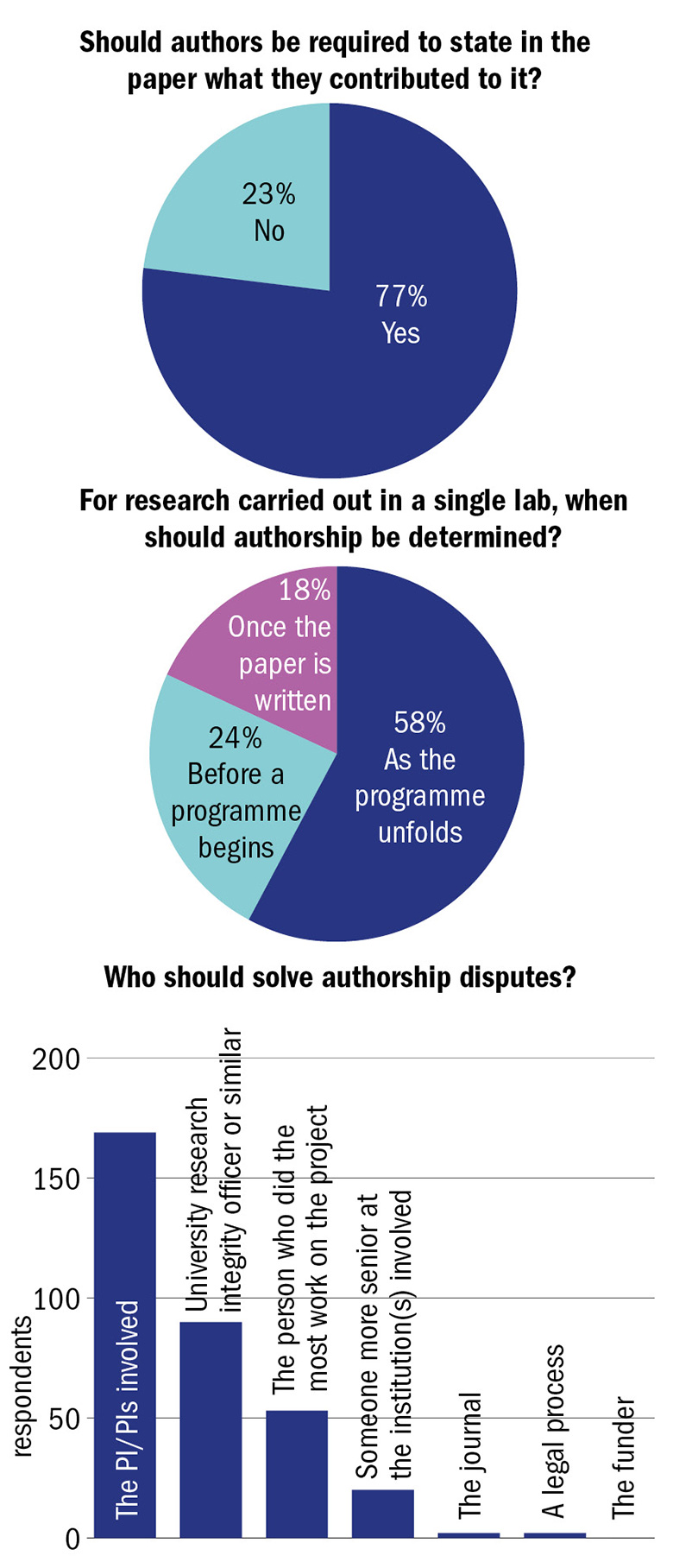

When it comes to adjudicating disputes about authorship, the majority of the respondents to THE’s survey think that this should be the responsibility of the PIs involved. Many believe that a university-employed research integrity officer can also help, but very few think that funders, lawyers or journals have any role to play. Nevertheless, many journals in biomedical fields use the ICMJE’s criteria as the basis of their own specific authorship policies. Interestingly, there is no mention in any of these policies of being the person who secures the funding for the research project: cited by 180 respondents to THE’s survey as a legitimate criterion for authorship.

Queries about authorship are frequently received by the Committee on Publication Ethics, a UK-based membership organisation that offers ethical advice to editors and publishers. The organisation’s 2014 white paper, “What constitutes authorship?”, pulls together the standards and guidelines published by learned societies and publishers and offers answers on common authorship conundrums. The thread that runs through the different listed policies is that an author must have made a substantial or significant contribution to the work and be accountable for all or part of it.

But Nosek thinks it unlikely that there will ever be “a bright line standard” on what constitutes the earning of authorship rights. “A more effective solution, I think, is [for] the emerging norm to explicitly identify what contributions each author made.”

Author! Author!: A fair deal?

The publishers of Nature have been asking researchers to submit author contribution statements on a voluntary basis since 1999. In 2009, it was made mandatory. According to Sowmya Swaminathan, head of editorial policy at Nature Research, the level of detail that authors go into usually reflects disciplinary norms. Life scientists tend to go into an “incredibly high level of detail”, giving specific attributions for specific experiments, for example.

“From our point of view, author statements address the issue of credit and accountability…and help discourage inappropriate practices such as ghost or gift authorship,” Swaminathan says. Ghost authors are those who have done enough to earn an authorship credit but are not listed, often for reasons of perception, such as when a drug company has had an input into a study validating one of its products. Gift authors are those who have not done enough to merit inclusion, but who are included in an attempt to curry favour with them, to acknowledge an ongoing relationship, or to give the paper a greater sense of legitimacy.

Of the respondents to THE’s survey, 77 per cent agree that authors should be required to state their contributions to papers, mostly for reasons of transparency, accountability and giving credit where it is due. In the view of a US-based assistant professor, stating authorship contributions is “essential for accountability, and for giving credit in cases where a subset of the authors did a disproportionate amount of work”. For one UK-based research fellow, author statements are necessary to “give a clear indication of who deserves credit for different aspects of the project and who has responsibility for the work”. Another UK research fellow agrees, noting: “I worked for one professor who used to give…papers to his favourite [junior staff member] and then claim that because he had done a substantive rewrite (which wasn’t true) he should be first author.”

According to an Australian postdoctoral fellow, authorship statements would also help to compensate for the varying disciplinary norms around authorship. “The sciences are full of papers where bringing somebody a cup of tea is good enough to get authorship,” the postdoc says, “while in the humanities a research assistant who spends days in the archives still doesn’t get any credit – and then gets screwed when competing for research funds because ignorant scientists who don’t know the publishing norms of other disciplines view them as underproductive.”

Another Australian postdoc suggests that the authorship statements could even be scrutinised by the paper’s reviewers, who could suggest changes to the authorship order “to safeguard junior researchers who may have been exploited”.

But other survey respondents support authorship statements only with reservations. One UK lecturer, for instance, suggests that it “won’t solve the problem. Clear guidelines and early planning are more important.” And an Italian postdoc notes that “it is not always easy to describe the contribution of the authors, especially when the contributions were small but multiple and significant”. A US professor adds that allocating credit is particularly difficult in “successful teams”. And a UK lecturer worries that author statements “undermine the nature of collaboration…with people trying to dominate”.

Some respondents also note that where honesty is lacking, author statements will change little. A UK lecturer fears that “coasters will inflate/imagine work they did”. A US assistant professor notes that statements of contribution are “usually under the control of the first or corresponding author, and may be disputed”, so “do not necessarily reflect what the contributions truly were”. A UK PhD student agrees, adding that their PI “has added fake contributions for people who have no right to be on [the] paper”. And a Canada-based professor adds: “Honestly, many people lie about what they did. Reporting does not always equate with the truth.”

Several respondents also assert that “no one reads” author statements. “It is just something else that a dysfunctional collaboration can argue about,” says a US-based professor.

Creditworthy: the key criteria for authorship

View/download hi-res version

Nature journals also have a policy that sets out the responsibilities of corresponding authors: usually the senior (last) author of the paper, to whom queries should be addressed. But the journal has sought to avoid being too prescriptive “about what it means to be an author”, Swaminathan says, adding that this is because it is not realistic to expect that the norm in one discipline will work for another.

“In the past decade and more, as science has advanced, we have seen [many] technological innovations and research has become more interdisciplinary, international and collaborative. All of those aspects of authorship are challenging for everyone,” she says.

In cell biology, for example, the number of authors listed on a paper has swelled. “When I started [at Nature] in 2003, you would see papers with fewer than 10 authors. Now, that has become increasingly rare because the papers are so multifaceted. Not only are the research questions complex, these papers are now employing a range of experimental approaches and models, so it really requires a collaborative approach,” she adds.

Author numbers on physics papers have also soared, with publications coming out of the Large Hadron Collider at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (Cern) crediting thousands. The 5,154-strong author list for one recent paper that described the size of the Higgs boson, published in Physical Review Letters in 2015, ran to 24 pages, while the research itself, plus references, spanned only nine.

Long author lists can cause their own problems for those who need publications to advance their careers, according to Philippe Froguel, chair of genomic medicine at Imperial College London. He says that the current trend in genetics is to work in multinational consortia that publish papers with hundreds of authors. This is often good news for senior scientists’ h-indices: a hybrid bibliometric measure of the quality and quantity of their publications. But it also means that the contributions that junior scientists make to projects are overlooked, since if they are not in the first three or four authors it is difficult for them to claim an active role, Froguel says. “When they go for promotion, the panels say: ‘What did this person in the middle of 200 actually do?’”

These huge projects, which can involve as many as 50 research groups, usually have a steering committee that tends to agree authorship protocol in advance, with each team assigned a number of spots on the author list. But there are times when names are added at the last minute, or when worthy people are unfairly denied senior authorship, he says.

“These kinds of big boards are complex to pilot,” he says, likening those in charge to the “don[s] of the mafia”. He continues: “If there are 280 people signing a paper, I would say that for 270 it is fair…but for the first five and last five [the most significant positions], it is, in fact, decided by a couple of people.” He knows of people who have been “blacklisted” from taking part in the next consortia’s study after objecting to authorship decisions by the mafia dons.

Would you credit it?: Where it’s due

Social scientists are also grappling with the issues that multiple authorship presents. In a recent survey by publisher Taylor and Francis, 74 per cent of respondents working in the humanities and social sciences reported that papers in their field typically have two or more authors.

Bruce Macfarlane, a professor of higher education and head of the School of Education at the University of Bristol, who authored the report containing the survey, has studied authorship practices around the world.

“Academics in China, for example, receive a very low base salary, but can get substantial additional payments for every publication in a high impact factor journal,” he tells THE. “If you are a first author, the rewards are greater. This can lead to a lot of authorship abuses.”

It is also common for researchers in some parts of the world to credit their doctoral supervisors in papers they publish even years later, into which the former supervisor has had no substantial input. Macfarlane previously worked at the University of Hong Kong, where his research among education academics in the city state revealed that one-fifth thought that this should always happen.

Macfarlane explains that the reasons for gifting authorship in China have a lot to do with “a feeling of indebtedness and respect for supervisors as teachers”; part of the cultural practice of guanxi, which roughly translates as “relationship”, and revolves around building connections with people for future reciprocal benefit.

In China, as well as Japan, it can also be common to over-credit junior members of a research team, in an attempt to boost their careers, Macfarlane adds.

With such cultural cross-currents only adding to the complexity of the debate, it seems likely that authorship will continue to be scrapped over for as long as research papers continue to be the principal means by which academics are judged. Confronted with the results of THE’s straw poll, Peter Lawrence, Medical Research Council emeritus scientist in the department of zoology at the University of Cambridge, says that the main message is that “no one has a clear idea of the ethics or what is proper behaviour. There is no common agreement about what is morally appropriate; people have all kinds of different views and these are usually self-serving.”

Some might argue that this is because most academics do not give ethical issues enough thought. But even if they did, it is hard to see how consensus could be reached on anything more than broad, high-level principles. There will always be scope for disagreement over the rights and wrongs of specific, high-stakes cases. As Nosek puts it: “Most academics spend their time worrying about getting the research done and make decisions about authorship relatively intuitively…There will never be a simple solution.”

后记

Print headline: All present and correct?