In the early 1980s, at the height of the Cold War, the eminent cartographer J. B. Harley transformed the study of maps in a series of brilliant articles deconstructing the presumptions that cartography was a scientific, objective study of physical space. Having read his Derrida, Foucault and Barthes, Harley argued that all maps were shaped by prevailing social, political and ideological factors and represented the world according to the vested interests of those who made or paid for them.

Most scholars assumed that Harley’s innovation came from reading post-structuralist critical theory, but John Davies and Alexander Kent’s brilliant Red Atlas, on the extraordinary Soviet project to map the world from the 1940s until the empire’s collapse in 1989, suggests that Harley and his disciples were also responding to how state power during this particular confrontational period appropriated cartography to further its political ideology.

Harley would have admired this book for many reasons: its scholarly detail, the light touch of its critical argument, the lavishness of its illustrations, its dry humour and, above all, the remarkable and definitive story it tells of what the authors call “the world’s largest mapping endeavour”, a crucial yet neglected moment in 20th-century cartography due to the Soviet Union’s demise and the strict secrecy surrounding its map-making. The book begins with a startling claim: wherever you live on the planet, it is likely to have been mapped in detail by the Soviet Union. Like all centralised states, it had a keen interest in mapping its emerging empire and defining its borders after the Bolshevik Revolution.

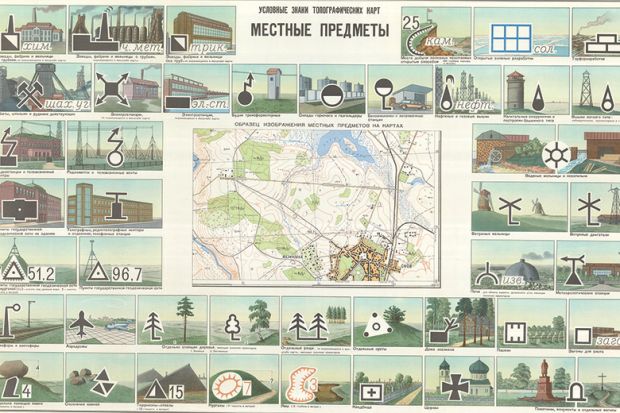

Drawing on Albrecht Penck’s International Map of the World (begun in 1913), Lenin ordered military topographic maps based on photogrammetry. During the Second World War, Stalin created the Military Topographic Directorate of the General Staff of the Soviet Army to create maps of different parts of the globe that, over the next 50 years, would total more than 1 million. The scale and detail of the maps took on even greater accuracy with the launch of the Zenit satellites in 1962. From this point until 1989 the Soviets mapped about 2,000 cities worldwide (not including Russia), about 120 in the US and 100 in the UK, most at a scale of 1:25,000, but some as detailed as 1:5,000.

The book considers both internal and external Soviet mapping, showing how military maps of Russia were kept more secret and produced on much larger scales than maps for public consumption, which were often doctored or distorted on the assumption that Western powers could obtain them and use them for military intelligence. Some of the authors’ most fascinating research involves asking how the external maps were made and for what ends. They estimate that thousands of workers were involved in compiling these maps (including women), gathering material from official state maps (in the UK the Ordnance Survey, and in the US its Geological Service), but of course these maps were also censored. This created a looking-glass world in which both sides were trying to second-guess the other’s military capabilities in a story that often reads like a cartographic episode written by John le Carré. The authors conclude that the maps were made with a view to conventional military campaigns, but that as they were not exclusively concerned with the location of military installations, they were also “intended to support civil administration after a successful coup”, giving a sense of the political confidence of the Soviet regime at its zenith.

Where the book really excels is in its extraordinary detail in interpreting individual maps, all produced in Cyrillic, which remains part of their attraction for those of us in the West who “are looking at our own homes through the artistry of our adversaries”. Davies and Kent trace changing scales, symbols, topography, printing, even lettering, while never losing sight of the human dimensions of the map’s production. Digging through memoirs plus declassified military and intelligence papers, they reveal just how local information supplemented that from officially printed maps, often with comical effect. They discover that in Sweden in the early 1980s “Soviet diplomats would arrange picnics in places of strategic interest” and befriend local labourers working on sensitive military works. One Soviet spy lounging on the beach “started a conversation with an excavator driver” digging trenches for minefields. Unfortunately for the Soviets, “there was a Swedish secret agent on the beach too. He heard the whole conversation.”

Davies and Kent are also alive to the limitations of the Soviet maps resulting from things “lost in translation”, as they put it. On English maps they note that place names are rendered phonetically in Cyrillic, so Gloucester is transliterated as “Gloster”, which they conclude “may be helpful if the map user needs to ask directions from a native, but would be unhelpful if trying to navigate using road signs”. Such issues led to unintentionally amusing confusion: on the Soviet map of London, Her Majesty’s Theatre in the West End is identified in Cyrillic as “Residence of the Queen and Prime Minister”.

This did not prevent the maps from having a use value even beyond the collapse of the Soviet regime. The book’s final chapter returns to le Carré territory in revealing how the maps were sold off by unscrupulous Soviet officers desperate for foreign currency. One delightful story involved “a briefcase filled with $250,000 in cash” exchanged for crates of thousands of maps. These maps found their way into the hands of not only avid map dealers but also Western military intelligence. By 2001, American military pilots were using Russian maps of Afghanistan from the 1980s in their bombing campaigns against the Taliban, because they were quite simply superior to anything held by US intelligence.

The Red Atlas is the best kind of cartographic history: scrupulously researched across the fields of map-making as well as social history, telling in its detail yet alive to the human act of map-making, and beautifully reproduced by Chicago University Press. It also takes us deftly beyond J. B. Harley’s thesis that maps are simply driven by ideology. These Soviet maps, we read, “have an artisanal quality” that suggests their makers “were thinking about more than just providing Soviet military officers with maps for marching”. As in so many cases where cartography gives us an unparalleled access to the past, the Soviet empire has gone, but its maps have endured, a silent rebuke perhaps to the folly of imperial aspiration that produced them. “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” as Shelley’s Ozymandias proclaimed.

Jerry Brotton is professor of Renaissance studies at Queen Mary University of London and the author of A History of the World in Twelve Maps (2012).

The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World

By John Davies and Alexander J. Kent

University of Chicago Press, 272pp, £26.50

ISBN 9780226389578

Published 17 October 2017

The authors

John Davies, editor of Sheetlines, the journal of the Charles Close Society for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps, is an independent scholar. When he left school in Bradford in 1960, he says, it was “a prosperous city with plentiful opportunities”, where “going to university was not generally considered necessary”. Nearly 60 years later, and retired from a career in information systems, he believes that “a sense of adventure, curiosity and sufficient native wit has probably compensated for the lack of formal education”.

A lifelong map enthusiast, Davies first “encountered Soviet mapping while working in Latvia in the early 2000s”, and this “sparked…the urge to investigate the Soviet global cartographic project. We have dubbed these Soviet maps ‘the Wikipedia of the day’, in that the cartographers depicted on the maps everything they could discover about a place, without needing to know who would be using them.” Davies now runs the website Sovietmaps.com.

Alexander J. Kent, reader in cartography and geographical information science at Canterbury Christ Church University, grew up in the small fishing town of Deal, Kent, and studied geography and cartography at Oxford Brookes University. “Growing up by the sea”, he reflects, “broadens your horizons and maps offer the possibility of real or imagined journeys, so ever since I first encountered them on day trips to France I began to wonder why foreign maps just ‘look different’ ”.

With a father in the Royal Marines, Kent also grew up with “a fascination for military history”, yet it was his “discovery of an ‘Aladdin’s Cave’ ” of Soviet maps in a shop in Almaty in Kazakhstan while on a trekking holiday in 2001 that led him to explore them further.

Editor of The Cartographic Journal, Kent is also president of the British Cartographic Society.

Matthew Reisz

后记

Print headline: Before Google Street View, there was the USSR