One of the mantras of those who support the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union has been that the country has a ready-made alternative global network to tap into for trade, collaboration and other benefits: the Commonwealth.

But, with a little over a year to go until “Brexit Day”, could this undeniably diverse collection of 52 nations really offer an alternative to the huge pool of talent and resources right on the country’s doorstep when it comes to higher education and research? Or is the Commonwealth actually more useful for building the capacity of emerging nations?

Such questions are likely to form part of the background to discussions at the latest Conference of Commonwealth Education Ministers, taking place in Fiji this month, ahead of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting – the first since the Brexit vote – in London in April.

To mark these events, Times Higher Education has analysed the data on higher education in the Commonwealth to assess the current standing of the nations’ universities, how they are collaborating and whether their common ties of language and culture provide a basis for even greater links in the 21st century.

Although they make up only a small proportion of all higher education institutions in member nations, the Commonwealth universities in the THE World University Rankings make up nearly a quarter of the 1,000-strong list. And while more than half of all Commonwealth institutions in the ranking are from the UK (93), Australia (35) or Canada (26), the data still provide a good starting point for assessing key characteristics of Commonwealth universities.

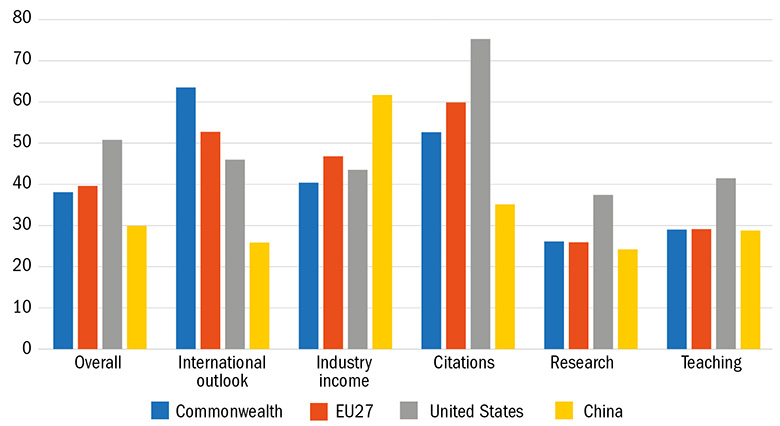

Comparing their scores across the five main “pillars” that constitute the ranking – teaching, research, citation impact, industry income and international outlook – with the rest of the world gives some intriguing initial results.

Commonwealth universities have a slightly better overall points score than the rest of the world and also enjoy a lead in terms of citation impact, a proxy for research quality. However, their lead on international outlook is much more significant, and they outscore the US, the rest of the EU and the major emerging higher education system of China (see graph 1, below).

Graph 1: Average ranking pillar scores

For Joanna Newman, secretary general of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, such indicators reflect deep ties that the nations’ universities have shared for decades, enabling the flow of students, staff and ideas. These include obvious common characteristics such as the use of English, but also factors such as similar education systems that produce mutually recognisable qualifications.

“It absolutely reflects the unique nature of the Commonwealth’s long history of collaboration and…shared values, networks, relationships, law, language and qualifications,” says Newman. “There are decades’ worth of academics who have travelled to receive their education from one Commonwealth country or another. It is much easier to travel across the Commonwealth because you’re speaking the same language and your degrees are recognised.”

Newman points out that the links are further enhanced by graduates returning home, maintaining ties with their university and developing them as they further their careers. This can foster important links across many different sectors, including politics and industry. But it has particularly clear benefits for academia and research collaboration.

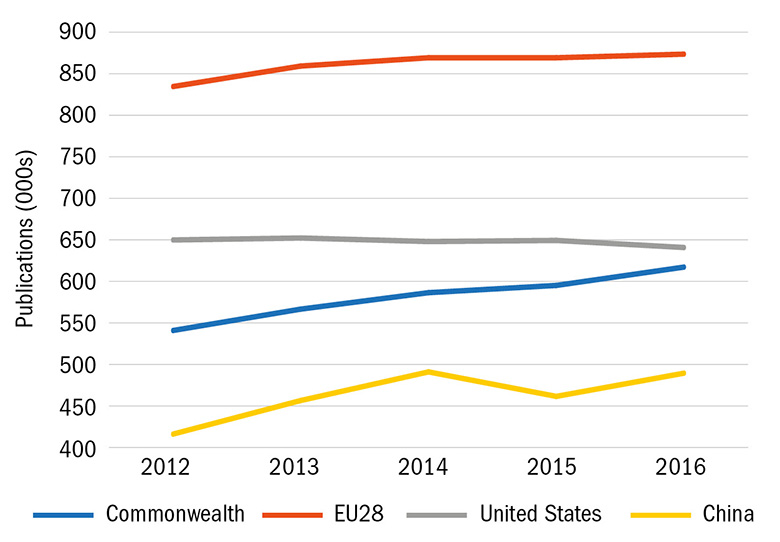

According to data taken from Elsevier’s Scopus database of published research – which allows an analysis of statistics underlying more institutions than those in the rankings – the share of scholarship produced in the Commonwealth that includes international collaboration is very similar to the share produced in the EU (here the UK is included in both groups), and has also been growing at a similar rate. However, in terms of pure research volume, the Commonwealth is a fair way behind the EU: between 2012 and 2016 the former produced about 2.9 million pieces of research compared with the EU’s 4.3 million (the US on its own also had a higher output of 3.2 million) – see graph 2, below.

Graph 2 – output and international collaboration

Scholarly output, 2012 to 2016

% of research featuring international collaboration

Source: Elsevier/SciVal

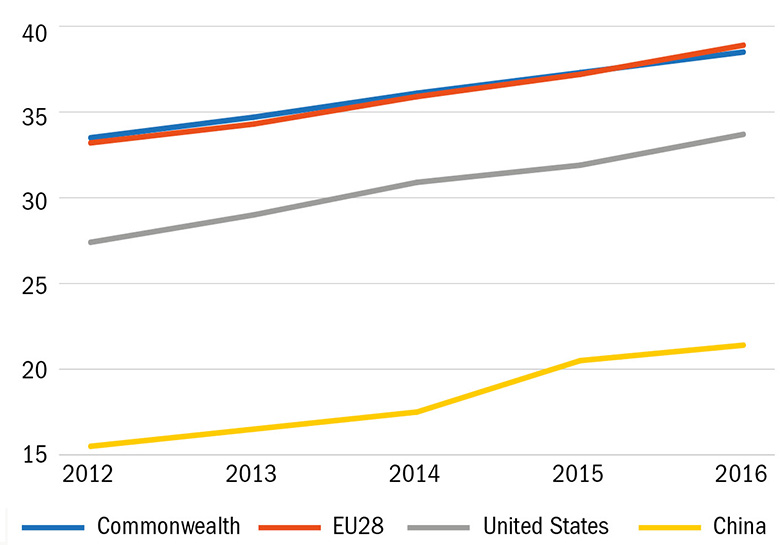

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the list of the nations in the group producing the most research between 2012 and 2016 is headed by the UK, but India grew its output over the period by almost 37 per cent, leaving clear water between it and the nations in third and fourth place for volume, Canada and Australia (see graph 3, below).

Graph 3: Volume of research published 2012-2016

Note: The number at the end of the bars is percentage growth

Source: Elsevier/SciVal

But what is collaboration like within the Commonwealth, and are links within the bloc as important to its members as, say, connections with leading world research powers outside it?

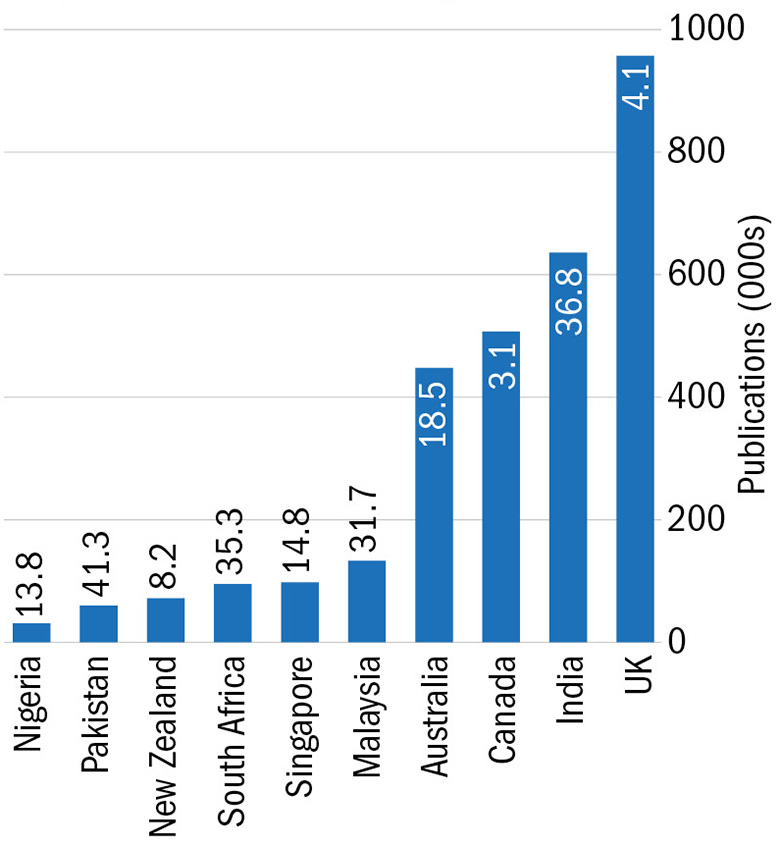

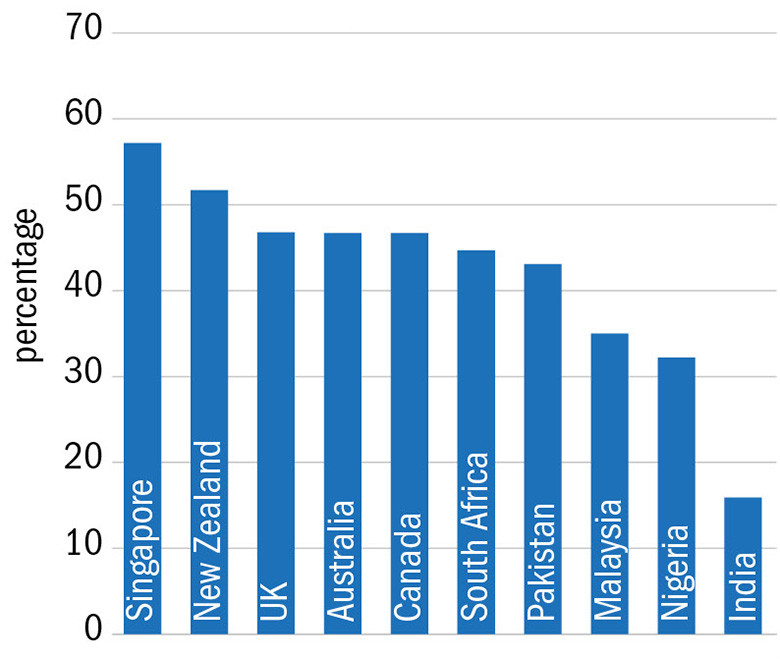

On international collaboration, India is a long way behind not just the developed Commonwealth nations but also emerging research nations with large volumes of scholarship, such as Malaysia, South Africa and Nigeria. For instance, in 2016, almost 48 per cent of research with a South African author had at least one overseas co-author. In India, the figure was 16 per cent (see graph 4, below).

Graph 4: Proportion of Commonwealth publications with international collaboration, 2012 to 2016

Source: Elsevier/SciVal

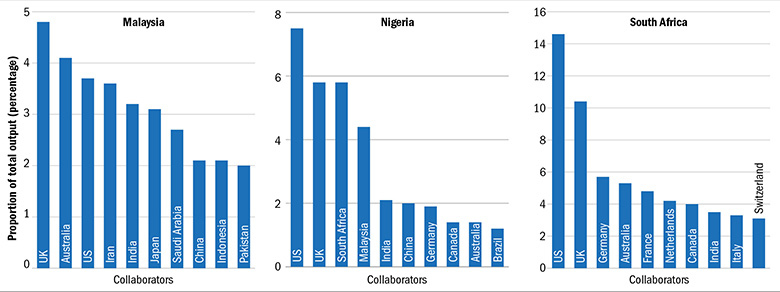

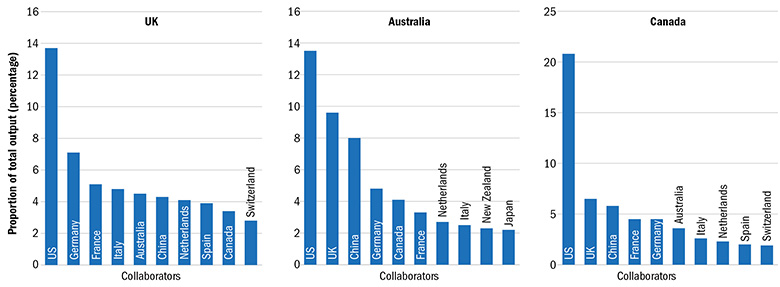

Digging deeper into the data reveals some very interesting patterns. Except for India, emerging Commonwealth countries in the top 10 for output tend to collaborate with more Commonwealth countries than the developed Commonwealth nations do. For instance, four out of the top 10 collaborators with South Africa and Malaysia are from the Commonwealth and, for Nigeria, this figure is six. The UK and Canada have just two collaborators from the Commonwealth in their top 10s, and Australia has three (naturally, all three of these countries figure highly among each other’s collaborators. The extra country with which Australia often collaborates is New Zealand).

For Malaysian academics, Australian and UK researchers are the top overseas collaborative partners, but for all other Commonwealth nations that produced more than 30,000 publications between 2012 and 2016, the top collaborator is the US (see graph 5, below).

Graph 5: Top commonwealth collaborators

Source: Elsevier/SciVal

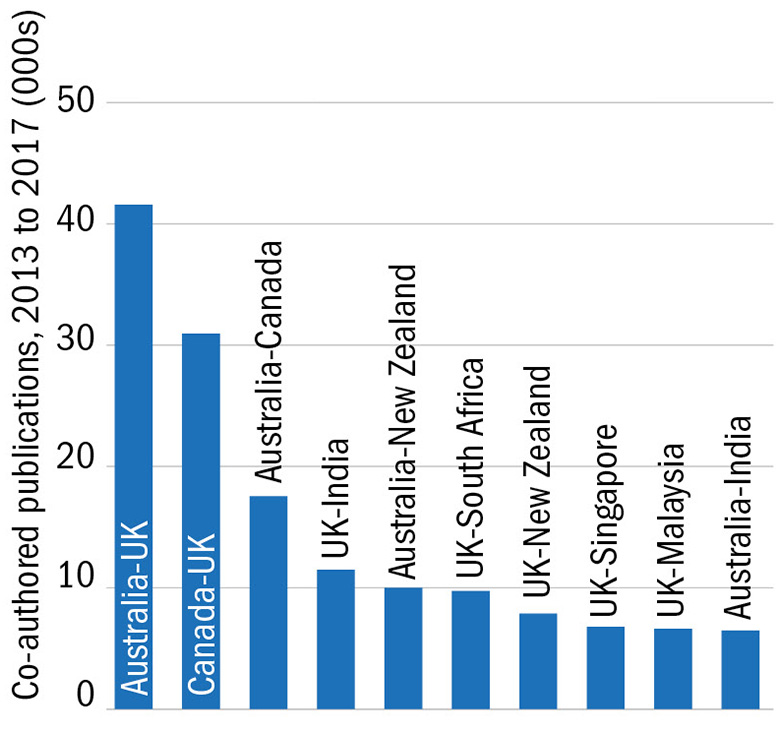

Of the established research nations, Australia has the strongest links with its Commonwealth partners. Its collaborations with the UK account for the largest number of papers co-produced by Commonwealth nations (see graph 6, below). Canada’s collaborative output is, unsurprisingly, dominated by its near neighbour, the US (accounting for 21 per cent of all its cross-border research), while the UK’s ties to both Europe and the US are very clear.

Graph 6: Top 10 Commonwealth collaborations, 2013 to 2017

Source: Elsevier/SciVal

For Simon Marginson, director of the Centre for Global Higher Education at the UCL Institute of Education, there is “no doubt that the Commonwealth is an umbrella that fosters research collaboration, and has positive developmental implications for emerging countries”.

However, while links to other Commonwealth nations such as the UK, Australia, Singapore and India are a “boon” of membership for emerging nations such as Malaysia and Nigeria, they also carry dangers, especially if their reliance on such connections “leads to a narrow set of global links in the long run. Research is a global system and it’s important to keep lines out to all the established players…new stars…and other emerging systems”.

And while some in the UK might point to the Commonwealth as a ready-made source of research networks to replace existing links with European institutions, should the UK fail to negotiate the continuing access to the EU’s research programmes that it wants post-Brexit, Marginson thinks that taking this attitude would be “unwise…not only because the scale [of the Commonwealth] is smaller [but also because] the UK gains more in terms of quality and world competitiveness by networking with peers or near peers in Europe than with emerging countries”.

Newman also emphasises that there is no mileage in the UK cutting its important research links to its near neighbours, and that any strengthening of the Commonwealth should take place at the same time as maintaining links with the EU.

But she agrees that Brexit has presented an opportunity for greater intra-Commonwealth collaboration, not least because the UK “will be warmer towards collaborating [in] and funding programmes. It is clearly in the UK’s interest to collaborate and strengthen higher education systems in emerging countries that will have powerful research institutions in the future”. She adds that the geographic spread of the Commonwealth has made it the “most diverse bloc of countries across the world”, something that, in terms of research power, could enable it to “be as powerful as the EU, or even more powerful, in years to come”.

One way that the UK has already been using its influence to help emerging countries develop their research capacity is through the Global Challenges Research Fund, the five-year £1.5 billion programme that uses money earmarked for international development to fund research projects with the developing world. One of its stated aims is to help “strengthen capacity for research and innovation” in developing nations and, although it is not confined to Commonwealth countries, much of the money will inevitably help nations within the network because of established academic links.

However, many question whether the fund is a good way to increase research capacity in the developing world, given that all the funding is directed by the UK. Ben Prasadam-Halls, director of programmes at the ACU, says that while the fund is a “great programme” it may have the potential to “crowd out” collaboration between the developing nations themselves. And Marginson points out that “collaboration develops best when the agency of all partners is growing, in shared schemes in which all countries have nominal equivalence, like the European research programmes, rather than dependency relationships setting the scene”.

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is an institution with more experience than most of fostering collaboration between nations in the developing world. It has also just taken on an even more hands-on role by assuming management of Medical Research Council research units in the Gambia (which has just rejoined the Commonwealth) and Uganda. Anne Mills, deputy director of the school, says that one obstacle is the sometimes clashing “agendas” that often lie behind Western nations’ funding programmes to boost developing world research.

“This can lead to a position that is very fragmented and [where] capacity is…made rather more difficult to sustain by all these competing flows of funding into the country,” she says.

Mills points to attempts by funders such as the Wellcome Trust to shift towards a model whereby money is managed within Africa rather than through a “top down” approach. However, she adds that although the Global Challenges Research Fund presents a “huge challenge of allocation and coordination”, this was “recognised” on the UK side. “We’ll just have to see how successful the coordination mechanisms are going to be,” she adds.

According to the ACU, a key issue that will be explored in Fiji is how to strengthen research links between some of the universities in emerging countries that have been affected most acutely by climate change and by natural disasters such as the hurricanes that wrought destruction in the Caribbean last year.

Alex Wright, senior policy officer at the ACU, who is helping with its work for Fiji, says that such a research network would focus “on the adaptation and application of research” and how “universities can play a tangible role in helping communities and economies prepare and respond to climate events”. This is a “good example of how the Commonwealth can build really concrete collaborations” between smaller, emerging research nations that also have a “unique take on a global issue”, he adds.

But what do institutions in these smaller and emerging Commonwealth countries see as the best ways to help them increase research capacity and mutual links? Barnabas Nawangwe, vice-chancellor of Uganda’s Makerere University, one of the most successful research institutions in sub-Saharan Africa, says that the Commonwealth is well placed to help grow research collaboration in several ways. These include travel grants to enable researchers to move between Commonwealth countries, funds for “multi-country research projects on issues of common concern” and conferences on specific themes.

He emphasises that collaboration between universities in the Commonwealth is “very important” because it enables researchers to use the “unique” features of the different countries to “ their findings with those of their colleagues, making the research richer and more comprehensive”.

Dhanjay Jhurry, vice-chancellor of the University of Mauritius, who sits on the ACU’s governing council, also suggests that “the development of research consortia” linked to specific issues is a good step forward in terms of increasing collaboration between Commonwealth institutions. “There is also a need for enhanced technology transfer in the less developed world, which the Commonwealth could help develop”, he adds, perhaps through aiding the commercialisation of research findings.

Jhurry acknowledges that the movement of students and academic staff is already facilitated by ACU programmes, including the Commonwealth Scholarship and Fellowship Plan, established by Commonwealth education ministers at their first conference in 1959 to support graduate students. But he adds that what may be needed now is a Commonwealth “mechanism” for funding research partnerships, suggesting that “the EU model could be emulated”.

But the prospects of a pan-Commonwealth research funding scheme seem remote. One bone of contention would be the distribution of a funding pot to which the UK, Canada and Australia would presumably be expected to contribute the most.

Marginson points out that the much greater research prowess of the UK means that although there would be “gains to be made” for the country “through stronger links with particular research programmes in particular Commonwealth nations, there’s limited scope for the kind of collaboration that drives improved performance on a macro-scale”.

On the positive side, though, he adds that building additional Commonwealth links would not take long “because of cultural common ground and shared biographies. Many Commonwealth researchers have been educated in UK universities or spent significant time in them”.

And, for Newman, there is certainly “an opportunity…to create new research funds between [Commonwealth] countries that have significant research funding of their own...and there is a clear interest in doing so, I think, for most of those countries”.

She hints that the UK will have a chance to create the momentum on such initiatives once it takes over the two-year chairmanship of the Commonwealth at the London conference. And if the UK does fail to secure continuing access to EU framework programmes, an alternative scheme involving the likes of Canada, Australia and New Zealand may become very appealing – even if it could never amount to a full replacement.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: Calling on the might of the clan