William Overholt, a senior fellow at Harvard University, doesn’t just visit or study Asian countries; he “wanders around” them. He also attacks those “Manichaeans” who divide the world and many subjects into good and bad – while doing just that himself.

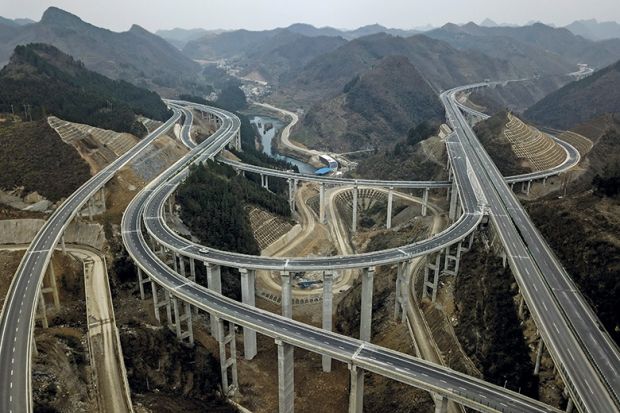

In his new book, no slight to him is ignored, whether from Western governments, entire professions such as academic China specialists or even journals. Some economies are praised – chiefly Taiwan, South Korea and, of course, China – for their “Asian miracles”. Others – “democracies” such as India, Japan and the US, where, he asserts, much of the infrastructure is inferior to China’s – are damned.

The subject of Overholt’s book is the “Asia” or “China model”, which, he says, sensible developing countries should emulate. He calls it a “political-economic strategy for achieving rapid development, social stability and national security based on an initial obsessive priority for economic growth. It comprises tough imposition of radical economic changes by an authoritarian leadership, which is motivated by leaders fearful of economic collapse and supported by a population fearful of catastrophic social collapse…It ignores the shibboleths of Western theories of economic and political development and provides the fastest way yet discovered to improve the livelihoods of a society’s peoples, stabilize its domestic politics, and enhance its national security and development.”

One of the errors of the Manichaeans, writes Overholt, is their conviction that democracy is always the best path, in the initial stages of development and for the future. He urges them to contrast Mumbai with Shanghai. In “democratic” India, he contends, “human conditions” are far inferior to those in China. The malnourished 12-year-old girl whose mother died in childbirth, who has never seen a toilet and who will be forced to marry an old man, will be able to vote, “but is that really what is important to her human dignity?”

In China, Overholt writes, women now work in factories – although with male bosses – and often enjoy higher educations. (He doesn’t say that many of them left the countryside because there was no work.)

What we see in China, he emphasises, is a healthier society, where people are taller, and more children survive and are educated. Overholt admires Orville Schell and John Delury’s Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-first Century (2013), but that book states flatly that, as of 2010, “five hundred million people [almost half the population] continued to live in grinding poverty”.

More strikingly, Overholt proposes an Asian model in which people, having more information, speak their minds, protests are permitted “within limits” and the press is allowed some freedom. This will come as news to the admirers of Liu Xiaobo, China’s only Nobel Peace prizewinner, sentenced to 11 years in prison, where he died last year – for advocating democracy. His wife remains under virtual house arrest. Also surprised will be the families of human rights lawyers recently imprisoned and of the Hong Kong bookseller kidnapped into China for selling liberal books. In Xinjiang and Tibet, grim fates await those demanding religious freedom.

Brainwashed Chinese students in the UK assure me that what happened in Tiananmen Square was a riot of “hoodlums against our army and police”. Overholt’s conclusion on 3-4 June 1989 is almost as misleading. Although he concedes that what happened in the square was “morally repugnant and gratuitously violent, the idea that it was uniquely awful is a Western ideological fiction”. Speaking as one who was there, I can’t attest that Tiananmen was uniquely awful, but what was certainly unique was that similar killings occurred that spring in well over a hundred other cities.

A lifetime of “wandering” in Asia has convinced Overholt that “transplanting Western electoral and judicial systems into the poorest countries” often just makes their situations worse. For poor countries, the path to true happiness for the most people “begins with Leninism in politics and socialism in economics”.

The book’s prime examples, besides China, are Taiwan and South Korea. If Overholt had “wandered” in Taiwan in the middle and late 1950s (when I lived there), he would have noticed that almost every Taiwanese, who made up most of the population, spoke fluent Japanese. The “miracle” that transformed Taiwan was neither Leninism nor socialist economics. In fact, Taiwan was one of the jewels of Japanese imperialism from the late 19th century to 1945. While Taiwanese initially welcomed mainland liberation – until 1947, when Chiang Kai-shek’s soldiers massacred many of them – the bedrock of the island’s success was Japanese.

I don’t know whether Deng Xiaoping, who studied Taiwan’s success, as Overholt notes, knew its history. He praises Deng, leader of the People’s Republic from 1978 until 1989, throughout his book and praises his biographer Ezra Vogel more than anyone else in his acknowledgements. For a more critical account, he should also have read Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life (2015), by Alexander V. Pantsov with Steven I. Levine, who show how, for much of Mao’s career, Deng urged him on to ever greater killing. They conclude that “Deng was a bloody dictator who along with Mao was responsible for the deaths of millions of innocent people due to the terrible social reforms and unprecedented famine”.

Overholt is also generally positive about China’s current president, Xi Jinping. But he foresees possible “bumps in the road”. China, he avers, “is on the cusp, of greatness or tragedy, and the stakes are so high that small unexpected events could make the difference. That is the defining quality of China’s crisis of success.”

I find it difficult to follow Overholt’s praise of the Asian-Chinese model. Only near the end of this book does he suggest that China might fail, while insisting throughout that the model is the best way ahead for backward countries and their peoples, who become prosperous and comfortable and want nothing better. But senior China-watcher David Shambaugh, with whom Overholt says he agrees in essence, warns that “I do not want China to collapse nor do I see this as imminent. I simply see the [Chinese Communist Party], like all Leninist systems, in a lengthy and protracted process of decline that will take years and perhaps decades before it somehow ends.”

Overholt correctly asserts that Mao and Maoism were a disaster for the Chinese (although, as I say above, he skips past Deng’s role in this). The leading historian of the Mao years, his Harvard colleague Roderick MacFarquhar, contends that for Xi it is “historical nihilism” to write off the Maoist period: “Xi fears that would ultimately mean denigrating Mao, and, as his portrait on Tiananmen demonstrates, the Chairman is still the legitimator of the regime.”

The symbolism of that huge portrait is hardly a bump.

Jonathan Mirsky was formerly associate professor of Chinese history and comparative literature at Dartmouth College.

China’s Crisis of Success

By William Overholt

Cambridge University Press, 304pp, £19.99

ISBN 9781108431996

Published 31 January 2018

The author

William H. Overholt, senior fellow at the Harvard Asia Center and Kennedy School of Government, obtained his BA from Harvard University before going on to Yale University for a master’s degree and a PhD. He has worked in thinktanks, planning projects for many US government departments; as an investment banker in Hong Kong and Singapore; and as a political adviser during periods of conflict and transition in what was then Burma, Hong Kong, the Philippines and South Korea as well as Zimbabwe.

Alongside his work in a wide variety of other sectors, Overholt has held a number of permanent and visiting positions in the academy. While based at the RAND Corporation, the well-known Californian thinktank, from 2002 to 2008 as the Asia policy distinguished research chair, for example, he also taught at both Yonsei University in South Korea and Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

The author of two books on forecasting, Political Risk (1982) and Strategic Planning and Forecasting (with William Ascher, 1983), Overholt also edited pioneering collections on Asia’s Nuclear Future (1976) and The Future of Brazil (1978). But he served as head of the Asia Policy Task Force during Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign in 1976 and is now best known as an analyst and adviser on Asia and US-Asia relations. His book The Rise of China: How Economic Reform Is Creating a New Superpower (1993) was widely criticised at the time of publication, though many now regard it as prophetic. It was followed by Asia, America and the Transformation of Geopolitics (2008) and now China’s Crisis of Success.

Matthew Reisz

后记

Print headline: Is this a road worth following?