Since the 1960s, the number of universities in the UK has trebled. The number of postgraduate degrees awarded is at least 16 times what it was in 1970, as staff and student numbers have similarly mushroomed.

About half of the 200,000 or so academic staff currently employed by British universities are teaching library-based subjects, of whom at least 30,000 might be expected to be interested in unpublished material in archives. So how is it that academic researchers are now rarer in the British Library and the UK’s National Archives than they were when I started my doctorate in 1969?

The British Library has become, in effect, an undergraduate reading room: during the run-up to exams, every seat has been taken by mid-morning. At the National Archives, the majority of researchers are doctoral students from Asian universities, older people investigating their ancestors, and so-called record agents photographing documents for hire.

It is tempting to link the disappearing academic researcher to declining academic standards. The number of first-class undergraduate degrees awarded by UK universities has more than tripled since the mid-1990s, even as nothing in the daily news suggests that the national level of intellect is rising. And while teaching standards may have improved, they can hardly explain such a dramatic increase, especially given the growth of competing pressures on academics to recruit graduate students and to produce research that can contribute to the latest research assessment decathlon.

When pressure becomes too great, something has to give way: and what seems to be giving way is scholarly integrity.

Unlike scientists, academics in humanities and social science departments are not generally tempted to falsify results: in so far as their work has any “result”, nobody much notices if they repeat somebody else’s. Rather, what seems to be happening is that processes are being falsified.

A very large proportion of the footnotes attached to academic publications in recent years have been recycled from other people’s publications. This can be seen from the way citations of archival sources are often propagated in the same incorrect form (deplored by those in charge of the archives) across publication after publication, and by absence of citation of obviously relevant foreign-language sources. Presumably, the reasoning is that since many scholarly articles and (slightly older) scholarly monographs are available online, why waste time going to an archive or library? Indeed, many universities now require doctoral students to present a complete bibliography at an early stage of their “research”, as if research consisted of writing up what they already knew, rather than pursuing ideas and historical occurrences from one source to the next.

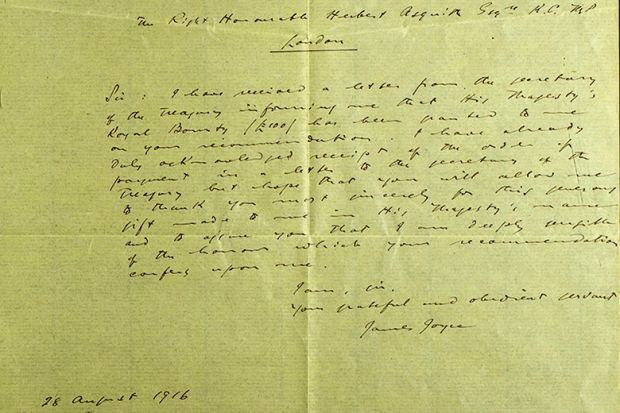

In the 1960s, many universities encouraged even first-degree students to go to original sources. After all, even a random search in the archives can unearth many hitherto unpublished documents. On a recent trip to the National Archives, for instance, I found several such texts. One was a 1916 note written by the private secretary to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith recommending a £100 grant to an “outspoken” Irish author of a book of short stories named James Joyce. “He used to drink too much when he was young but seems to have a made a very admirable recovery,” it adds. I also found a letter from Joyce thanking Asquith for the grant.

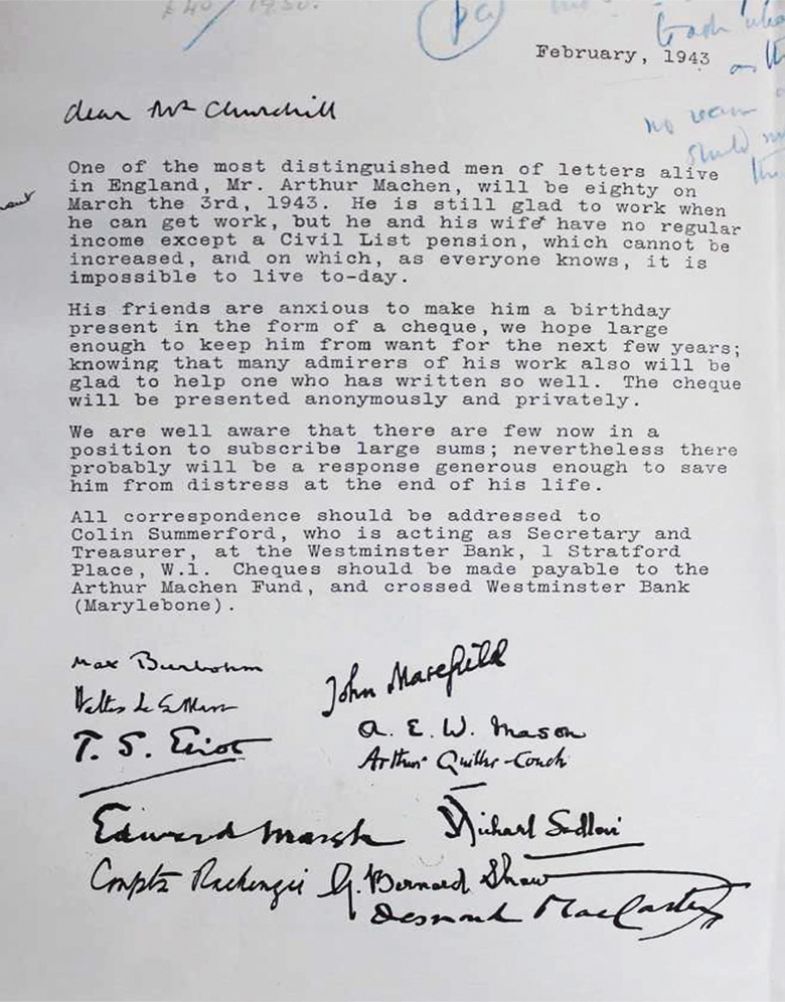

Then there is the 1943 letter to Winston Churchill (below), signed by a list of literary luminaries including T. S. Eliot and John Masefield, requesting a contribution to a fund to help alleviate the penury faced by the now largely forgotten horror writer Arthur Machen (described as “one of the most distinguished men of letters alive in England”) as he approached his 80th birthday.

These are exactly the kinds of serendipitous discoveries, not actually very significant but rather delightful, that might be turned up even by an inexperienced researcher ready to spend several days looking for what might be found, rather than checking up, in a flying visit, on what they already know. Of course, there’s always the risk of finding nothing that hasn’t been previously noticed (especially if your teacher doesn't know how to find anything either), but it used to be received wisdom that research was a risk – not so much because another researcher might beat you to it but because your project might turn out to be a case of barking up the wrong tree. Modern academics evidently feel unable to take such risks in the race to meet institutional expectations about “results”.

But what are these results? The huge increase in the amount of research being produced by academics and graduate students might conceivably correspond to an equally impressive increase since the 1960s in the quantity of outstanding, groundbreaking research in the humanities and social sciences. But if you believe that, you probably believe that the next phase of lunar exploration is going to lead to huge reductions in the price of cheese.

Arnold Harvey is a historian, writer and academic who has taught at the universities of Cambridge, Leipzig and Salerno.