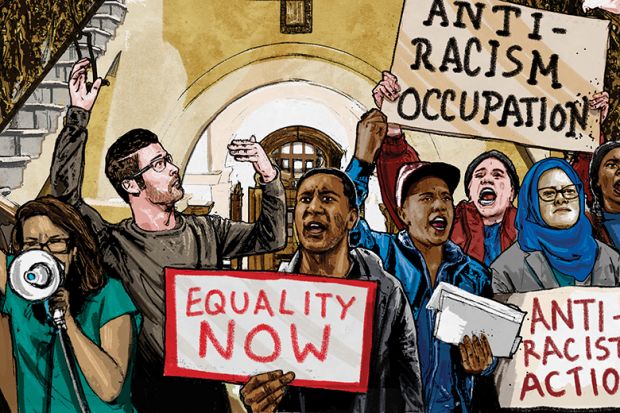

Student activists at Goldsmiths, University of London have today reached their 100th day of occupying a prominent building on the university’s south-east London campus.

Their manifesto expresses a simple wish: the right to study without fearing abuse or unfair treatment. And far from being an isolated cause, the actions of Goldsmiths Anti-Racist Action echo the worldwide call to fight racism within institutions and to decolonise universities.

Following the 2015 events at the University of Cape Town, inscribed in the collective memory as “Rhodes Must Fall”, several universities and colleges in the UK undertook a review of their curricula. These include SOAS University of London and the universities of Leeds, Birmingham and Oxford. More recently, the University of Cambridge launched an inquiry to study how it profited from colonial slavery.

However, four years after the statue of Cecil Rhodes was removed from Cape Town’s campus, little seems to have changed. Students should not have to come to a point where occupying a campus is the only way to see their rights respected. Is it really so difficult for senior academics and staff to recognise the challenges and trauma that students of colour face in their daily lives?

These movements also force me to ask myself a more personal and uncomfortable question: as a white academic, how should I contribute to the debate on race? Willingly or not, being a white male puts me somewhere on the pyramid of white supremacy. Even though my parents are Polish working-class migrants, I was born into the privilege of not being immediately identifiable by the white social mainstream as “other”. And when I entered academia, I became an agent of a global institution with a tradition of othering, erasing cultures and history through the power of language. I feel the obligation to use the power I have for justice; the question is how.

My own observations and experience suggest to me that there is an urgent need for the actions and attitudes of university staff and scholars from all disciplines to be more closely informed by real-life experiences. There is a difference between reading scholarly accounts of racism and actually experiencing it. And research shows that privilege blinds people to oppression and dampens their ability to be empathetic. Empathy starts with reading situations through the lens of vulnerability, acknowledging that others experience trauma, and knowing how to respond.

At the same time, it is not the victims’ burden to educate on questions of race. Rather, it requires a critical act of self-reflection: how would we like someone to respond if we were grieving or if we had been abused?

Second, it is imperative for universities to produce research with non-white communities, instead of doing research on them. Communities need to be considered as stakeholders rather than curiosities to be put under the microscope. This also means reconceiving universities as facilitators of knowledge rather than producers. It is not enough to point out the limitations of Eurocentric theories and to include indigenous concepts, scholars and literature in research proposals or the curriculum. It is about building bridges.

The public has a right to ask academics for practical solutions to their problems, and to be consulted for feedback in a two-way process. Academia should feel indebted to the subjects it studies, and facilitate access to the knowledge, publications and books it produces out of them.

Moreover, since academics are generally more likely to be listened to in the public sphere than are the marginalised communities they study, it is a duty for scholars to use that power to challenge harmful narratives and restore the truth in spaces the general public cannot access, whether it is on an international or local level.

Ultimately, there is a need to collectively distance ourselves from whiteness as a system of exclusion. White people should not feel defensive when hearing the word “whiteness”; instead, they should understand that it is a deeply embedded structure that affects every part of the society. This means actively disengaging from certain discourses, taking marginal voices into account and standing up for those being unfairly treated. Speaking truth to power is costly, and it is understandable that most would baulk at the idea of risking jobs, money, time, energy and their well-being. However, remaining silent can be even more costly and can lead to disastrous consequences.

Some academics might feel that, although necessary, disengaging from whiteness is alienating. But I argue that it is an opportunity for reflecting on our intentions: why are we in academia in the first place? What is our job really about? Is it about following trends to secure ourselves a comfortable life? Or is it about using the resources and the access to students that we enjoy to actively foster a better world?

The need to create more inclusive universities follows a simple law of society: for institutions to flourish, it is necessary that all parties involved flourish. This can be achieved by asking a few key questions. Are our current decisions spreading harmony or chaos? And ultimately, what contribution do we want to leave behind?

William Barylo is a British Academy research fellow in the department of sociology at the University of Warwick.

后记

Print headline: All shades of caring

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?