A common refrain in modern research is the need to increase collaboration, whether that is internally within a university, between academics in different countries or reaching across disparate disciplines.

It has inevitably led to a growing amount of research being authored by more than one academic, and in some cases publications can list hundreds of scholars as co-creators. But does this mean that single authorship in research is dying out, and is this potentially a problem?

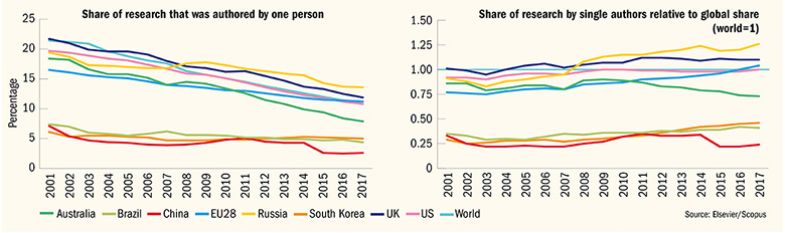

Looking at the data on the prevalence of single-author papers across all disciplines confirms its continuing decline since the beginning of the century. Across the world, single-author publications made up 21.4 per cent of articles, reviews and conference papers indexed in Elsevier’s Scopus database in 2001, a share that had almost halved by 2017 to 10.8 per cent.

However, the rate of this decline has been variable across different nations. While countries such as the UK and the US have generally followed the world trend, others already had a relatively low proportion of research produced by single authors.

The shrinking share of solo-authored papers

The share of single-author papers in China, Brazil and South Korea, for instance, was below 8 per cent in 2001. In China, this share has kept falling, to represent a mere 2.6 per cent in 2017. In Brazil, too, it has dropped, although not as rapidly, with 4.4 per cent of papers being by single authors in 2017. In South Korea, the proportion of single authors seems to have bottomed out at about 5 per cent.

Such variations can be seen more clearly by examining how nations have changed relative to the global average. A striking contrast is presented by Russia and Australia, which in 2001 had a similar share of overall research produced by single authors. By 2017, however, they were a long way apart, with Australia below the world figure, at 7.9 per cent, and Russia above, at 13.6 per cent.

So what are the potential drivers in such variation?

Vincent Larivière, professor of information science at the University of Montreal, said the disciplinary mix of research in each country was likely to be a “strong component”.

“We know that researchers in the social sciences and humanities are more likely to publish alone than [those] in the sciences,” he said, adding that countries such as China had a higher proportion of science papers indexed in bibliometric databases.

A flavour of the disciplinary variations can be seen in Scopus by looking at the global share of single-authored papers in different fields: in 2017, solo authors accounted for some 78 per cent of publications in history, compared with 28.1 per cent in economics and econometrics. In organic chemistry, the worldwide figure was 2.4 per cent.

Professor Larivière said the national variations could also be down to other factors, such as different cultures of collaboration, but without detailed analysis controlling for variations in each subject it would be difficult to know the extent of this.

However, he added that the overall global decline in single authorship may have been impacted by a shift towards crediting authors who might not have been named on papers in the past.

“I do believe that authorship criteria may also affect the trends, where those who have made more technical contributions will now be authors, while it was not the case before,” Professor Larivière said.

Giulio Marini, a research associate at the UCL Institute of Education, said the overall shift towards “bigger” science, the structure of funding systems and the knock-on effect of research assessment were also likely contributors to the decline of single authorship. This last factor arguably had led to “contrived co-authorship” – the practice of listing authors who have contributed little to a project, in some circumstances because of the need for academics to demonstrate productivity.

“All these reasons may explain why some people may frown [in] the wake of a single-authored publication. To some…it is a sort of wasted opportunity to establish connections and boost productivity,” he said.

One way to shore up single authorship might be to tackle the problem of contrived co-authorship by more accurately measuring research contributions in multi-authored papers. “Generally this normalisation, or ‘fractioning’, to account for actual productivity does not exist in many national systems,” Dr Marini said.

However, without such changes, could we see single-authored papers disappear entirely in some disciplines? And might there be sound reasons for still encouraging researchers to produce them?

Jos Barlow, professor of conservation science at Lancaster University, and co-author of a 2017 editorial on the topic in the Journal of Applied Ecology, said single-author papers should “be neither encouraged nor discouraged – the science should be judged on its quality, irrespective of who the authors are, where they are from, or how many there are”.

However, he added, in a “world where science is increasingly multidisciplinary, with each paper building on a wide range of knowledge, skills and techniques, then it is harder for single authors to compete”.

That said, data presented in the editorial suggested that the rate of decline in single-author papers in applied ecology had slowed over the years as the proportion got closer to zero. Does this imply that there will always be some place for single authorship, no matter the discipline?

Professor Larivière pointed out that “single authorship remains present, even in the most collaborative disciplines”, and for solid reasons, which suggests that we should not write it off entirely just yet.

“Theoretical contributions, for instance, remain more often the results of single individuals, and unless scientists stop theorising, there will always be single-authored papers,” he said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

后记

Print headline: Last ride of research’s lone rangers?