An extraordinary amount of ink has been spilled in Canada over the value of university degrees. That value is almost always defined in economic terms and assessed according to individuals’ earnings soon after graduation. Popular wisdom has it that many graduates – especially those in the humanities, social sciences and the arts – are stuck in minimum-wage jobs as baristas.

But all existing measures of graduate earnings have serious shortcomings, likely leading to poor university choices and the misallocation of human talent. To help fill this information gap, our Education Policy Research Initiative (EPRI) teamed up with Statistics Canada and 14 post-secondary education (PSE) institutions from across the country to link administrative data on students held by the PSE institutions to tax records.

We then tracked labour market outcomes of graduates on a year-by-year basis for each graduating cohort from 2005 to 2013. Hence, uniquely, we were able to identify initial earnings, increases over time and cross-cohort patterns, all of which matter.

The full set of findings can be viewed at www.epri.ca/tax-linkage. We focus here on the main results for bachelor’s graduates, but we analysed community college graduates, too.

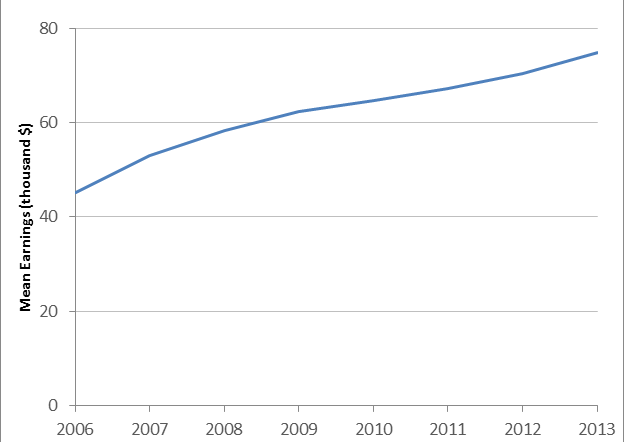

It turns out that degree holders have been faring rather well. For all 2005 bachelor’s graduates, average annual earnings were C$45,200 (£27,400) in 2006. Their earnings then grew steadily, increasing by an average of C$4,200 a year in 2014 terms, to reach C$75,000 eight years after graduation: a 66 per cent rise.

Figure 1 – Mean earnings of all degree graduates, 2005 graduation cohort

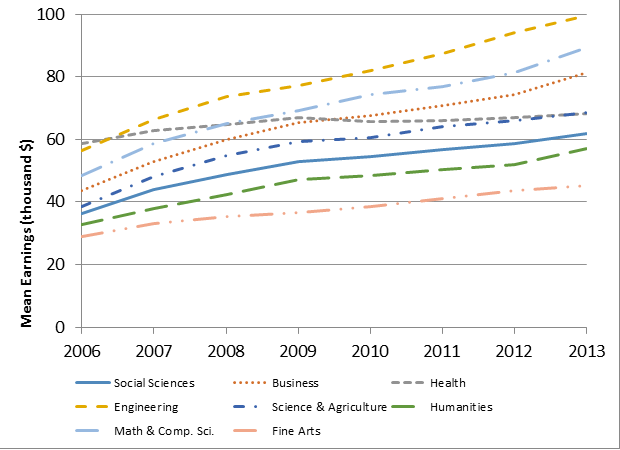

Similar outcomes hold for other cohorts, debunking the popular fallacy that university graduates are not doing well in the labour market. That said, starting salaries and earnings growth vary substantially across fields. At the top end, engineering graduates began their careers earning about C$60,000, rising to C$100,000 seven years later. Next on the earnings scale were graduates in mathematics and computer science, followed by those in business and science/agriculture.

Graduates in the visual and performing arts had the lowest average earnings, but their figures should also be seen in context. While it is not easy to come up with a good estimate of what baristas make (or how many university graduates are working as baristas), a reasonable approximation might be in the C$12 an hour range (near the prevailing minimum wage across Canada). If we assume that they work full-time all year (very steady work), that yields an annual salary of C$22,150. By contrast, the average graduate in the visual and performing arts earned C$28,800 right after graduation, and $45,100 within eight years. Graduates in humanities and the social sciences were earning even more by then: in the range of C$60,000.

Figure 2 – Mean earnings by field of study, 2005 graduation cohort

It is important to note that these data include all graduates who earned more than C$1,000 a year, as long as they were not continuing their studies. So the averages include those working part-time and part-year. Furthermore, those who do continue to postgraduate studies or professional degrees, including MBAs, law, medicine, dentistry, generally have high earnings potential, so any averages that included them would be even higher.

Work on PSE-tax linked data continues. Statistics Canada is building files of this type for all graduates from all PSE institutions on a province-by-province basis. Work is also beginning to link post-graduation earnings to the wide range of student characteristics and schooling experiences captured in these PSE-tax linked files – which can be augmented with additional data held by PSE institutions on a project-by-project basis.

Such work should be able to tell us not only what graduates earn, but help us to understand what factors lead to higher earnings levels. This will help decision-makers at all levels: students, their parents, PSE institutions and policymakers across a range of ministries.

Ross Finnie is director of the Education Policy Research Initiative and a professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. Richard E. Mueller is associate director of EPRI and professor of economics at the University of Lethbridge. Arthur Sweetman is associate director of EPRI and professor of economics at McMaster University.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?