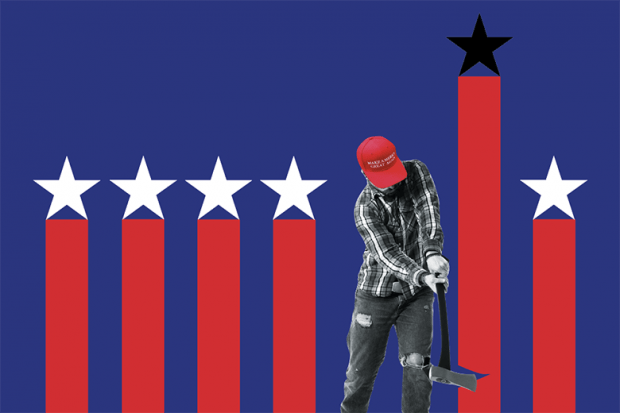

With Donald Trump bidding to return to the White House, and the interventionism of conservative lawmakers evident in recent congressional hearings, US higher education finds itself in an uncomfortable spot.

In an era in which “go woke, go broke” is a unifying mantra for the political right, universities’ embrace of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) is a particular flashpoint.

They are not alone in that. One prominent subplot of the attempted assassination of Trump at a rally in Pennsylvania was the scrutiny of the Secret Service for failing to prevent the attack, during which many commentators focused on the security detail’s female agents.

The accusation was that this equated to a lower level of competence than an all-male team, and that DEI had been put above the security of a past – and perhaps future – president.

It was a reminder, if one were needed, that DEI is a red rag to the political right wherever it is found, and in our cover story this week we assess what this means for US colleges.

Among the proponents we speak to is Anthony Abraham Jack, an associate professor of higher education leadership at Boston University, who once struggled to make ends meet as a student with high grades but without the family wealth to subsidise his inadequate student aid.

For Jack, who is black, institutions that invest in DEI do so in the knowledge that even well-meaning institutions can perpetuate the problem if they are not actively working to combat it.

Left unexamined, he says, “university policies, almost invisibly, disadvantage the most disenfranchised students”.

However, this view – and efforts by many universities and colleges to act on it – is under sustained assault, and in a number of Republican-controlled states public institutions are disinvesting from DEI programmes following legislation restricting such activities.

One opponent explains the objection in stark terms: “Equity is reverse discrimination.”

The idea that universities need to be dragged away from excessively “woke” tendencies is now commonplace in the UK too, with the last Conservative universities minister launching a review into “woke science” that continues its work.

Part of the problem, perhaps, is that the concept of DEI – or equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in a UK context – has become too many different things to too many people, with the result that we have lost our grip on what it should mean, and who, how and why it is seeking to help.

Such issues are best brought to life, as David Lammy – now the UK’s foreign secretary – did when speaking about the need to improve university access at a Times Higher Education event in 2019.

Lammy told a story about one of his own constituents in north London, a high-achieving teenager of Ghanaian descent.

“Everyone in the community thought this girl was outstanding,” he said. “Everyone in the Ghanaian African community in London expected her to go to Oxford. She gets the interview. Half the family go to Oxford with her. She has the interview. She doesn’t get in.

“The tutor communicates: ‘Look, you were good, you were strong, but we felt that if you needed to bring your whole family with you, would you really fit into this environment?’”

Efforts to help those representing the status quo to better empathise with individuals from different backgrounds is the sort of thing that few should object to.

So given the irretrievable polarisation of concepts such as “wokeism”, there is perhaps merit in talking less about a catch-all idea of DEI/EDI, and instead breaking it down into its constituent parts, which can be assessed with greater nuance.

The political winds are blowing in opposite directions on either side of the Atlantic at present.

In the US, higher education has the prospect of a vice-president in J. D. Vance – Trump’s running mate – who has said that “the professors are the enemy”.

In the UK, the Labour insider Lord Mandelson told THE in a recent interview that while he believed higher education needs reform, “you reform on the basis of a commitment to universities and what they do in and for our country, not on the basis that you want to destroy them”.

Two very different approaches. As our cover story makes clear, two similarly divergent views are driving the debate about DEI: is it giving unfair advantage, or redressing unfair disadvantage?

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?