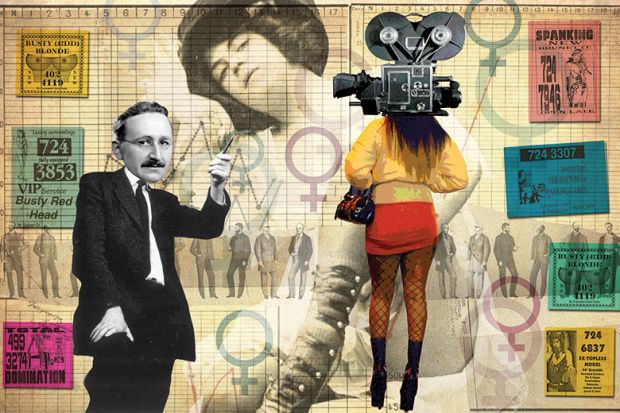

Sex sells. That seems to be the conclusion of Playboy magazine, which, in February, announced that it was reinstating nude photos. According to Cooper Hefner, its new chief creative officer, last year’s decision to remove nudity “was a mistake”.

It’s a move that is hotly debated among feminists, who could not be more divided on the question of whether the sex trade is good or bad for women. But it is also a move that deserves attention from economists.

The pornography industry has been estimated to generate more revenue than Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Yahoo, eBay, Netflix and Apple combined. It has also been expanding, alongside facing significant disruption from changing technology and greater competition. It has the makings of a textbook case study for any serious economics student. However, it is territory that currently receives serious attention only from gender studies.

This is both ironic and destructive. As Alex Marshall pointed out in his 2014 book The Surprising Design of Market Economies, for markets to work well, they require the support of the state to maintain the necessary conditions, such as law and order and infrastructure. Collectively, we pay taxes to fund such things, and to be provided with the social security that allows us to mitigate the risks of relying on market incomes and maintain a reasonable standard of living through periods of poor health, unemployment, parenthood or old age.

Search for academic jobs in business and economics

Economists are obsessed with markets, and women’s bodies have been bought and sold for time immemorial. Yet the sex trade has for too long been left to operate with virtually no official support or recognition. And sex workers have therefore been left vulnerable to exploitation, not just from pimps and clients, but also from the authorities.

The usual justification for brushing the sex trade under the carpet is that the sale of sex is “immoral” and that it preys on the most vulnerable in society. In the words of Kat Banyard, author of the 2016 book Pimp State: Sex, Money and the Future of Equality, “some trades are too toxic to tolerate…A society that acts in law and language as if men who pay to sexually access women are simply consumers, legitimately availing workers of their services, is a society in deep denial about sexual abuse – and the inequality underpinning it.”

However, there is a logical inconsistency with the way that we think about consensual prostitution – a largely female trade – compared with the male-dominated spheres of soldiering and boxing – all of which come at significant risk to the body and the brain. As Barbara Einhorn, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Sussex, wrote in a 2016 letter to The Guardian, “prostitution and soldiering are arguably the oldest professions. While doubts about their legitimacy are understandable, both provide a service that society appears to need. Yet one is heroised, the other vilified.”

As a society, we are also, funnily enough, completely comfortable with people in effect pimping their brains. If you have high-level numerical or literacy skills, it is fine to work long hours, for example, at a multinational bank or law firm. But if you’re born with a great body and are able to hone your erotic skills, it is seen as animalistic and shameful to make money from those “assets”.

The reason is that a woman’s value is traditionally associated with sexual virtue rather than brainpower. Throughout history, prostitutes have been depicted as a threat to both male sexual control and the sexual virtue of other women. That is why medieval prostitutes had to mark themselves out with striped hoods, and why female nudes in art adopted unthreatening poses, such as looking away from the viewer. And since women have traditionally been seen as inferior, it has been assumed that making money from the female-associated body is less respectable than making it from the male-associated brain.

Now, for society to be inconsistent is one thing. For supposedly rational economists to be likewise is another. As a profession, we economists need to be standing up to irrational societal norms. The inconsistent treatment of a largely female profession compared with largely male professions is nothing other than sexism under the cover of “well-meaning” paternalism. Those engaging in consensual sex work need to be helped to benefit from markets that work with them rather than against them. And economists are best placed to recognise that and fight for change.

They have a lot of work to do. Despite Amnesty International’s declaration of support last year for the decriminalisation of consensual prostitution, the issue remains highly contentious. The Nordic model, under which the buying rather than the selling of sex is criminalised, is becoming increasingly popular. But shifting the criminal blame to the buyer arguably leaves the prostitutes no less exposed, their profession no less socially scorned.

The neglect of the sex trade is an eloquent symbol of fact that women are seriously under-represented among economists. But it cannot go on. However dismal your view of prostitution as a career, there is no question that this oldest of trades is a topic ripe for study by the dismal science.

Victoria Bateman is fellow and director of studies in economics, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Time for economics to embrace the oldest market – the sex trade

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?