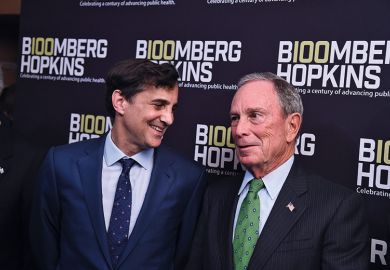

In an unprecedented move late last year, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg donated $1.8 billion (£1.4 billion) to his alma mater, Johns Hopkins University. His aim was to ensure that “finances will never again factor into decisions” about admissions, and to “make the campus more socio-economically diverse”.

However laudable Bloomberg’s goals may have been, though, it is crucial for America’s education leaders – and its philanthropists – to remember that financial aid is only the first step in ending inequality on campus. They must also keep in mind what students need to be full members of the community once they arrive on campus.

Just one week after Bloomberg’s announcement, for instance, Johns Hopkins’ policy to close its dining halls during the Thanksgiving break forced some of its most disadvantaged undergraduates to confront a reality common across US campuses: food insecurity. The assumption that all students depart for family reunions around a turkey dinner during Thanksgiving – or for fun in the sun during spring break – condemns those who can’t afford to travel (as well as those with troubled familial relationships) to go hungry for days on end.

I met many such people during my five years of research for a book, The Privileged Poor, on the hurdles that poor students face. For instance, Nicole (not her real name), a driven scholarship student with a distinctive laugh, lamented that administrators at her college “don’t understand what it means to be here…not being able to go home, not having money to eat. [In my] freshman year, I literally had no money.”

I ran into Nicole during spring break. She was carrying six plastic bags, loaded with everything from sandwich meat to cans of beans. She looked tired and, as she set down the bags and shook her hands to regain feeling, I noticed the ridges they had dug into her fingers. She bemoaned how all the stores close to campus were too expensive for her budget: “One of the reasons a lot of the students aren’t going home is because of money and you’re just making us spend money to stay here!”

Nicole was fortunate to be able to buy enough food to last her through break. Others were not. Many students rationed food that they stole from their closed cafeteria (often with the help of sympathetic service workers) or cut back to one meal a day.

Tracey, a low-income Latina with a passion for social justice, did both. As she was fearful of her abusive father and of neighbourhood dangers, leaving campus for spring break was not an option. She took on additional shifts at her job but still had to keep to a single meal a day – which often came from the vending machine. Towards the end of break, while alone in her room, Tracey found herself on the floor, not knowing how she got there. She had fainted.

Poor students get a particularly raw deal at colleges that charge students to stay on campus during breaks (while still not providing food). At St Lawrence University in upstate New York, for instance, the fee for this in 2019 is $160. When your only source of income is a work-study job, this is a lot, especially for the many lower-income students who are also supporting family members back home.

Food insecurity is finally receiving attention as first-generation and lower-income students begin to speak up. This has stimulated efforts to document how widespread the problem is. In October, sociologist Sara Goldrick-Rab and the Hope Center at Temple University published a report showing that roughly two-fifths of US undergraduates endure low food security. And, in December, the Government Accountability Office published the first official report on the issue. While national estimates of its extent and impact are still unavailable, there is clear consensus that food insecurity undermines academic performance and persistence – let alone physical and emotional well-being.

I have successfully lobbied Harvard University and other institutions to keep vital services available during breaks. However, at community and less-resourced colleges, food insecurity is rarely confined to breaks. Consequently, we need additional measures, such as opening on-campus food pantries and food banks, and apps that alert students to campus events with free meals. There is also a push for professors to adopt “basic needs” statements on their syllabuses, informing students of where to turn in times of need.

But even these solutions do not fully address how systemic inequalities run rampant on our campuses. Higher education institutions as a body must lobby government to make more resources available to those striving to achieve the American dream. Increasing the size of Pell grants would be a start. Another important step would be to make students eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which helps poor Americans to afford food.

Poverty is pernicious. It undermines even the most valiant attempts at upward mobility. As universities recruit increasingly diverse classes, they must understand what it means to support those students. Moreover, they must do something with that knowledge.

Anthony Abraham Jack is the author of The Privileged Poor and an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?