It has been a great month for Irish women. Mary Mitchell O’Connor, the higher education minister, announced a “radical” measure aimed at addressing the large gender imbalance at the top of the country’s higher education system. This initiative, which follows the lead set by the likes of the University of Melbourne and the Max Planck Institute, would see 45 “female-only” professorships created over three years, pushing the proportion of women in such positions closer to the goal of 40 per cent.

There has also been some belated buzz about a gender strategy report released in August by the Irish Research Council (IRC), the Republic of Ireland’s primary funder of PhD and postdoctoral fellowships. The report stated that the introduction of gender-blind assessment “resulted in a significant improvement in the representation of female researchers across disciplines”. One statistic is truly remarkable: the percentage of postdoctoral awards in science, technology, engineering and mathematics increased from 35 per cent before gender-blinding began in 2014 to 57 per cent in 2017.

Viewed through a different lens, however, it has been a terrible month for Irish women. Critics of “female-only” professorships predictably wrung their hands over the possibility of lower standards if promotions are denied to deserving men so that they can be gifted to less-deserving women. Some announced that the measure insulted women by implying that they could not secure senior positions on their own merits.

But the IRC data shine a floodlight on the remarkable extent to which biases disadvantage women. Coming just days after a woman’s lacy underwear was cited in defence of the accused in a rape trial, this discourse has delivered to Irish women a sharp reminder of the double standards and hurdles that remain to be overcome in the slog toward equality.

It is frequently asserted that, proportionally, as many female academics as male academics are appointed, promoted or awarded grants; but women make many fewer applications. According to Mark Ferguson, director general of Ireland’s main science funder, Science Foundation Ireland (which has granted seven times as much funding to men as to women), women ask themselves “is this the job for me now?” while men have a more “go-for-it attitude”.

This narrative, which places the blame on women themselves, holds considerable sway. After all, there is evidence that even women who work full-time bear the lion’s share of the physical and mental household work, so it makes sense that they are more reluctant to step up to roles carrying additional responsibilities and demands. But this argument is just another manifestation of the profound, pernicious and ubiquitous gender biases that take hold so early in life that their influence on men’s and women’s capacities and preferences is completely inseparable from any biological differences. When six-year-old girls endorse gender stereotypes about the supposed greater incidence of male brilliance – and endure a lifetime of being judged more harshly than their male peers – is it any wonder that they are less willing to subject themselves to the application processes for promotions or prestigious grants?

The IRC data only add to a growing body of evidence that, when their gender is removed from the equation, women are judged much more favourably in a whole range of settings, from journal publication and selection of conference papers to orchestra auditions. It suggests that gender-blinding should be taken very seriously by any body claiming commitment to equality of opportunity for women.

At the very least, public funding agencies and hiring institutions should be required to release data on both successful and unsuccessful applicants across all mechanisms and levels of appointment, as well as on the gender composition of review panels. Such data are incredibly difficult to come by, but transparency might expose and correct systemic bias, such as the egregious history of gender bias in promotion at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

When people object to these measures on the grounds that we should not need them, I agree wholeheartedly. But the fact is that we do. Human brains like shortcuts, so biases – conscious and unconscious – are not easily altered. If male-only professorships were proposed, would anyone fret about lowered standards? I suspect not.

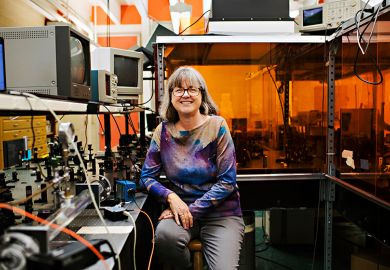

We have abundant evidence that there are amply qualified women in junior positions. To take a stark example, one of this year’s Noble laureates, Donna Strickland, was only an associate rather than a full professor at Canada’s University of Waterloo (she says that she never saw the point of applying for promotion). Besides, concerns about standards could easily be solved by stipulating that if no one suitably qualified applies, posts should be re-advertised.

We are told that female-only professorships will increase the visibility of women at this level and help to dispel biases by cementing the normality of female success in academia. Until that is achieved, however, top-down initiatives will still be required to compensate for our lazy brains. We need mentoring programmes for female academics that encourage and support applications for funding and for promotion. And an onus should be put on heads of schools to identify and propose suitable female candidates.

Ultimately, however, change must begin at home. Each of us has a responsibility to reflect on our own potential for perpetuating bias in how we assess and talk about ourselves and others. How we talk to children is particularly important. Until six-year-old girls learn that they truly are just as brilliant as their male peers, achieving equality of opportunity is never going to be child’s play.

Clare Kelly is Ussher assistant professor of functional neuroimaging at Trinity College Dublin and adjunct assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at New York University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Fairness is still far away

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?