H. G. Wells’ warning that civilisation is a “race between education and catastrophe” has never been more pertinent.

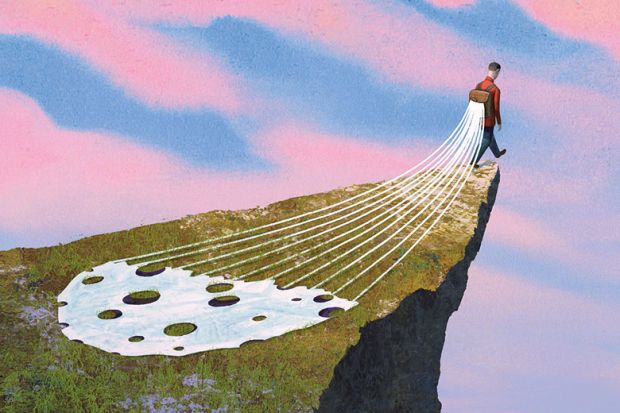

To evade the environmental, political and biomedical abyss opening up before us, young people must acquire a genuine understanding of human needs. They need a spirit of enterprise and innovation, the moral strength and resilience to respond to fast-changing situations and, above all, the empathy, determination and communication skills to work collaboratively.

The traditional emphasis on the acquisition, retention and testing of knowledge is no way to promote such imagination and creativity. Yet it is the approach to which so many still cling. In England, this is one consequence of the education system’s most fundamental flaw: its absurd reverence for academic achievement above all other forms of human prowess.

This conviction feeds an assumption that a school’s primary duty is the early identification of an academic elite, to be groomed in the scholarly way of life. Each stage of the system is designed not as an opportunity to respond to the needs of a particular age group, but as a specific preparation for the next stage. General education is sacrificed in favour of specialisation, and pupils who struggle with the academic approach are made to feel failures. Nor will this be altered by the government’s recent announcement of technically focused “T levels”, whatever the rhetoric around parity of esteem with A levels.

Meanwhile, at university, even vocational courses, such as law and medicine, have traditionally been determinedly academic in their approach. There are the beginnings of a change of approach in this respect, but reform is proving slow and painful.

In 2013, the increasingly powerful Russell Group established an academic board to advise the UK examinations watchdog, Ofqual, on the content of A levels. Michael Gove, then secretary of state for education, quickly assigned it a role that was more directive than advisory, explaining that “by placing responsibility for the content of A levels in the hands of university academics, we hope that these new exams will be more rigorous and will provide students with the skills and knowledge needed for progression to undergraduate study”.

Buffeted by awkward questions about its members’ paucity of students from underprivileged backgrounds, the Russell Group began constantly stressing the importance of taking the traditional academic A levels – English, maths, separate sciences, languages, history and geography – from which “facilitating subjects”, it said, students from non-traditional backgrounds – and the schools they attend – too often shied away.

As part of this drive to increase sixth-forms’ already heavy emphasis on the grammar school curriculum of the mid-20th century, some Russell Group members have even sent schools lists of those “soft subjects” (Gove’s contemptuous term) that are best avoided by their applicants. Marketing material is careful to avoid explicitly stating that students should not take any such subject, but the basic message is clear, and the tactic has been extremely successful. Figures show a marked increase in recent years in the number of A-level candidates studying traditional academic courses – with, of course, a corresponding decline in those subjects on the blacklist.

This is not the only unfortunate effect of the Russell Group agenda on schools. Even primary schools have begun separating their curricula into separate, specialised subjects, and a former education minister, Lord Adonis, believes that it would be appropriate for primary teachers to be academically qualified to PhD level. Meanwhile, in 2013, leading sixth-form colleges formed their own version of the Russell Group, known as the Maple Group, whose members seek to cream off academic students from a wide area with a view to grooming them for the prestigious research-based universities.

A climate has been created in the English education system in which innovation is stifled instead of encouraged. Any initiative that smacks of “progressive thinking” attracts political abuse, and school inspectors are instructed to come down hard on teachers who stray far from formal methods of instruction. Vocational and practical courses, and degree programmes that cross traditional subject boundaries, are constantly battling the stigma of inferiority. And the excellent work done by the newer universities to give undergraduates a more interesting and relevant learning experience has not received the recognition it deserves; these institutions have reportedly been dismissed by one minister in the Department for Education as “rubbish universities”.

There are still educationalists at all levels of the education system who refuse to be cowed by the bully boys, and who remain committed to good education practice. But they need more support. There is widespread awareness of what has gone wrong with the education process, but too many critics are inclined to shrug their shoulders and tamely assume that there is nothing they can do about it. If it’s essential for the Russell Group to have control of the entire system, then its members should at least wield that power with greater enlightenment than they have shown so far.

Eric Macfarlane has worked in four very different universities, promoting the recommendations of the 1997 Dearing report. Earlier in his career, he taught in and led both secondary modern and grammar schools. He was founding principal of Queen Mary’s Sixth-Form College, one of Hampshire’s pioneering open-access 16-to-18 colleges. His latest book, Who Cares About Education?, is published by New Generation Publishing.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login